2 Decision making basics

After successful completion of the module, students are able to:

- Make decisions with a great awareness of the nature of the decision and the purpose of making a decision.

- Explain the trade-offs that should be taken into account when making a decision.

- Explain different characteristics of decisions.

- Take advantage of various decision making strategies.

- Explain the rational model of decision making and the concept of the homo economicus.

- Explain the bounded rationality of humans and its implications on their ability to make decisions.

- Apply heuristics to make good decisions.

2.1 Exercises to reflect on how we make decisions

Exercise 2.2 Solve the puzzles

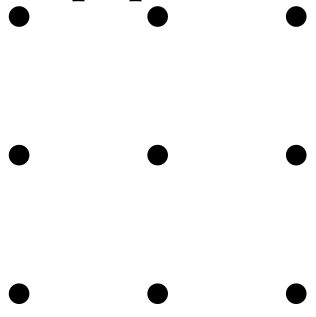

- The nine dots problem Connect the dots shown in fugure 2.2 with no more than 4 straight lines without lifting your hand from the paper.

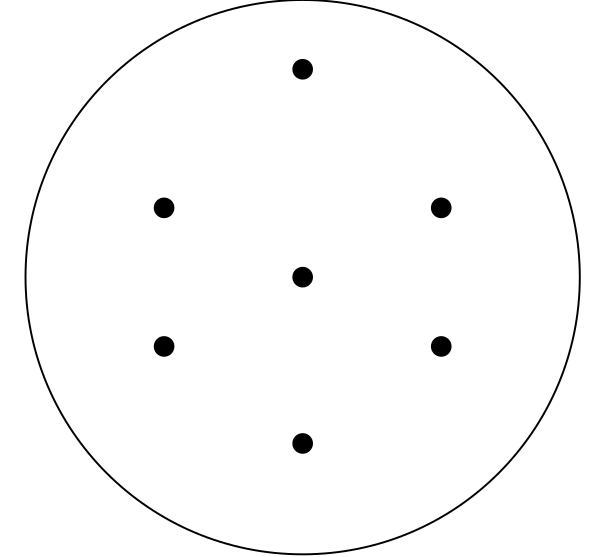

- The tasty cake puzzle In figure 2.3 you see a tasty cake with the nine dots representing strawberries. Cut this cake up with exactly four straight cuts so that each portion of the cake contains just one strawberry on the top.

Reflect on how you tried to solve the puzzles. Did you have a problem solving strategy? How did you come to the right decision? Think of restrictions you imposed on yourself which was not inherent to the problem.

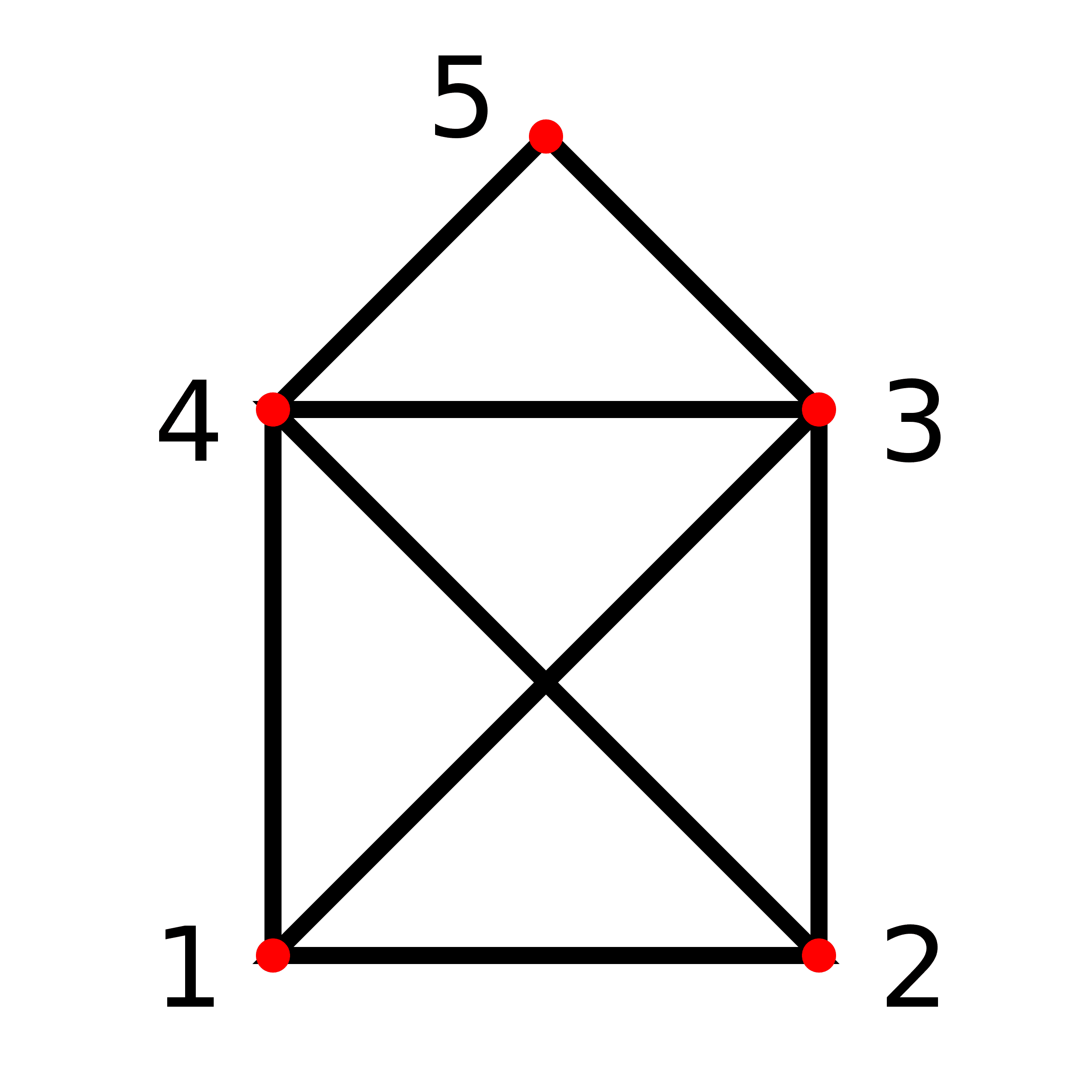

Exercise 2.3 What is the house of Santa Claus?

The house of Santa Claus is an old German drawing game. It goes like this: You have to draw a house in one line where you (a) must start at bottom left (point 1), (b) you are not allowed to lift your pencil while drawing and (c) it is forbidden to repeat a line. During drawing you say: ``Das ist das Haus des Nikolaus’’. What do you think is the success-rate of kids who play this game for the first time?

Answer the question here: https://pingo.coactum.de/ Code: 666528

Please find solution to the exercise in the appendix

2.2 What defines a decision?

The statement of Eilon (1969) still holds true:

“An examination of the literature reveals the somewhat perplexing fact that most books on management and decision theory do not contain a specific definition of what is meant by a decision. One can find detailed descriptions of decision trees, discussions of game theory and analyses of various statistical treatments of payoffs matrices under conditions of uncertainty, but the definition of the decision activity itself is often taken for granted and is associated with making a choice between alternative courses of action.”

The word decision stems from the latin verb decidere which can have different meanings5 including make explicit, put an end to, bring to conclusion, settle/decide/agree (on), die, end up, fail, fall in ruin, fall/drop/hang/flow down/off/over, sink/drop, cut/notch/carve to delineate, detach, cut off/out/down, fell, flog thoroughly.

Wikipedia defines decision making as follows:

“In psychology, decision-making […] is regarded as the cognitive process resulting in the selection of a belief or a course of action among several alternative possibilities. Decision-making is the process of identifying and choosing alternatives based on the values, preferences and beliefs of the decision-maker. Every decision-making process produces a final choice, which may or may not prompt action. […] Decision-making can be regarded as a problem-solving activity yielding a solution deemed to be optimal, or at least satisfactory. It is therefore a process which can be more or less rational or irrational…”

Businessdictionary.com defines a decision as

“A choice made between alternative courses of action in a situation of uncertainty.”

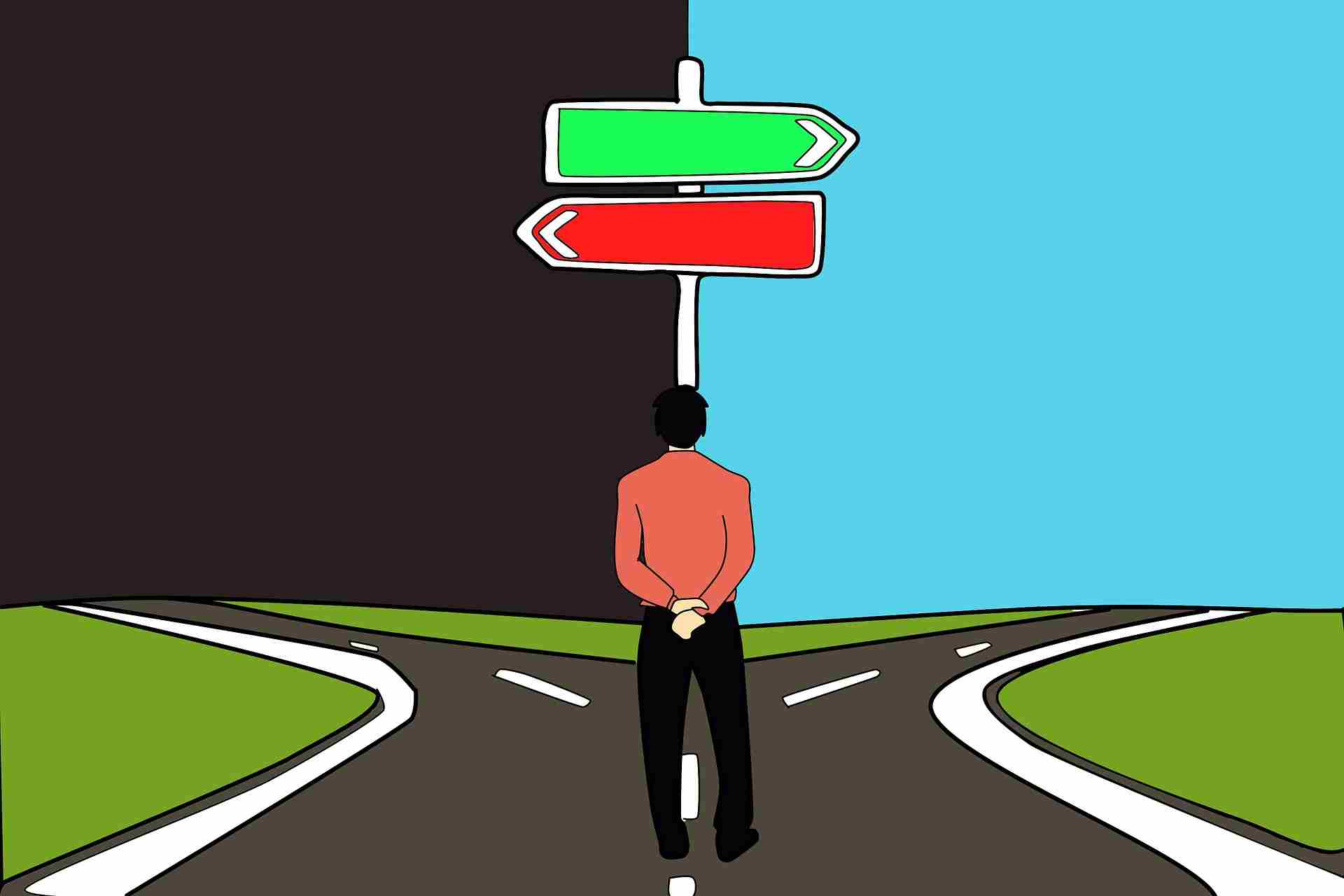

Let’s agree on the following working definition that is symbolized in figure 2.6:

A decision is the point at which a choice is made between alternative—and usually competing—options. As such, it may be seen as a stepping-off point—the moment at which a commitment is made to one course of action to the exclusion of others. (Fitzgerald, 2002, p. 8)

2.3 Types of decisions

Decision making is a process of investing time and effort to make a decision that will lead to (good) results. In the following, we discuss some types of decisions that can help to design an appropriate decision making process.

According to Fitzgerald (2002, p. 9f) decisions can be roughly divided into two generic types:

- routine decisions: Decisions that must be made at regular intervals.

- non-routine: Unique, random, non-recurring decision situations.

Another common method of dividing decisions into two categories is as follows:

- Operative decisions: This type of decision usually involves day-to-day business operations. There is a lot of overlap with the routine category here. Examples of this type of decision include setting production levels, deciding whether to hire or deciding whether to close a particular plant. When it comes to decisions in our daily lives, an example would be where, what, when, and what we eat for lunch.

- Strategic decisions: This type of decision is usually about company policy and direction over a long period of time. Examples of strategic decisions include entering a new market, acquiring a competitor, or withdrawing from an industry. Renting an apartment near the university or commuting to our parents is an example of a strategic decision in our personal lives.

People often distinguish between decisions at work and private decisions. Private decisions affect fewer people on average, but usually the people involved are closer to you personally. However, both types of decisions involve the same things such as people (human resources), money (budgeting), buying and selling (marketing), how we do something (operations) or how we want to do it in the future (strategy and planning).

Some decisions are more important than others because the potential impact of a decision varies, i.e., the scope of a decision. For example, decisions can affect one person or millions, one pound/dollar or millions, one product/service or an entire market, one day or ten years, etc.

However, it is not entirely clear how to validate the scope. It depends heavily on the perspective of the decision-maker. For a small company, for example, an investment of 10,000 euros may be a big decision, while for a multinational cooperation it is a drop in the bucket. So the scope for decisions is relative, not absolute. It depends entirely on the context in which the decision is made and on the characteristics of the person(s) making it.

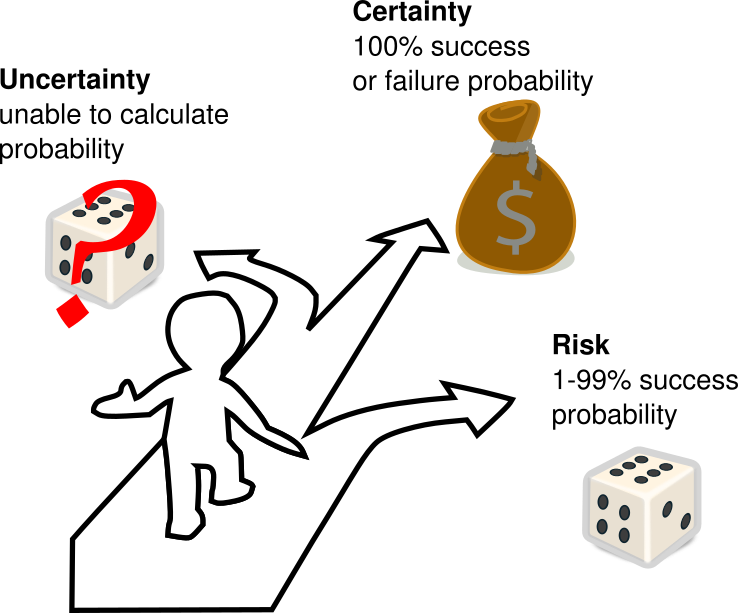

2.4 Three conditions of decision making

There are three general conditions (see 2.7) that determine the design of the optimal decision making process: certainty, risk and uncertainty.

Certainty: A condition under which taking a decision involves reasonable degree of certainty about its result, what are the opportunities and what conditions accompany this decision.

Risk: A condition under which taking a decision involves reasonable degree of certainty about its result, what are the opportunities and what conditions accompany this decision.

Uncertainty: A condition in which decision maker does not know all the choices, as well as risks associated with each of them and possible consequences.

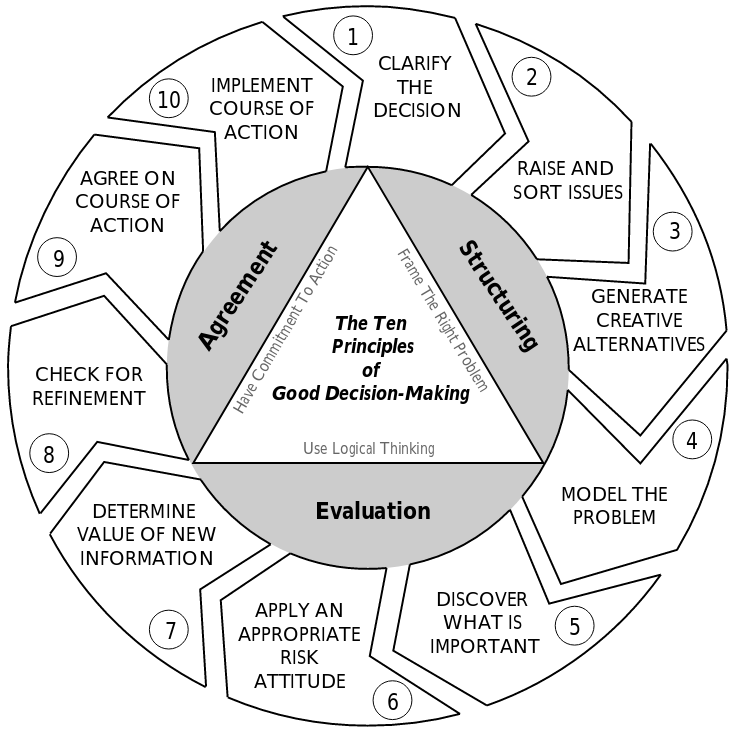

2.5 Decision making strategies

Exercise 2.4 Different schemes of a decision making process

Google for “decision making strategies” and look at the images that Google suggests you.

Read Indeed Editorial Team (2023) and discuss the twelve decision making strategies. The article can be found here.

Compare these strategies to the scheme shown in figure 2.8.

Choose a problem of your choice and try to solve the problem using the two illustrations above by making a good decision.

Discuss in class whether the diagram or the strategies in Indeed Editorial Team (2023) are helpful in making a wise decision or solving a problem.

Watch https://youtu.be/pPIhAm_WGbQ and answer the following questions: How is the nature of decisions discussed here? Does it contain a rational model of problem solving? Reflect on which ways to solve a problem and come to a decision, respectively, have been addressed.

Exercise 2.5 The businessman and the fisherman

A classic tale that exist in different version^[This one stems from thestorytellers.com. A famous version stems from Paulo Coelho^[See https://paulocoelhoblog.com and it goes like this:

One day a fisherman was lying on a beautiful beach, with his fishing pole propped up in the sand and his solitary line cast out into the sparkling blue surf. He was enjoying the warmth of the afternoon sun and the prospect of catching a fish.

About that time, a businessman came walking down the beach, trying to relieve some of the stress of his workday. He noticed the fisherman sitting on the beach and decided to find out why this fisherman was fishing instead of working harder to make a living for himself and his family. “You aren’t going to catch many fish that way”, said the businessman to the fisherman.

“You should be working rather than lying on the beach!” The fisherman looked up at the businessman, smiled and replied, “And what will my reward be?” “Well, you can get bigger nets and catch more fish!” was the businessman’s answer. “And then what will my reward be?” asked the fisherman, still smiling. The businessman replied, “You will make money and you’ll be able to buy a boat, which will then result in larger catches of fish!” “And then what will my reward be?”” asked the fisherman again.

The businessman was beginning to get a little irritated with the fisherman’s questions. “You can buy a bigger boat, and hire some people to work for you!” he said. “And then what will my reward be?” repeated the fisherman. The businessman was getting angry. “Don’t you understand? You can build up a fleet of fishing boats, sail all over the world, and let all your employees catch fish for you!”

Once again the fisherman asked, “And then what will my reward be?” The businessman was red with rage and shouted at the fisherman, “Don’t you understand that you can become so rich that you will never have to work for your living again! You can spend all the rest of your days sitting on this beach, looking at the sunset. You won’t have a care in the world!”

The fisherman, still smiling, looked up and said, “And what do you think I’m doing right now?”

Define the cost and benefits of both persons. Who do you think has a better life overall. Who is acting rationally here? In other words, who is maximizing utility here? The fishermen or the businessmen? Both? None?

2.6 The rational model

Economists view the choices that people make as rational. A rational choice is one that compares costs and benefits and achieves the greatest benefit over cost for the person making the choice. Whatever the benefits and the costs maybe, a decision maker have to consider all and make a decision. Of course, in reality it is often difficult if not impossinle to sum up benefits and costs as the nature of both may be totally different. To get rid of these problems economists use a theoretical concept that measures both in utility. That is a general and abstract measure to model worth or value. Its usage has evolved significantly over time. The term was introduced initially as a measure of pleasure or happiness within the theory of utilitarianism. It represents the satisfaction or pleasure that people receive for consuming a bundle of goods and services, for example.

According to CEOpedia (2021) rational decision making is a style of decision making based on objective data and a formal process of analysis. It excludes acting based on subjective feelings and intuitive approach. The model assumes that deducting decisions with full information and all alternatives allows for the creation of cognitive skills that allow the evaluation of all possible options and then the selection of the best one.

It essentially consists of a logical sequence of steps. Here is an example taken from Fitzgerald (2002, p. 13):

Clearly identify the problem. A problem can be defined as a perceived gap between the current reality and the desired reality.

Generate potential solutions. For routine decisions, various alternatives can be identified relatively easily using predetermined decision rules, but non-routine decisions require a creative process to find new alternatives.

Using appropriate analytical approaches, select a solution from the available alternatives, preferably the one with the largest expected value. In decision theory, this is called maximizing the expected utility of the outcomes.

Implement the solution. Managers often undermine implementation by not ensuring that those responsible for implementation understand and accept what they need to do, and that they have the motivation and resources needed for successful implementation.

Evaluate the effectiveness of the implemented decision

While these rational models may be helpful, they can also be criticized in a number of ways. In particular, it is a belief that managers actually optimize their decision behavior based on rationality because they consciously select and implement the best alternatives. This is a misconception because any rational optimization is based on a number of dubious assumptions. For example, (Fitzgerald, 2002, p. 13):

- it is hardly possible to know in advance all possible alternative solutions and to know in advance the specific outcomes that will result from each of them;

- there is actually an optimal solution, and this solution is among the alternatives identified;

- it is possible to accurately and numerically weight the various alternatives, the probabilities of their outcomes, and the relative desirability of these alternatives and outcomes;

- the decision makers always act rationally and therefore the decision making is free of emotion, bias, and politics; and

- business decisions are driven entirely by the desire to maximize profits.

The rational model can be considered normative because it prescribes a strict logical sequence of steps to be followed in any decision-making situation. The rational models are based on the assumption that human behavior is logical and therefore predictable under certain circumstances. This is not necessarily what actually happens in the real world. Consider, for example, the findings in the field of behavioral economics, which clearly show that homo economicus is a (useful) concept that is weak in several aspects.

2.7 Bounded rationality

Herbert A. Simon (1916-2001) shown in figure 2.9 received the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences in 1978 and the Turing Award10 in 1975. According to NobelPrize.org (2021), he

“combined different scientific disciplines and considered new factors in economic theories. Established economic theories held that enterprises and entrepreneurs all acted in completely rational ways, with the maximization of their own profit as their only goal. In contrast, Simon held that when making choices all people deviate from the strictly rational, and described companies as adaptable systems, with physical, personal, and social components. Through these perspectives, he was able to write about decision-making processes in modern society in an entirely new way”.

In particular, he proposed bounded rationality as an alternative basis for the mathematical and neoclassical economic modelling of decision-making, as used in economics, political science, and related disciplines.

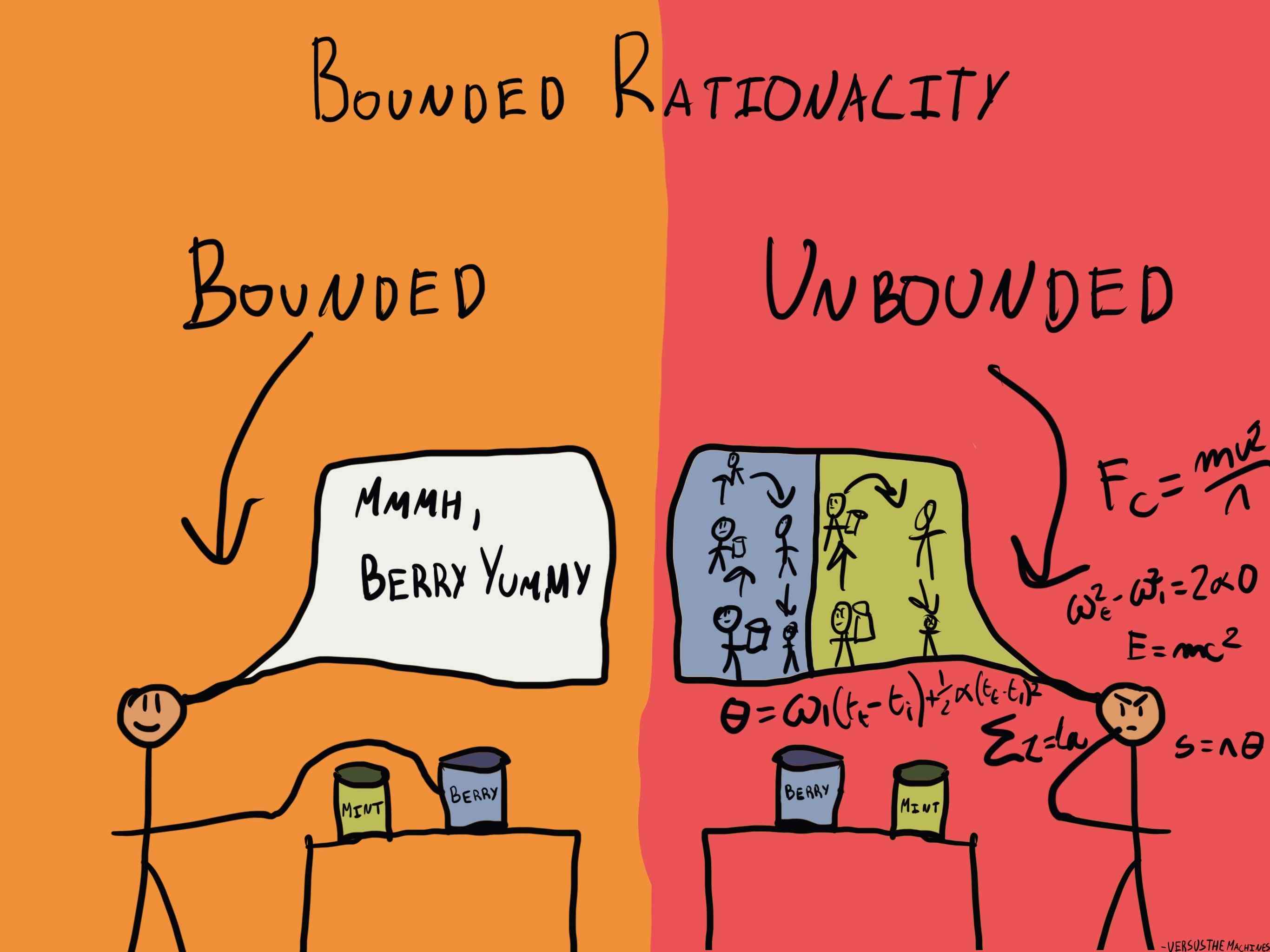

Bounded rationality proposes that decision making is constrained by managers’ ability to process information, i.e., the rationally is bounded (see figure 2.10). Managers use shortcuts and rules of thumb which are based on their prior experience with similar problems and scenarios. Given the constraints of managers in their position, they do not actually optimize their choice given the available information. It is more like finding a satisfactory solution, not necessarily the best or the optimal solution.

Exercise 2.6 Optimal vs. satisfactory solution

Using the images 2.11 to 2.14, explain the idea of bounded rationality in the context of decision making.

Please find solution to the exercise in the appendix.

Exercise 2.7 Are we irrational?

Discuss the following statement:

Since the rationality of individuals is bounded and it is obvious that individuals do not make optimal decisions, we can say that individuals act irrationally.

2.8 Homo economicus

The so-called homo economicus is often modeled by the assumption of perfect rationality. Actors are assumed to always act in a way that maximizes their utility (as consumers) and profit (as producers), and to this end they are capable of arbitrarily complex reasoning. That is, it is assumed that they are always capable of thinking through all possible outcomes and choosing the course of action that leads to the best possible outcome.

Of course, the assumption of homo economicus is heroic, and I doubt that any serious economist has ever assumed that this assumption can be found one-to-one in reality. However, it is an assumption that helps to make predictions and explain the behavior of people and societies to some extent. I mean, what would happen if microeconomics went to the other extreme assuming irrationally acting individuals. The result would be, more or less, that we would not be able to make predictions and the future would be a random walk.

Nevertheless, economists and anyone who wants to make, apply, or think about economic theories should be aware of all the pitfalls that arise in our decision making and know that our ability to act rationally is limited. In real life, we often use heuristics to solve problems and make decisions.

A heuristic is any approach to solving a problem that uses a practical method that is not guaranteed to be optimal, perfect, or rational. However, a heuristic should–at best–be sufficient to achieve an immediate, short-term goal or approximation. Overall, people use heuristics because they either cannot act completely rationally or want to act rationally but do not have the time it would take to compute the perfect solution. Moreover, the effort is probably not worth it or simply not possible given the time constraints under which the problem must be solved. A heuristic is a mental shortcut or rule of thumb to make decisions and solve problems quickly and efficiently. It helps individuals to arrive at a solution without extensive analysis or evaluation of all available information. Heuristics are usefull when time, resources, or information are limited.

While heuristics can be helpful in many situations, they can also lead to errors and biases, particularly when they are overused or misapplied. We will discuss some of these biases in section 3.5 in greater detail.

2.9 Decision trees

When we decide under certain conditions, decision trees can be a helpful tool, as explained in (Finne, 1998). If you want to know more about the use of decision trees I recommend reading Bonanno (2017, ch. 4).

2.10 Payoff table

A payoff table, also known as a decision matrix, can be a helpful tool for decision making, as shown in the table below. It presents the available alternatives denoted by \(A_i\), along with the possible future states of nature or goals denoted by \(N_j\).

The payoff or outcome depends on both the chosen alternative and the future state of nature that occurs. For instance, if alternative \(A_i\) is chosen and state of nature \(N_j\) occurs, the resulting payoff is \(O_{ij}\). Our goal is to choose the alternative \(A_i\) that yields the most favorable outcome \(O_{ij}\).

| State of nature (\(N_j\)) | \(N_1\) | \(N_2\) | \(\cdots\) | \(N_j\) | \(\cdots\) | \(N_n\) |

| Probability (p) | \(p_1\) | \(p_2\) | \(\cdots\) | \(p_j\) | \(\cdots\) | \(p_n\) |

| Alternative (\(A_i\)) | ||||||

| \(A_1\) | \(O_{11}\) | \(O_{12}\) | \(\cdots\) | \(O_{1j}\) | \(\cdots\) | \(O_{1n}\) |

| \(A_2\) | \(O_{21}\) | \(O_{22}\) | \(\cdots\) | \(O_{2j}\) | \(\cdots\) | \(O_{2n}\) |

| \(\cdots\) | \(\cdots\) | \(\cdots\) | \(\cdots\) | \(\cdots\) | \(\cdots\) | \(\cdots\) |

| \(A_i\) | \(O_{i1}\) | \(O_{i2}\) | \(\cdots\) | \(O_{ij}\) | \(\cdots\) | \(O_{in}\) |

| \(\cdots\) | \(\cdots\) | \(\cdots\) | \(\cdots\) | \(\cdots\) | \(\cdots\) | \(\cdots\) |

| \(A_m\) | \(O_{m1}\) | \(O_{m2}\) | \(\cdots\) | \(O_{mj}\) | \(\cdots\) | \(O_{mn}\) |

If we assume that all objectives are independent from each other and that we are certain about the state of nature, the decision is rather trivial: just go for the alternative with the best outcome for each state of nature. However, most real-world scenarios are not that simple because most states of nature are more complex and needs further to be considered.

2.11 Review

- Decision analysis is about using information in order to come to a decision.

- A structured and rational process can help improve the chances of receiving good decision outcomes.

- As decision problems are often (too) complex to fully capture or solve rationally. Thus, a good decision analysis should try to use the available information and the existing understanding of the problem as transparent, consistent, and logical as possible.

- A complex decision problem should be simplified and hence decomposed into its basic and most important components.

- There are hundred of different schemes or strategies how to make decisions in certain circumstances. Many heuristics exist how to think, behave, and calculate to come to a wise decision.

- Mostly decisions are based on subjective expectations. These expectations are difficult to validate.

- Articulating exact expectation and preferences is a difficult task and the information that stems from these articulation is full of biases. Decision analytic tools need to take that into consideration.

Exercise 2.8 Lisa is pregnant

The following question stems from a study carried out by Kahneman & Tversky (1972): Lisa is thirty-three and is pregnant for the first time. She is worried about birth defects such as Down syndrome. Her doctor tells her that she need not worry too much because there is only a 1 in 1,000 chance that a woman of her age will have a baby with Down syndrome. Nevertheless, Lisa remains anxious about this possibility and decides to obtain a test, known as the Triple Screen, that can detect Down syndrome. The test is moderately accurate: When a baby has Down syndrome, the test delivers a positive result 86 percent of the time. There is, however, a small ‘false positive’ rate: 5 percent of babies produce a positive result despite not having Down syndrome. Lisa takes the Triple Screen and obtains a positive result for Down syndrome.

Given this test result, what are the chances that her baby has Down syndrome?

- 0-20 percent chance

- 21-40 percent chance

- 41-60 percent chance

- 61-80 percent chance

- 81-100 percent chance

Think about the question and put your answer here:

https://pingo.coactum.de/ Code: 666528

Please find solution to the exercise in the appendix.

Picture is taken from https://pixabay.com/de/illustrations/entscheidung-auswahl-pfad-stra%C3%9Fe-1697537/↩︎

Picture is taken from https://pixabay.com/de/illustrations/entscheidung-auswahl-pfad-stra%C3%9Fe-1697537/↩︎

Picture is taken from Nobel Foundation archive ↩︎

The Turing Award is an annual prize given by the Association for Computing Machinery (ACM) for contributions of lasting and major technical importance to the computer field. It is generally recognized as the highest distinction in computer science and is known as or often referred to as `Nobel Prize of Computing’.↩︎

Picture is taken from https://thedecisionlab.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/Bounded-Rationality.jpg ↩︎