9 Out-of-lab experiments

9.1 Difference in difference

Source: https://davidcard.berkeley.edu.

David Card is one of the most influential labor economist of the 20th century and Nobel laureate of 2021. He is well-known for his research on the effects of the minimum wage on employment, which challenged the traditional view that increasing the minimum wage leads to a decrease in employment. In his article Minimum Wages and Employment: A Case Study of the Fast-Food Industry in New Jersey and Pennsylvania (Card & Krueger, 1994) he and Alan Krueger (1960-2019) used a natural experiment to examine the effect of an increase in the minimum wage on employment. In particular, they identified a treatment group (restaurants in New Jersey) and a control group (restaurants in eastern Pennsylvania) to measure the effect of increasing the minimum wage that was increased in New Jersey but not in Pennsylvania. This increase did not lead to a decrease in employment, which contradicted the widely held view that increasing the minimum wage would lead to job loss. The empirical method that they used is called difference in difference and we discuss it in the following section.

The difference in difference (DiD) method allows to estimate the causal effect of a treatment or intervention. In particular, it is popular to study the impact of policy changes and other interventions on a specific outcome of interest.

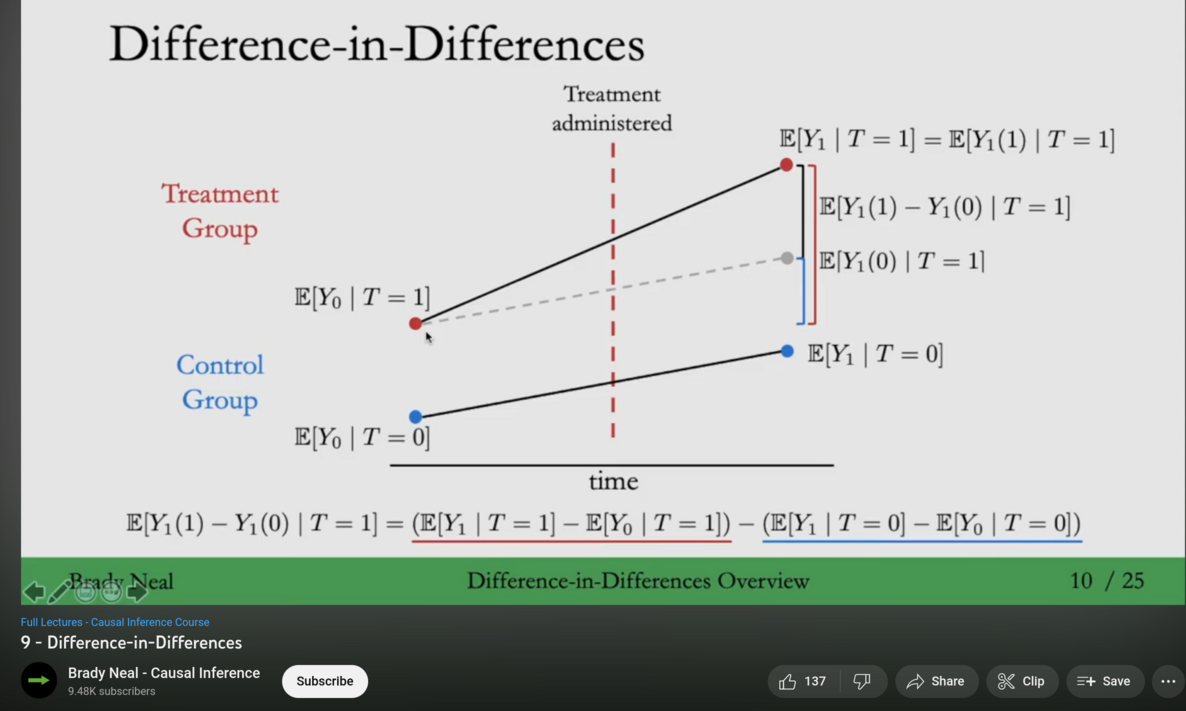

The basic idea behind the DiD method is to compare the change in an outcome variable between a treatment group and a control group over time. The treatment group is the group that is exposed to the intervention or treatment, while the control group is a group that is not exposed to the intervention. The difference in the change in the outcome variable between the two groups is then used to estimate the causal effect of the intervention.

To use the DiD method, researchers typically collect data on the outcome variable of interest for both the treatment and control groups before and after the intervention. This data is then used to calculate the difference in the change in the outcome variable between the two groups.

For example, if a study aims to examine the effect of a new policy on the employment rate, it should collect data on the employment rate for a group of individuals living in a region where the policy was implemented, and for a group living in a similar region where the policy was not implemented. The study can then compare the change in the employment rate for the two groups, before and after the implementation of the policy. The difference in the change in the employment rate between the two groups can be used to estimate of the causal effect of the policy on employment.

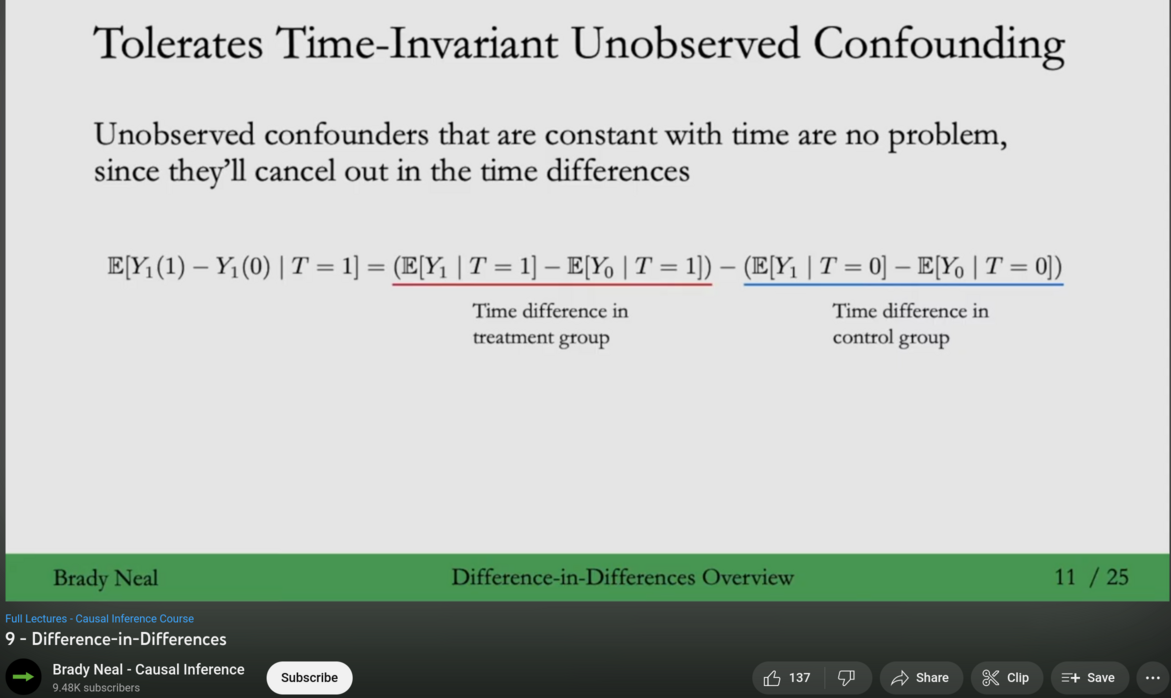

It is important to note that DiD assumes that there are no other factors that could be affecting the outcome variable of interest and that the treatment and control groups are similar in all ways except for the intervention. To control for these assumptions researchers can use statistical techniques such as matching to ensure that treatment and control groups are similar before the intervention.

DiD is useful when we only have observational data and in situations where it is not possible or ethical to randomly assign individuals to a treatment or control group, for example, in the case of policy changes.

Differences-in-Differences and Rubin causal model

Figure 9.2 and Figure 9.3 stem from a video of Brady Neal’s lecture on Difference-in-Differences. Please watch this video.

In Section 3.4, I introduced how experiments can be used to identify causes of effects and measure the impact of those causes using randomized controlled trials (RCTs). However, my previous description of experiments conducted outside of a laboratory setting—where researchers cannot as easily and precisely manipulate the independent variable—was brief. In this section, I will provide more detailed explanations.

9.2 Natural experiments

In social science, a natural experiment is a research design that exploits naturally occurring circumstances or events to study the effects of an intervention or treatment. In these experiments, the treatment is not manipulated by the researcher, but is instead determined by exogenous, or external, factors. Exogenous variations refer to changes in the independent variable that are not caused by the researcher’s actions but instead occur naturally or through some external factor. These variations are often unpredictable and occur without the intervention of the researcher, making them an ideal source of variation to study the causal effects of a treatment or intervention. One example of a natural experiment is the partition of Germany after World War II, which created two economies that were initially similar but experienced vastly different economic and institutional environments. Another example is the introduction of a new policy or technology in one state or country but not in another, allowing for a comparison of outcomes before and after the treatment. A natural experiment might involve comparing the outcomes of two groups of people who were exposed to different levels of air pollution due to a policy change or a natural disaster. In this case, the variation in air pollution levels is exogenous, since it is not controlled by the researcher but rather determined by external factors.

By leveraging these exogenous variations, researchers can better estimate the causal effects of an intervention or treatment, and provide evidence for policy-makers to make more informed decisions. In the following, we will get known to some studies that are based on natural experiments.

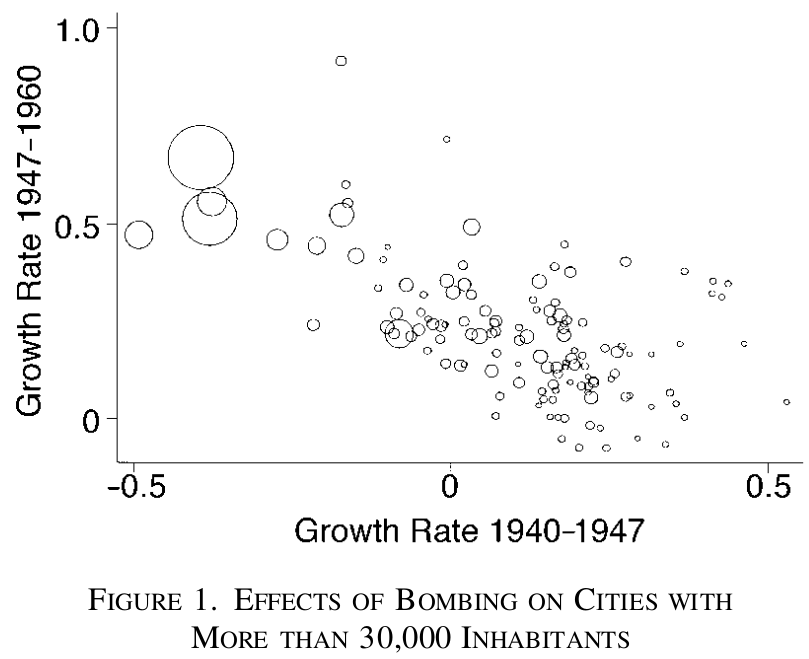

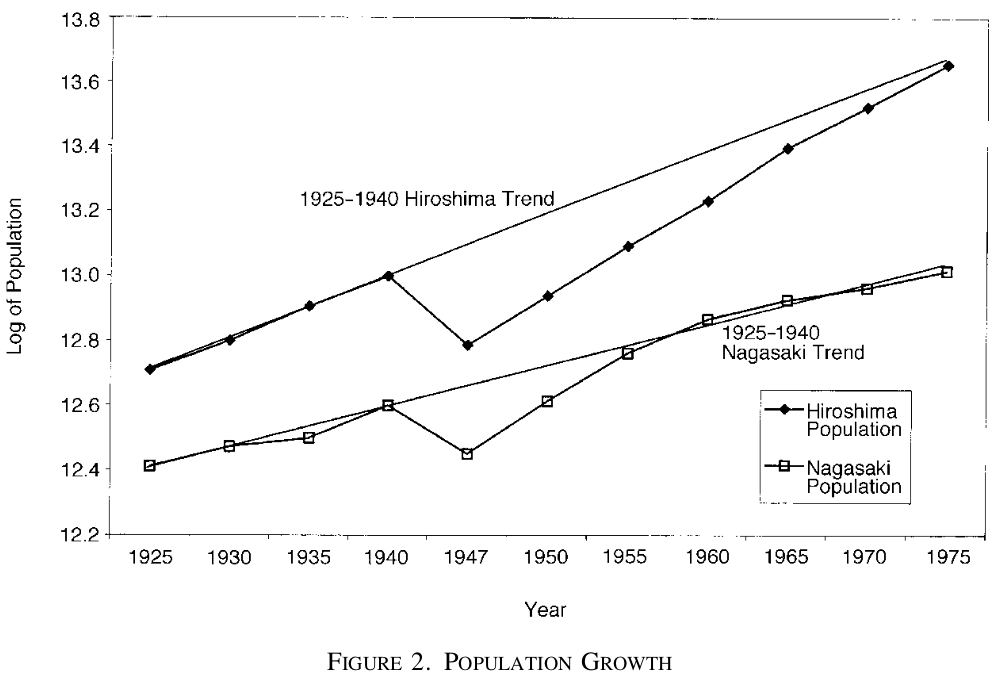

9.3 Case study: Bombing of Japan

In their article “Bones, Bombs, and Break Points: The Geography of Economic Activity,” Davis & Weinstein (2002) explore another natural experiment that has shaped the economic geography of the world: the natural endowment of different regions with physical and institutional factors that affect their productivity and attractiveness to economic activity. Using a spatial econometric model, they test the relative importance of three such factors: climate, natural resources, and political borders. They find that political borders, such as the ones that emerged from colonialism or ethnic conflict, have the strongest effect on economic activity, even after controlling for other factors. This has important implications for policy, as it suggests that changing the institutional environment of a region can have a significant impact on its economic performance.

Overall, Davis and Weinstein’s article demonstrates the power of natural experiments to shed light on important economic questions and inform policy debates. By examining the historical and geographical factors that have shaped economic activity around the world, they offer valuable insights into the mechanisms that drive economic growth and inequality.

Before you read this article, let me explain that the theory which this article elaborates and tests goes back to the 2008 nobel-prize winner Paul Krugman (*1953) who founded the so-called New Economic Geography (NEG). Here is an excerpt of how the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences summarizes Krugman’s contribution to the field (The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, 2008, p. 3):

Economic geography deals not only with what goods are produced where, but also with the distribution of capital and labor over countries and regions. The approach Krugman used in his foreign trade theory – the assumption of economies of scale in production and a preference for diversity in consumption – was also found to be appropriate for analyzing geographical issues. This allowed Krugman to integrate two disparate fields in a cohesive model.

The embryo of the theory which would come to be called the ``new economic geography’’ had already appeared in Krugman’s 1979 article. In the final pages, he asks what would happen if foreign trade became impossible, for instance due to excessively high transport costs or other obstacles. His line of reasoning is as follows. If two countries are exactly alike, then welfare will be the same in both countries. But if the countries are alike in all respects except that one of them has a slightly larger population than the other, then the real wages of labor will be somewhat higher in the country with more inhabitants. The reason is that firms in the more highly populated country can make better use of economies of scale, which implies lower prices to consumers and/or greater diversity in the supply of goods. This, in turn, enhances the welfare of consumers. As a result, labor, i.e., consumers, will tend to move to the country with more inhabitants, thereby increasing its population. Real wages and the supply of goods will then continue to increase even more in that country, thereby giving rise to further migration, and so on.

Twelve years would pass, however, before Krugman reconsidered these ideas. In an article published in 1991, he developed these concepts into a comprehensive theory of location of labor and firms. Here, he assumes that although trade is possible, it is obstructed due to transport costs. Otherwise, labor is free to move to the country or region which can offer the highest welfare, in terms of real wages and diversity of goods. Firms’ location decisions imply a trade-off between utilizing economies of scale and saving on transport costs.

Concentration or Decentralization?

The above considerations evolved into the so-called core-periphery model, which shows that the relation between economies of scale and transport costs can result in either concentration or decentralization of communities. Under certain conditions, the forces which contribute to concentration will dominate. Regional imbalances arise and most of the population will be concentrated in a high-technology core, whereas a small minority will inhabit the periphery and live off agriculture. Such a mechanism could underlie the explosive urbanization witnessed today throughout the world, with rapidly growing megacities surrounded by increasingly depopulated rural areas. This is not necessarily the only possibility, however. Under different conditions, the forces which give rise to decentralization will dominate. This promotes somewhat more balanced development. Krugman’s model can be used to account for the mechanisms at work in both directions. For example, his model indicates that declining transport costs easily generate concentration and urbanization – which seems particularly noteworthy since transport costs have exhibited a declining trend throughout the twentieth century.

Numerous research papers inspired by Krugman’s New Economic Geography (NEG) focus on the origins and implications of the so-called first and second nature effects. These effects are used to explain the uneven distribution of economic activity both across countries and within regions of a country. Two primary explanations have been investigated: (1) Fundamentals, which refer to differences in the fundamental productivity of locations, and (2) Agglomeration forces, which are related to the proximity of economic agents that boost productivity and make a location more attractive.

These two mechanisms are obviously not exclusive and can both operate simultaneously. The key empirical question is to what extent observed patterns of economic activity are explained by these two mechanisms. Understanding whether fundamentals or agglomeration forces are responsible for the pattern of economic activity has significant implications for the persistence of spatial equilibria and policy making.

For example, suppose only agglomeration forces are at play. In that case, the location of economic activity is relatively arbitrary, and a particular location is attractive mainly because other workers are choosing to locate there. This phenomenon is similar to selecting a nightclub: club A is crowded and everybody wants to be there only because it was the club had attracted the first person that night.

In contrast, if only fundamentals are in operation, the distribution of activity is determined by the distribution of these underlying factors. When agglomeration forces dominate fundamentals, the spatial distribution of activity becomes a matter of political interest. For example, regional policies can aim to move the distribution of economic activity between different equilibria. Using a temporary subsidy, regions can try to attract a ‘critical mass’ of economic activity. Once established, this critical mass will make the location more attractive, even when the subsidy has ended.

This approach is similar to nightclub policies, such as offering free entry or other discounts to the first people who are searching for a club. These incentives are an attempt to attract a critical mass of party-goers, making the nightclub more attractive and increasing the likelihood that other party-goers will choose the same club later.

9.4 Field experiments: Would you work more if wages are high?

Unlike laboratory experiments, which are conducted in a controlled environment, field experiments are conducted in real-world settings, such as schools, workplaces, and communities. They allow for testing causality by controlling the independent variable while observing the dependent variable in a naturalistic setting. They are a valuable tool for testing the effectiveness of policies and interventions in real-world situations. The level of external validity is usually much higher than alternative methods, meaning that the results can be generalized to other similar contexts beyond the specific setting where the experiment was conducted. In addition, field experiments can help identify unintended consequences of policies or interventions that might not be observable in laboratory experiments or observational studies.

Another advantage of field experiments is that they can be used to test theories in contexts where observational studies may be limited. For example, a theory may predict that a certain policy or intervention will have a specific effect, but it may be difficult to test this theory through observational studies due to confounding variables or selection bias.

However, field experiments can be costly and time-consuming to conduct. Please give Harrison & List (2004) article a quick read, as it explains the nature and advantages of field experiments well.