7 Good research

Data is everywhere in today’s world, and access to data and facts on almost any topic is more affordable than ever. Howver, the abundance of information often leads to confusion and risks drawing the wrong conclusions. Even as a professor of data science, I sometimes feel overwhelmed by the sheer amount of information available.

While researchers, businesses, and individuals use facts to gain insights that are relevant to their interests, not everyone is trained to interpret data effectively, making it difficult to turn raw data into real insights.1 Many people (intentionally or unknowingly) misuse and misinterpret information and also scientific content. Many research papers exist that misapply empirical methods and therefore produce biased results or hide or disguise the potential weaknesses of the results. Numerous predatory journals are full of papers that have not undergone the rigorous peer review process typical of reputable publishers that strive to maintain qualitative standards.

1 I admit that it can be difficult to gain insights that really stand the test of time. Most empirically oriented scientists I know present their results with modesty, knowing well how heroic it is to claim to have “found evidence” in a social science study. Unfortunately and paradoxically, this modesty explains to some extend why some people are more fascinated by wrong but simple explanations presented by people with dishonest intentions.

In this chapter, I will discuss how to evaluate quantitative information from public sources Section 7.1, assess the quality of academic publications Section 7.3, and identify literature of uncertain quality Section 7.4.

7.1 Information and insights

The information and the data you come across in private and professional contexts often comes from sources with specific interests that have reasons to manipulate your perception. These manipulators usually present their arguments and insights in a polemical manner and disregard counter-arguments that could weaken their position.

Without the ability to critically evaluate information and the insights derived from it, it’s easy to be manipulated by persuasive narratives. Manipulators work diligently to come up with convincing stories that feel intuitively right. For example, the tobacco industry has long successfully promoted the idea that smoking is healthy.

I see two effective strategies for recognizing manipulators, becoming a more discerning consumer of information, and improving your ability to refute fallacious arguments that yield to false insights. Firstly, identify manipulators and, secondly, be educated enough to evaluate the arguments or to consult an objective expert that can evaluate the information for you.

To recognize manipulative arguments, you should familiarize yourself with the tactics manipulators use. Below, I explain some methods manipulators use to create narratives that resonate emotionally while using misleading information to lead readers to desired conclusions:

- Emotional appeals: Manipulators often evoke fear or pity to trigger emotional responses that can undermine critical thinking. Such emotional appeals should raise suspicions about the intentions of the information provider because it is difficult to be objective when you are charged with emotion.

- Selective data presentation: Manipulators frequently cherry-pick statistics that support their arguments while ignoring contrary evidence, skewing the overall picture. A one-sided presentation sometimes demonstrates the author’s unwillingness to challenge their views.

- Manipulative language: This includes language designed to distort facts or exaggerate claims, creating an illusion of certainty or urgency that can easily mislead.

- Pseudo-expertise: Manipulators may present themselves as authorities or experts, despite lacking the appropriate credentials to back up their claims.

- Citing research: By referencing and citing research findings, manipulators capitalize on the fact that most people would have a hard time effectively disputing these claims.

Recognizing these tactics can create skepticism in the right place and motivate you to critically evaluate the claims that are being made.

To challenge manipulative arguments, you need to study the subject on your own. This often requires a solid understanding of both quantitative and qualitative research methods. I hope this course and the lecture notes can assist you in building that understanding. However, if you feel that you lack these skills, I highly recommend consulting an objective expert. The alternative is to risk becoming a potential victim of manipulation.

7.2 Case study: Dogs and Votes

In business, politics, and personal life, individuals often need to gather information in fields outside their expertise to make informed decisions. The information encountered in these situations is frequently complex and challenging to understand. Therefore, it is essential to find a reliable source that offers valid and trustworthy insights. This can be a significant challenge. Evaluating the reputation of the organization and the author of the information is one strategy to avoid low-quality data, but even this can be difficult to ascertain in certain fields.

In this section, I discuss the studies by Lippert & Sapy (2003) and Curtis et al. (2021). The first study examines the quality of dog food and the life expectancy of dogs, while the latter focuses on human life expectancy and voting behavior, specifically the tendency to vote for Republicans. Despite lacking expertise in veterinary or political science, our background in quantitative methods and scientific analysis allows us to identify Lippert & Sapy (2003) as a prime example of poor research design, where empirical methods are misapplied and results are misinterpreted. This study invites readers to draw misleading conclusions and misuse the findings presented. In contrast, the study by Curtis et al. (2021) demonstrates a much stronger research approach.

Both cases should illustrate how the knowledge you gain in this course can enhance your ability to inform yourself more effectively by enabling you to evaluate the quality of the information you encounter.

7.2.1 Lippert & Sapy (2003): Life expectancy of dogs

If you love your dog, you naturally want him to live a long and happy life. However, uncovering the secrets to dog longevity can be challenging. Unlike humans, dogs don’t choose their food because they usually only eat what their owner feeds them. Therefore, owners have a responsibility to educate themselves on a proper diet for their dogs.

A quick Google search can yield a wealth of information about dog longevity. For example, here is an excerpt from luckydogcuisine.com, a company that provides fresh cooked food for dogs:

“Diet does help dogs live longer!

Here at Lucky Dog Cuisine, we believe in feeding fresh foods to our dogs. We have been doing this for over 50 years and with good reason!

In a study out of Belgium, “Relation between the Domestic Dogs: Well-Being and Life Expectancy, a statistical essay”, used data gathered from more than 500 domestic dogs over a five year time frame (1998 to 2002).

Drs. Lippert and Sapy, the authors showed statistically that dogs fed a homemade diet, consisting of high quality foods (not fatty table scraps) versus dogs fed an industrial commercial pet food diet had a life expectancy of 32 months longer – that’s almost 3 years!

It is the quality of the basic ingredients and the way they are processed that makes the difference. High heat cooking, extrusion and flaking as well as chemical treatment using preservatives and additives were found to be factors in destroying ingredient integrity.

Our fresh foods are cooked the old fashioned way using steam and then frozen. No chemicals or preservatives ever!

We’re excited to be a part of helping dogs live longer and healthier lives.”

After reading this blog post, you may feel compelled to buy high-quality food and prepare fresh meals for your dog. However, before you invest your money, you should review the information presented. After all, it comes from a company that wants to make a profit by selling fresh dog food. Therefore, you decide to do further research and read the article the blog references. As the provided link to the paper does not work, you search for the authors in literature databases such as PubMed and Google Scholar but without any results, likely because the paper has not been published in any journal or scholarly literature. After some effort with the unrestricted Google search engine, I found the paper by Lippert & Sapy (2003). It appears to be an essay that was once submitted for a prize from the Prince Laurent Foundation.

The authors write in their essay (Lippert & Sapy, 2003, p. 5):

“Our objective is to study the influence of these various parameters on the life expectancy of the dog. The statistical use of more than 500 “DOGS’ LIFE SHEETS or DOGS’ FAMILY BOOK”, collected during five years, from 1998 until 2002, will be our basic working material and will serve to extract a causality connection between quality of life, animals’ well-being and life expectancy.

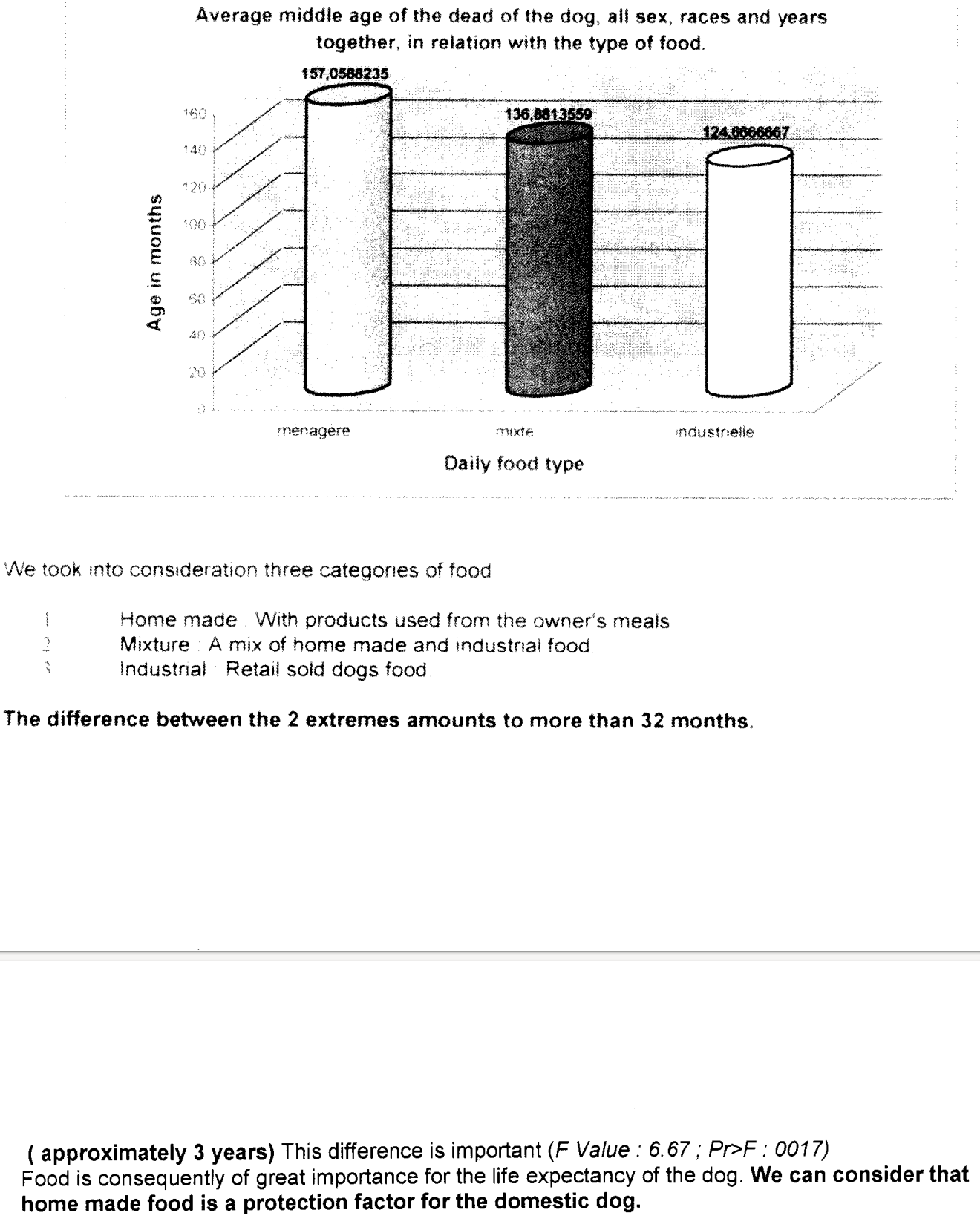

We took into consideration three categories of food 1. Home made: With products used from the owner’s meals 2. Mixture: A mix of home made and industrial food 3. Industrial: Retail sold dogs food

The difference between the 2 extremes amounts to more than 32 months. ( approximately 3 years)** This difference is important (F Value : 6.67 ; Pr>F : 0017). Food is consequently of great importance for the life expectancy of the dog. We can consider that home made food is a protection factor for the domestic dog.

In Figure 7.1, I show a screenshot of the relevant pages, providing insight into the impact of food on life expectancy Lippert & Sapy (2003) claim to have found.

Source: Lippert & Sapy (2003, pp. 12–13).

There are several flaws and issues in this paper. Foremost, the interpretation of the presented results is false. Before going into details, let us clarify the meaning of the three numbers shown in the figure: They represent the average lifespan, in months, of dogs across three categories. Dogs fed with “products used from the owner’s meal” lived an average of about 157 months, those fed a “mix of homemade and industrial food” reached about 136 months, and dogs that consumed “retail-sold dog food” lived for about 124 months.

Here is an incomplete list of the weaknesses identified in the study:

Pseude-expertise:

- There are several issues, such as punctuation and spacing errors, as well as the figure mixing English and French terms while employing a three-dimensional format that is difficult to read. Additionally, the inconsistent use of bold and italics can be confusing. While these issues may seem minor, they indicate a lack of attention to detail on the part of the authors and raise doubts about the professionalism of the researchers. Although these factors may not directly affect the scientific quality of the investigation, they often correlate strongly with it and are relatively easy for readers to identify.

- The authors claim to test the differences “between the two extremes.” While it seems clear they mean the averages of homemade-fed dogs versus industrially-fed dogs, they are looking at averages, not extremes. The language used is unclear.

- In the acknowledgments, they thank several individuals for their “priceless assistance”, “erudition in statistics”, “translation into English”, and for their willingness “to read and correct the translation”. While it is commendable that they acknowledge this help, the overall impression of the article raises doubts about their academic proficiency and independence. For example, they do not relate their contribution to the current state of research as they do not have a reference list. Moreover, the dataset, with 522 observations and a dozen variables, does not appear particularly sophisticated, and the statistical tasks do not exceed the level of a Statistics 101 course. This raises the question of why two doctors of science require assistance with statistics.

Manipulative language:

- The term ‘approximately’ implies closeness; however, 36 months (three years) is actually 12.5% greater than 32 months, indicating it is not a close estimate as the authors want us to believe. A closer approximation would be two and a half years.

- The only statistical test referenced appears to be a mean difference test. The authors misinterpret this statistical significant difference by stating that “the difference is important.” Statistical significance does neither imply importance nor causality (see Section 3.3).

- Comparing the averages of two groups of dogs that are statistically different, they conclude that

- “Food is consequently of great importance for the life expectancy of the dog”,

- “home made food is a protection factor for the domestic dog”, and

- “animals who receives varying home made food, will have the benefit of a longer life expectancy.”

Selective data representation:

- The authors neither provide details on their statistical analyses nor on their data. We don’t know the sample sizes for each group, nor is the standard deviation provided for the statistics shown. The reproducibility of the paper is not given, and the transparency of their data work is low. I will discuss these issues in greater detail in Section 7.3.

Methodological issues:

As we learned in Section 3.3, differences in the averages of the treated (homemade food) and untreated (industrial food) groups can indicate a causal effect, assuming the conditions of ignorability and unconfoundedness hold. However, the authors provide no evidence that these assumptions are satisfied. In fact, the remainder of the article presents strong arguments suggesting that these assumptions do not hold.

The dogs were not randomly assigned to the groups. The authors do not rule out the possibility that group assignments were based on characteristics such as weight, breed, and gender, which they also find associated with life expectancy. For example, larger dogs may be less likely to be fed homemade food due to the greater cost and effort required. The authors noted that breeds like Pyrenean Mountain and Big Danish dogs lived significantly shorter lives on average than smaller breeds like Poodles and Yorkshire. Thus, differences in size and other factors alike could be responsible for the observed group differences. The authors do not discuss the composition of the two groups and do not appear to have made efforts to ensure comparability. For example, they could have compared homemade-fed Poodles with Poodles fed industrially.

Even if the groups were similar, the observed averages may be influenced by confounding factors. For example, it is plausible that dogs receiving more expensive homemade food are treated differently across various aspects, including medical care-factors that may contribute to life expectancy. If this is the case, the dogs might not live longer because of the food but rather due to other factors correlated with the type of food they receive. This illustrates a classic case of bias due to omitted variables.

Overall, the information provided in the study should not be used to make causality claims about the life expectancy of dogs on average. The two authors merely compared two different groups of dogs without controlling for confounding factors and without addressing potential sources of bias.

7.2.2 Curtis et al. (2021): Life expectancy of humans

To clarify this issue further and end with a better example, consider the example from Curtis et al. (2021), which found that life expectancy within regions is positively associated with the Democratic share of votes in 2016 and 2020. However, the authors do not assert a causal relationship using sensationalist language like “voting for Republicans kills”. Instead, they critically discuss the correlations while being aware of potential sources of bias that may influence the correlation, and they do not appear to have any obvious interests in misleading the reader or over-selling their results. For example, they emphasize that the

“associations were moderated by demographic, social and economic factors that should drive health policy priorities over the coming years”

and that their

“study is limited by its ecological nature and the inability to associate individual voting behaviors with health outcomes. Additionally, the study is limited by available data sources and would benefit from more detailed social and economic data.”

Moreover, the article was published in SSM - Population Health, a well-received peer-reviewed journal from Elsevier, which is managed by professionals from prestigious universities, including Harvard and RMIT University.

7.3 Reproduceability and transparency

While we have already addressed essential characteristics of good research such as validity and reliability see 2.5, we have not explicitly discussed how to recognize high-quality research in academic publications.

The quality of research depends largely on the honesty of the researcher and the transparency of the methods used. Although there is no absolute measure of honesty, certain indicators can provide some insight. For example, the reputation of the researcher, the institution with which he or she is associated and the credibility of the publisher, editor or journal can serve as helpful pointers. If a researcher is highly regarded in the academic world or in public life, he has much to lose by compromising his integrity. Unfortunately, this logical argument does not exclude the possibility that even respected individuals may occasionally engage in dishonest practices. History has shown that this can happen. Nevertheless, the more someone has to lose by being dishonest, the less likely they are to cheat, plagiarize, or falsify data and results, respectively.

A clear empirical methodology forms the foundations of any empirical research work. However, to ensure the wide dissemination of a study, two aspects are crucial: accessibility and dissemination. Nowadays, public accessibility of a paper is relatively easy to achieve because anyone can upload their work online to ensure its availability. Dissemination, however, is more complex. While there are various strategies to increase the popularity of a paper, the traditional and arguably most effective method is to publish the paper in a high-impact journal or a popular journal with a large readership. The successful placement of a paper in such journals is almost an art form. The paper must fulfill several criteria as well as possible: a sound methodology, a clear contribution, thematic relevance and a compelling text that appeals to the journal’s readership are just some of the key benchmarks.

How can you learn to publish a paper successfully? I think that it is crucial to study papers that have gained recognition and make an effort to recognize the reasons for their success. Doing so sharpens your writing skills, improves your perceptiveness as a researcher, and helps you to select important research topics and to design research projects more efficiently.

Prestigious journals like the American Economic Review and the Journal of Economic Literature, published by the American Economic Association (AEA), have refined and enhanced their guidelines over time. These rules are often regarded as a benchmark in academic publishing, not necessarily because they set the highest possible standards, but because they strike a balance that takes into account the practical realities faced by researchers, reviewers, and editors. Moreover, readers often prefer a swift review process, too, because they want papers that connect with current events. In that respect, it’s important to acknowledge the inherent trade-off journals must navigate: stringent standards can slow the pace of research and publication. This is particularly critical in fields like economics and business, where timely insights can significantly impact politics and society, addressing urgent needs.

This section looks at the AEA’s publishing standards. The path to publication with the AEA, particularly for empirical research, has changed considerably and is now governed by strict criteria. It is imperative that authors familiarize themselves with the key considerations and guidelines for submitting empirical research to an AEA journal. Although standards may vary across disciplines, the AEA’s exacting standards have influenced a wide range of social science journals. Engagement with these standards is invaluable as it provides guidance in designing and planning research that meets these rigorous requirements.

While each AEA journal has its specific focus and requirements, all aim for integrity, clarity, and replicability of empirical research. Authors should start by carefully reviewing the author guidelines for their targeted journal, paying close attention to any specific mandates regarding empirical work. For Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs), for example, a registration is required for all applicable submissions prior to submitting, see RCT Registry Policy.

Visit www.socialscienceregistry.org and inform yourself about some registered RCTs.

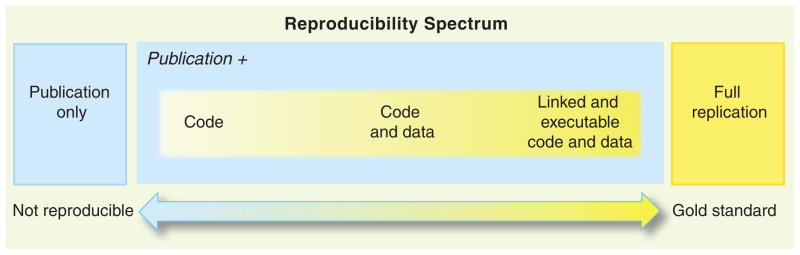

The AEA has placed a significant emphasis on the transparency and replicability of empirical research with the objective of ensuring that the empirical results can be fully replicated (see Figure 7.2). But why is replicability so crucial? Well, trust is good, control is better. Or, as Peng (2011, p. 1226) put it:

“Replication is the ultimate standard by which scientific claims are judged. With replication, independent investigators address a scientific hypothesis and build up evidence for or against it. The scientific community’s “culture of replication” has served to quickly weed out spurious claims and enforce on the community a disciplined approach to scientific discovery.” the Authors are required to ensure that their data and methodologies are openly available and clearly described, allowing other researchers to replicate their results. This commitment to transparency extends to the publication of data sets, code, and detailed methodological appendices, which must accompany the submitted manuscript.

Table 7.1 is taken from Nosek et al. (2015) and it breaks down how scientific journals ask researchers to follow more strict rules, from Level 0 to Level 3, across eight different important categories. All these standards follow the objective to come closer to the gold standard shown in Figure 7.2.

| Level 0 | Level 1 | Level 2 | Level 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Citation Standards | |||

| Journal encourages citation of data, code, and materials—or says nothing. | Journal describes citation of data in guidelines to authors with clear rules and examples. | Article provides appropriate citation for data and materials used, consistent with journal’s author guidelines. | Article is not published until appropriate citation for data and materials is provided that follows journal’s author guidelines. |

| Data Transparency | |||

| Journal encourages data sharing—or says nothing. | Article states whether data are available and, if so, where to access them. | Data must be posted to a trusted repository. Exceptions must be identified at article submission. | Data must be posted to a trusted repository, and reported analyses will be reproduced independently before publication. |

| Method Transparency (Code) | |||

| Journal encourages code sharing—or says nothing. | Article states whether code is available and, if so, where to access them. | Code must be posted to a trusted repository. Exceptions must be identified at article submission. | Code must be posted to a trusted repository, and reported analyses will be reproduced independently before publication. |

| Material Transparency | |||

| Journal encourages materials sharing—or says nothing. | Article states whether materials are available and, if so, where to access them. | Materials must be posted to a trusted repository. Exceptions must be identified at article submission. | Materials must be posted to a trusted repository, and reported analyses will be reproduced independently before publication. |

| Design Transparency | |||

| Journal encourages design and analysis transparency or says nothing. | Journal articulates design transparency standards. | Journal requires adherence to design transparency standards for review and publication. | Journal requires and enforces adherence to design transparency standards for review and publication. |

| Preregistration: Study | |||

| Journal says nothing. | Journal encourages preregistration of studies and provides link in article to preregistration if it exists. | Journal encourages preregistration of studies and provides link in article and certification of meeting preregistration badge requirements. | Journal requires preregistration of studies and provides link and badge in article to meeting requirements. |

| Preregistration: Analysis Plan | |||

| Journal says nothing. | Journal encourages preanalysis plans and provides link in article to registered analysis plan if it exists. | Journal encourages preanalysis plans and provides link in article and certification of meeting registered analysis plan badge requirements. | Journal requires preregistration of studies with analysis plans and provides link and badge in article to meeting requirements. |

| Replication | |||

| Journal discourages submission of replication studies—or says nothing. | Journal encourages submission of replication studies. | Journal encourages submission of replication studies and conducts blind review of results. | Journal uses Registered Reports as a submission option for replication studies with peer review before observing the study outcomes. |

Besides adhering to the guidelines summarized in Table 7.1, authors should also:

- Justify their choice of methodology: The paper should clearly explain why the chosen method is appropriate for the research question at hand.

- Detail the analytical process: From data collection to analysis, each step should be meticulously detailed, allowing for the study’s replication.

- Address potential limitations: No empirical study is without its limitations. Authors should openly discuss these, including any biases, measurement errors, or external factors that may impact the results.

While statistical significance is a key metric for empirical analysis, the AEA also places a strong emphasis on the economic relevance and implications of the findings. Authors should not only present statistically significant results but also explain their economic significance.

The AEA employs a rigorous double-blind peer review process that ensures that submissions are peer-reviewed without revealing the identity of the authors or reviewers. The editor of the respective journal is responsible to manage the process which involves identifying qualified reviewers and forwarding the paper to them for evaluation. This procedure serves to ensure the integrity and impartiality of the evaluation. Authors should be prepared to receive feedback and constructive criticism, which often requires a revision of the manuscript. A willingness to engage constructively with this feedback is crucial to refining the work and improving its chances of publication. Of course, this process has its disadvantages: It is slow and imposes a significant workload on both reviewers and editors. Considering the vast number of publications each year—a number that has significantly increased over the last few decades (see Paldam, 2021) and the fact that the guidelines of many journals have become stricter during the same period, it raises a question. Have researchers become miraculously more productive, or are they simply working more?

7.4 Avoid low-quality sources

Writing a successful is an art without strict rules. However, you should adapt your writing to the reader’s expectations, using appropriate arguments, graphs, tables, and references. By studying credible sources, you can learn proper practices and conventions. Unfortunately, many authors rely on low-quality work, resulting in a poorly written papers. Thus, consider the quality of the resources you read and cite very carefully. Avoid predatory journals and be cautious of information from online blogs, magazines, and other media without a peer-review process. Aim to find more reliable sources from reputable institutes with a reliable peer-review process and non-profit motivations. Do not simply rely on the first Google search result or the selection provided by Google Scholar, as listing there does not guarantee reliability or quality. Don’t cite articles and books published by vanity presses. Identifying predatory journals can be challenging, but there are some clear indicators of dubious quality. Here is a checklist to help determine if a source is valid:

- Listing in Beall’s List: Check if the journal or publisher is included in Beall’s List or on TUM’s website.

- Open-Access status: Determine if the paper or journal is open-access. If it is, consider who is financing the journal. Predatory journals often require authors to pay for publication, and their peer-review process is often questionable.

- Publisher reputation: Some large publishers serve as hubs for conferences and organizations to publish journals and articles. While a few journals from publishers like IEEE, ACM, scirp.org, SciEP, Science of Europe, and MDPI are of acceptable quality due to rigorous editorial standards, most journals are of low quality or predatory. Avoid these publishers or at least approach them with caution and consult your supervisor if in doubt.

- SJR ranking: Is the journal listed in the SCImago Journal Rank and how is their ranking?

- Questionable impact factor lists: Is the journal listed in dubious impact factor lists? The Scientific Jourrnal Impact Factor (sjifactor.com), for example, claims to determine the impact of a journal. However, the service provider remains anonymous, with no masthead, address or contact information other than an e-mail. This anonymity, which is against the law in many countries, including Europe, casts doubt on the quality and validity of the service, especially as the methodology is not transparent.

By following these guidelines, you can ensure that the sources you use and cite in your work are of high quality and reliability. However, note that there is no rule without an exception. For example, it can sometimes be appropriate to cite a post from an online blog. However, you should provide a clear reason for doing so. If you are uncertain, consult your supervisor.