2 Decision making basics

Section 11.2 of Saylor Academy (2002).

2.1 Definition: Decision

The statement of Eilon (1969) still holds true:

“An examination of the literature reveals the somewhat perplexing fact that most books on management and decision theory do not contain a specific definition of what is meant by a decision. One can find detailed descriptions of decision trees, discussions of game theory and analyses of various statistical treatments of payoffs matrices under conditions of uncertainty, but the definition of the decision activity itself is often taken for granted and is associated with making a choice between alternative courses of action.”

The word decision stems from the latin verb decidere which can have different meanings including

- make explicit,

- put an end to,

- bring to conclusion,

- settle/decide/agree (on),

- die,

- end up,

- fail,

- fall in ruin,

- fall/drop/hang/flow down/off/over,

- sink/drop,

- cut/notch/carve to delineate,

- detach,

- cut off/out/down,

- fell.

Wikipedia (2024) defines decision making as follows:

“In psychology, decision-making […] is regarded as the cognitive process resulting in the selection of a belief or a course of action among several alternative possibilities. Decision-making is the process of identifying and choosing alternatives based on the values, preferences and beliefs of the decision-maker. Every decision-making process produces a final choice, which may or may not prompt action. […] Decision-making can be regarded as a problem-solving activity yielding a solution deemed to be optimal, or at least satisfactory. It is therefore a process which can be more or less rational or irrational…”

Let’s agree on the following working definition that is symbolized in Figure 2.1:

Fitzgerald (2002, p. 8): “A decision is the point at which a choice is made between alternative—and usually competing—options. As such, it may be seen as a stepping-off point—the moment at which a commitment is made to one course of action to the exclusion of others.”

2.2 How to characterize decisions

Decision making is a process of investing time and effort to make a decision that leads to a results. Before we talk about the results, let’s discuss some (stereo) types of decisions that can help to design an appropriate decision making process. Using stereotypes and categorizations can be beneficial as they simplify complexities and provide guidance. For example, we often employ stereotypes to appropriately engage with others. When encountering a person dressed formally, it is generally advisable to approach them in a professional manner, even when uncertain of their preferences. In this case, our prior experiences help guide our behavior based on stereotypes.

According to Fitzgerald (2002, p. 9f) decisions can be roughly divided into two generic types:

- Routine decisions: Decisions that must be made at regular intervals.

- Non-routine: Unique, random, non-recurring decision situations.

Another common method of dividing decisions into two categories is as follows:

- Operative decisions: This type of decision usually involves day-to-day business operations. There is a lot of overlap with the routine category here. Examples of this type of decision include

- setting production levels,

- determining employee work shifts for the upcoming week to ensure adequate coverage,

- coordinating daily delivery routes for distributing products to customers,

- deciding to stop production or fix a problem if quality standards are not met during routine inspections, or, when it comes to decisions in our daily lives,

- where, what, when, and what to eat for lunch.

- Strategic decisions: These decisions typically concern long-term company policies and direction. Examples include

- entering a new market or exiting an industry,

- choosing a corporate design, or

- acquiring a competitor.

- In our personal lives, a strategic decision might be choosing between renting an apartment near the university or commuting from our parents’ home.

People often distinguish between decisions at work and private decisions. Private decisions affect fewer people on average, but usually the people involved are closer to you personally. However, both types of decisions involve the same things such as people (human resources), money (budgeting), buying and selling (marketing), how we do something (operations) or how we want to do it in the future (strategy and planning).

Some decisions are more important than others because the potential impact of a decision varies, that is, the scope of a decision. For example, decisions can affect one person or millions, one pound/dollar or millions, one product/service or an entire market, one day or ten years, etc.

However, it is not entirely clear how to validate the scope. It depends heavily on the perspective of the decision-maker. For a small company, for example, an investment of 10,000 euros may be a big decision, while for a multinational cooperation it is a drop in the ocean. So the scope for decisions is relative, not absolute. It depends entirely on the context in which the decision is made and on the characteristics of the person(s) making it.

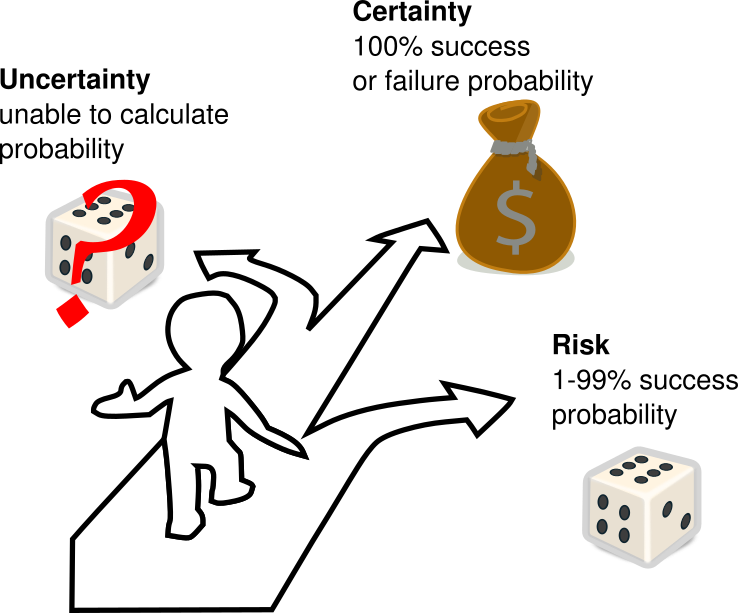

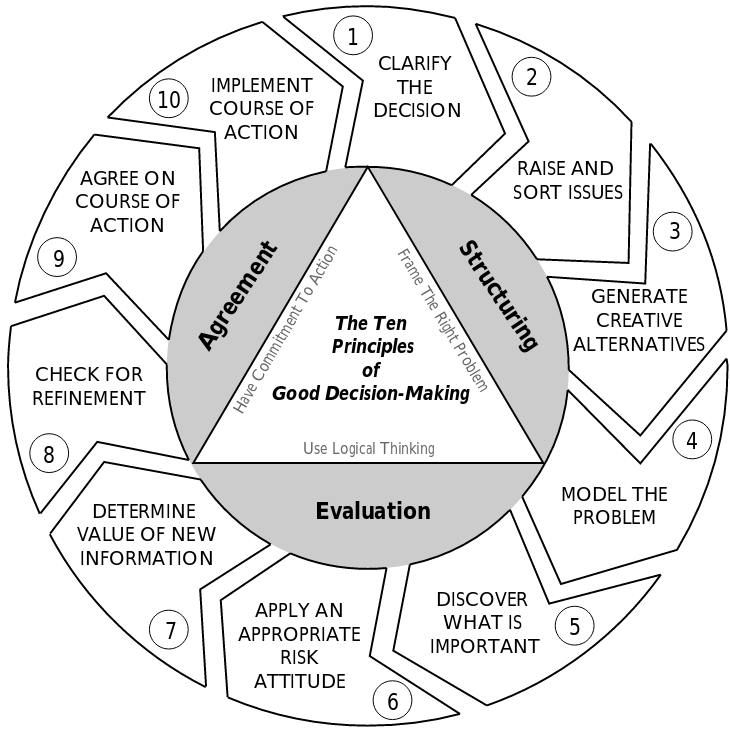

Source: CEOpedia (2021)

There are three general conditions (see Figure 2.7) that determine the design of the optimal decision making process:

Certainty: A condition under which taking a decision involves reasonable degree of certainty about its result, what are the opportunities and what conditions accompany this decision.

Risk: A condition under which taking a decision involves reasonable degree of certainty about its result, what are the opportunities and what conditions accompany this decision.

Uncertainty: A condition in which decision maker does not know all the choices, as well as risks associated with each of them and possible consequences.

2.3 Rationality

2.3.1 The rational model

A choice can be considered as a rational one when a individual decides for the best alternative courses of action. That is, the alternative with the greatest benefit over cost for the individual making the choice. Whatever the benefits and the costs maybe, a decision maker has to consider all and make a decision. Of course, in reality it is often difficult if not impossible to sum up benefits and costs as the nature of both may be totally different. That is what makes decision often so difficult.

The nature of costs and benefits is manifold and emotions in general are hard to quantify and take as a basis for a decision. To deal with that economists use a theoretical concept that measures everything in utility. That is a general and abstract measure to model worth or value. Its usage has evolved significantly over time. The term was introduced initially as a measure of pleasure or happiness within the theory of utilitarianism. For example, it represents the satisfaction or pleasure that people receive for consuming a bundle of goods and services.

The rational model assumes that actors always act in a way that maximizes their utility (as consumers) and profit (as producers) and that they are capable of arbitrarily complex considerations. This means that they consider all possible outcomes and choose the course of action that leads to the best result. In economics, this is known as the homo economicus assumption, which is a paraphrase of the assumption of perfect rationality. Of course, this assumption is highly idealized, and it is doubtful that any serious economist has ever believed it to be completely true in reality. It is important to understand the limitations of this assumption in order to make good decisions. Therefore, we will discuss the limitations in detail later. All in all, it is a useful assumption that is indispensable in theoretical research and simplifies many things in practical analysis. It makes it possible to make predictions and explain behavior to a certain extent.

Here is an example of a logical and systematic sequence of steps for making a decision, as outlined similarly by Fitzgerald (2002, p. 13):

Clearly identify the problem. A problem is defined as the perceived gap between the current situation and the desired outcome.

Generate potential solutions. For routine decisions, various alternatives can be easily identified using established decision rules. However, non-routine decisions require a creative process to discover new alternatives.

Select a solution. Using appropriate analytical approaches, choose the alternative with the highest expected value. In decision theory, this is referred to as maximizing the expected utility of the outcomes.

Implement the solution. Successful implementation requires ensuring that those responsible understand and accept their roles, and have the necessary motivation and resources for success.

Evaluate and improve. Assess the effectiveness of the decision and refine the process for future improvements.

2.3.2 Irrationality

While the rational model is useful, it can also be criticized in a number of ways. One key misconception is that managers always optimize their decisions through rationality, consciously selecting and implementing the best alternatives. However, this belief rests on several questionable assumptions, as outlined by Fitzgerald (2002, p. 13):

- It is rarely possible to know in advance all possible alternative solutions and predict their specific outcomes.

- The assumption that there is always an optimal solution among the identified alternatives may not hold true.

- Accurately and numerically weighting the alternatives, their outcome probabilities, and the relative desirability of these outcomes is often impractical.

- Decision-makers are not always purely rational; emotions, biases, and organizational politics frequently influence the process.

- Business decisions are not exclusively driven by the desire to maximize profits.

The rational model is considered normative because it prescribes a strict, logical sequence of steps to follow in any decision-making process. It is based on the assumption that human behavior is logical and therefore predictable in certain conditions. However, this doesn’t always reflect real-world decision-making. For example, findings from behavioral economics reveal that the concept of homo economicus, while useful, is flawed in several key aspects.

After all, what would happen if economics adopted the opposite extreme, assuming individuals act irrationally? If actors behaved randomly and unpredictably, we would struggle to make any predictions, and the future would resemble a random walk. Science itself would become meaningless and unnecessary.

Clearly, the extreme of irrationality isn’t a viable alternative. So, what can we do? We can identify, explain, and account for the limitations of the homo economicus assumption in both theory and empirical analysis. Economists, and anyone applying or studying economic theories, should be aware of the pitfalls in human decision-making and recognize that our ability to act rationally is often limited.

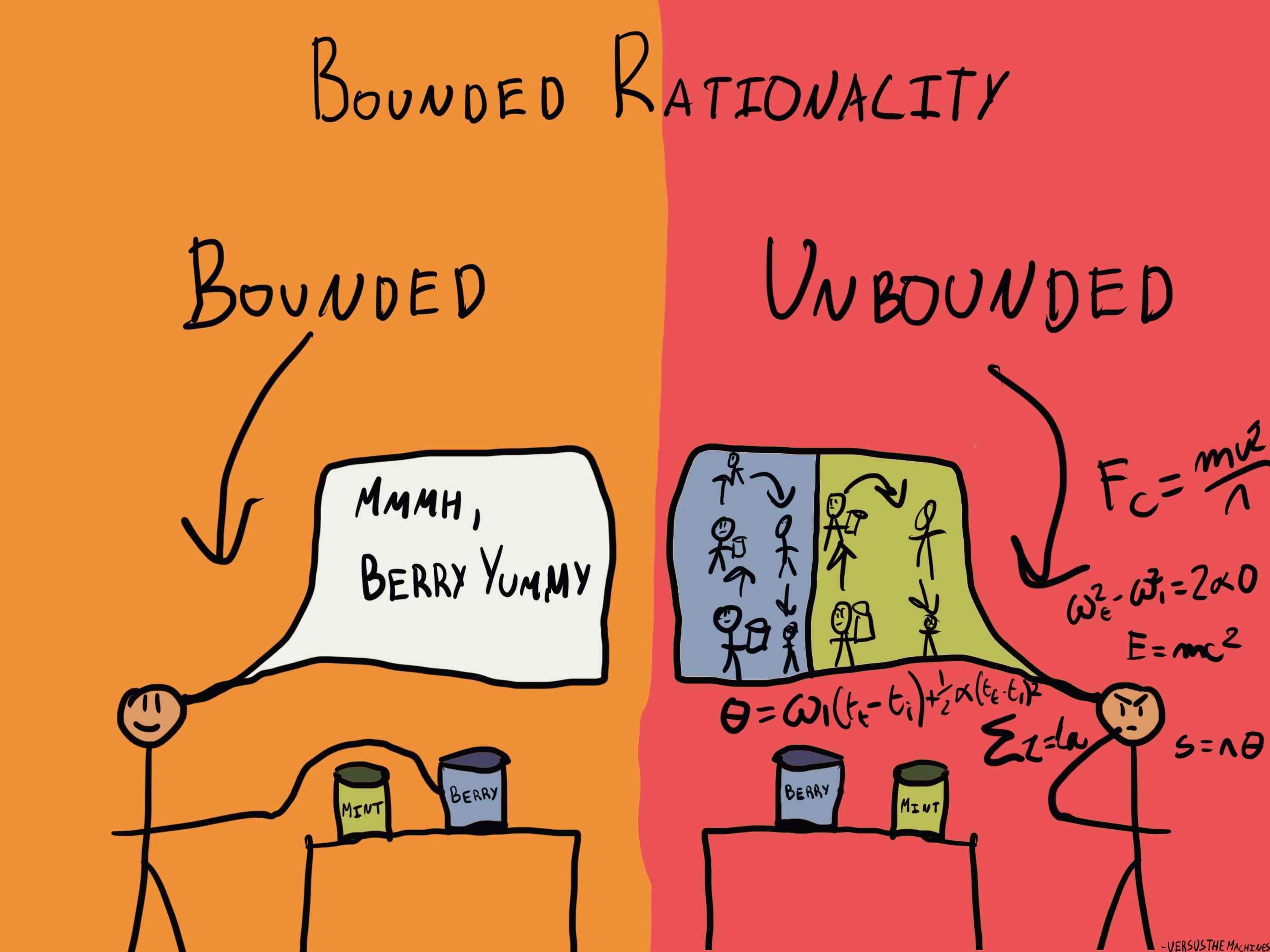

2.3.3 Bounded rationality

Source: Picture is taken from Nobel Foundation archive.

Herbert A. Simon (1916-2001) shown in figure Figure 2.8 received the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences in 1978 and the Turing Award1 in 1975. According to NobelPrize.org (2021), he

1 The Turing Award is an annual prize given by the Association for Computing Machinery (ACM) for contributions of lasting and major technical importance to the computer field. It is generally recognized as the highest distinction in computer science and is known as or often referred to as `Nobel Prize of Computing’.

“combined different scientific disciplines and considered new factors in economic theories. Established economic theories held that enterprises and entrepreneurs all acted in completely rational ways, with the maximization of their own profit as their only goal. In contrast, Simon held that when making choices all people deviate from the strictly rational, and described companies as adaptable systems, with physical, personal, and social components. Through these perspectives, he was able to write about decision-making processes in modern society in an entirely new way”.

In particular, he proposed bounded rationality as an alternative basis for the mathematical and neoclassical economic modelling of decision-making, as used in economics, political science, and related disciplines.

Bounded rationality proposes that decision making is constrained by managers’ ability to process information, i.e., the rationally is bounded (see figure Figure 2.9). Managers use shortcuts and rules of thumb which are based on their prior experience with similar problems and scenarios. Given the constraints of managers in their position, they do not actually optimize their choice given the available information. It is more like finding a satisfactory solution, not necessarily the best or the optimal solution.

2.3.4 Heuristics

In real life, we frequently rely on heuristics to solve problems and make decisions. A heuristic is any approach to solving a problem that uses a practical method that is not guaranteed to be optimal, perfect, or rational. However, a heuristic should–at best–be sufficient to achieve an immediate, short-term goal or approximation. Overall, people use heuristics because they either cannot act completely rationally or want to act rationally but do not have the time it would take to compute the perfect solution. Moreover, the effort is probably not worth it or simply not possible given the time constraints under which the problem must be solved. A heuristic is a mental shortcut or rule of thumb to make decisions and solve problems quickly and efficiently. It helps individuals to arrive at a solution without extensive analysis or evaluation of all available information. Heuristics are usefull when time, resources, or information are limited.

While heuristics can be helpful in many situations, they can also lead to errors and biases, particularly when they are overused or misapplied. We will discuss some of these biases in Chapter 11 in greater detail.

2.3.5 System 1 and System 2 Thinking

In fact, many studies have proven that people often do not act as predicted by theories that assume a home economicus. These behavioral economic research studies the effects of psychological, cognitive, emotional, cultural and social factors on the decisions of individuals and institutions and how those decisions vary from those implied by classical economic theory. While we will discover some more details about it in Chapter 11, I recommend watching the following video about the work of Tversky and Kahneman’s work

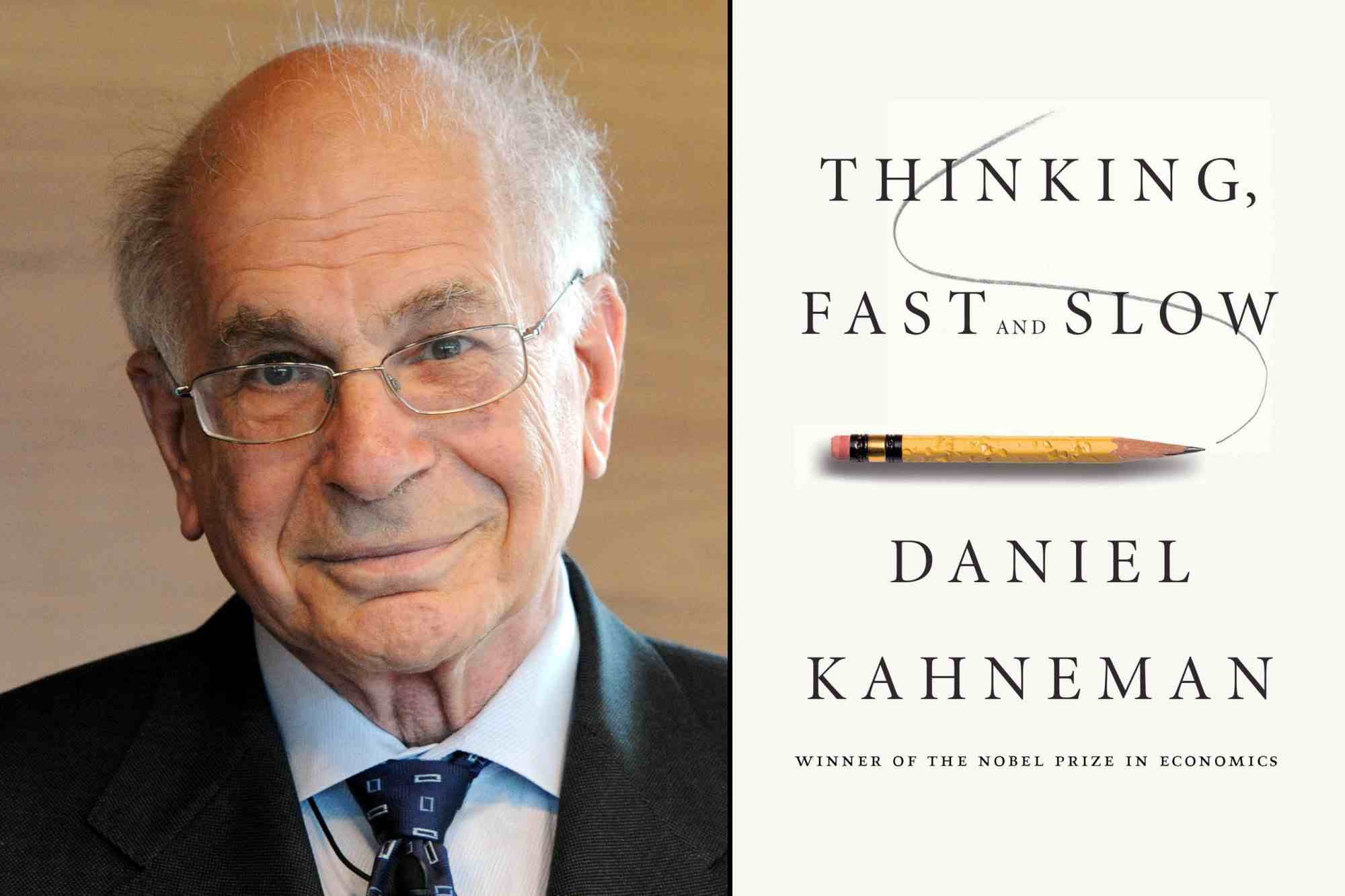

The Nobel prize winner Daniel Kahneman (1934 - 2024) is probably the most well-known figure of behavioral economics (see Figure 2.11). One reason is his best-selling book Thinking Fast and Slow where he summarizes his work for a broader audience and introduced the modes of System 1 and System 2 thinking. These two modes are easy to understand and often helpful. Here is a video where he describes these two modes in his own words.

System 1 thinking refers to our intuitive system, which is typically fast, automatic, effortless, implicit, and emotional. We make most decisions in life using this mode of thinking. For instance, we usually decide how to interpret verbal language or visual information automatically and unconsciously.

By contrast, System 2 refers to reasoning that is slower, conscious, effortful, explicit, and logical. In most situations, our System 1 thinking is quite sufficient; it would be impractical, for example, to logically reason through every choice we make while shopping for products in our daily life. But System 2 logic should preferably influence our most important decisions. The busier and more rushed people are, the more they have on their minds, and the more likely they are to rely on System 1 thinking. In fact, the pace of managerial life suggests that executives often rely on System 1 thinking. Although a complete System 2 process is not required for every managerial decision, a key goal for managers should be to identify situations in which they should move from the intuitively compelling System 1 thinking to the more logical System 2.