Appendix A — Microeconomic preliminaries

Before starting discussing production and consumption, we should first define what (micro)economist mean when they speak of firms and consumers.

A firm is a productive unit. In particular, it is an organization that produces goods and services, called the output. To do so, it uses inputs called factors of production: labor, capital, land, skills, etc. The relationship between the inputs and the output is the production function. The goal of the firm is to achieve whatever goal its owner(s) decide to achieve. Usually, it is (and in Germany, for example, it has to be the case by law) to generate profits, that is, total revenue minus total cost for the level of production. Determining the optimal level of production for a firm is a multifaceted decision that encompasses various strategic aspects and is heavily influenced by the market situation of firms. This includes factors such as market power, demand function, production function, cost function, and revenue function.

A consumer is an individual that purchases goods or services to satisfy their needs. They make decisions regarding what to buy, how much to buy in order to maximize their utility. Microeconomists study consumer behavior and factors that influence it, such as prices, income, preferences, and market conditions, to understand the choices consumers make and their impact on markets and the overall economy.

A.1 Production functions

A firm or a company is a productive unit. In particular, it is an organization that produces goods and services. In short, it can be called output. To do so, it uses inputs called factors of production, that is, labor, capital, land, skills, etc. The relationship between the inputs and the output is the production function. The goal of the firm is to achieve whatever goal its owner(s) decide to achieve through the firm. Usually, it is (and in Germany for example it has to be the case by law) to generate profits, that is, total revenue minus total cost for the level of production.

A production function (PF) is a mathematical representation of the process that transforms inputs into output.

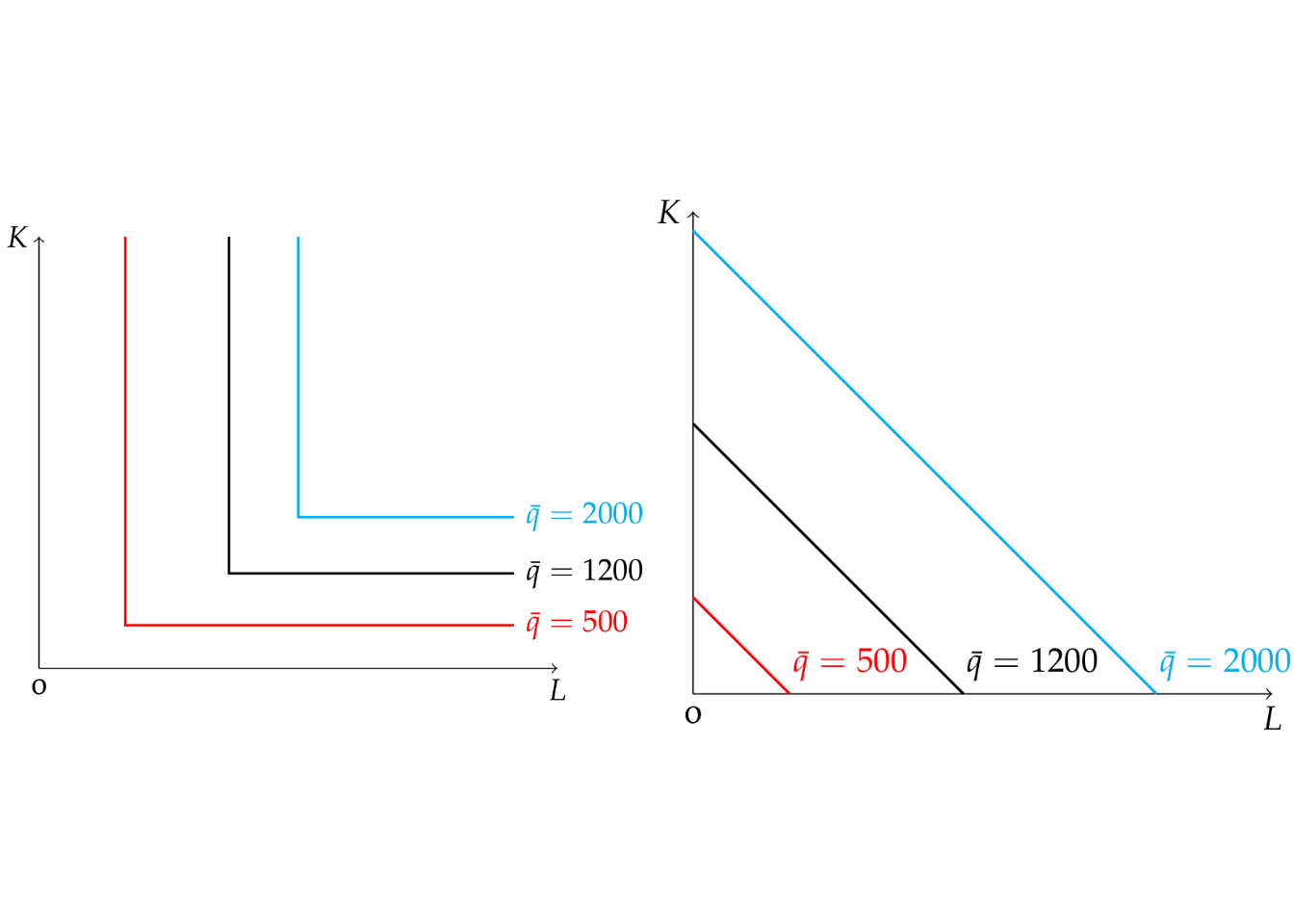

- When factors of production are perfect substitutes the PF can be written like this: \[ q=f(K,L)=L+K \]

- When factors of production are perfect complements the PF can be written like this: \[ q=f(K,L)=\min (L,K) \]

- A special and often used function is the Cobb-Douglas PF: \[ q=f(K,L)=K^\alpha L^{1-\alpha} \quad \text{with} \quad 0<\alpha<1 \]

The returns to scale describes the increase in output when a firm multiples all of its inputs by some factor. Let \(\lambda>1,\) then, with two factors \(\mathrm{K}\) and \(L\), we can define that for \[ f(c K, c L)= c^\lambda f(K, L), \]

- \(\lambda>1\) the PF has increasing returns to scale,

- \(\lambda=1\) the PF has constant returns to scale,

- \(\lambda<1\) the PF has decreasing returns to scale.

The marginal product is the change in the total output when the input varies of one infinitesimal small unit. Graphically, the marginal product is the slope of the total product function at any point. The slope of the total product function, that is, the marginal product, is generally not constant. The marginal product to an input is assumed to decrease beyond some level of input. This is called the law of diminishing marginal returns. In particular, we can distinguish:

- positive marginal returns when \(f'>0\) and

- diminishing marginal returns when \(f''<0\) and

- increasing marginal returns when \(f''>0\).

A.2 Production possibility frontier curve

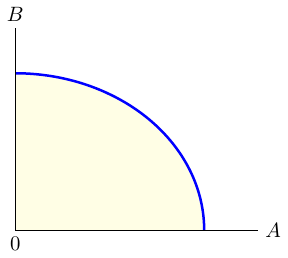

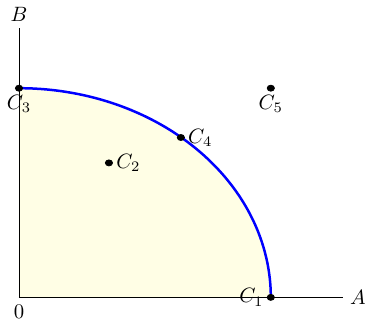

The production possibilities frontier (PPF) curve shown in Figure A.1 provides a graphical representation of all possible production options for two products when all available resources and factors of production are fully and efficiently utilized within a given time period. The PPF serves as a boundary between combinations of goods and services that can be produced and those that cannot.

The PPF is an invaluable tool for illustrating the effects of scarcity as it provides insights into production efficiency, opportunity costs and the trade-offs between different choices. In general, the PPF exhibits concavity, as not all factors of production can be used equally productively in all activities.

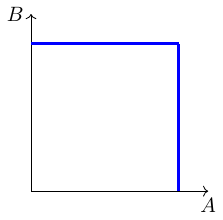

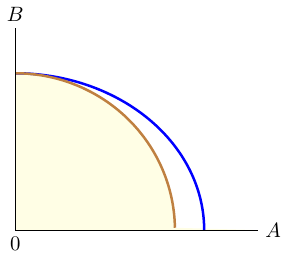

Economic growth refers to the continuous expansion of production possibilities. An economy experiences growth through technological advances, improvements in the quality of labor or an increase in the factors of production (labor, capital). When the resources of an economy increase, the production possibilities also expand, shifting the PPF outwards. It is worth noting that PPF can be used to explain production in an economy or company.

Production efficiency occurs when it is impossible to produce more of one good or service without producing less of another. If production takes place directly on the PPF, this means efficiency. If, on the other hand, production takes place within the PPF (yellow shaded area of Figure A.1), it is possible to produce more goods without sacrificing existing goods, which indicates inefficiency. If production is on the PPF, there is a trade-off, as obtaining more of one good requires sacrificing a certain amount of another good. This trade-off is associated with costs called opportunity costs.

A.3 Indifference curves and isoquants

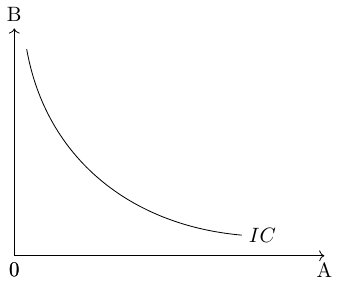

Combinations of two goods that yield the same level of utility for consumers are represented by indifference curves, see figure Figure A.5. These curves illustrate the various bundles of goods where consumers are equally satisfied. That means all points on an indifference curve represent the same level of utility. The shape of the indifference curve is determined by the underlying utility function, which captures the preferences of consumers for consuming different combinations of the two goods.

The slope of an indifference curve indicates the rate at which the two goods can be substituted while maintaining the same level of utility for the consumer. Technically, the slope represents the marginal rate of substitution, which is equal to the absolute value of the slope. It measures the maximum quantity of one good that a consumer is willing to give up in order to obtain an additional unit of the other good.

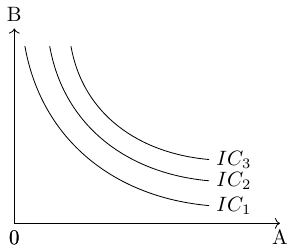

It is assumed that consumers aim to attain the highest possible indifference curve because a higher curve, located further to the right on a coordinate system, represents a higher level of utility. In Figure A.6, for example, \((IC_1)\) represents a lower level of utility than \((IC_2)\).

Similar to the concept of indifference curves, an isoquant shows the combinations of factors of production that result in the same quantity of output.

A.4 Budget constraint

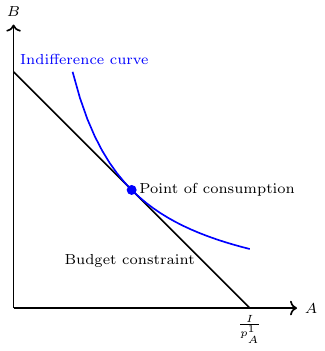

In microeconomics, the concept of a budget constraint plays a vital role in understanding consumer decision-making and helps to analyze consumer choices and trade-offs. The budget constraint represents the limitations faced by consumers in allocating their limited income across different goods and services. The budget constraint indicates that the total expenditure on goods and services, calculated by multiplying the prices of each item by its corresponding quantity, must be less than or equal to the consumer’s income. Mathematically, the budget constraint can be expressed as: \[ P_1 \cdot Q_1 + P_2 \cdot Q_2 + \ldots + P_n \cdot Q_n \leq I \] where (\(P_n\)) represent the prices of goods, (\(Q_n\)) denote the quantities of goods (\(n\)) consumed. (\(I\)) denotes the consumer’s income or their budget.

Consumers strive to maximize their utility by selecting the optimal combination of goods and services within the constraints imposed by their limited income. This involves making decisions about how much of each good to consume while staying within the budgetary limits. The graphical representation of the ideal consumption point is depicted in Figure Figure A.8.

By studying the budget constraint, economists can gain insights into consumer behavior, price changes, and the impact of income fluctuations on consumption patterns.