31 Balance of payments

Required readings: Council of Economic Advisers (2004, ch. 14)

31.1 Introduction

The Balance of Payments is a record of a country’s financial transactions with the rest of the world. It tracks the money flowing in and out through various economic activities. If we account for all transactions, the inflow and outflow should theoretically balance. Before I elaborate on this concept, let’s clarify some key terms:

- Exports: Goods and services sold to other countries.

- Imports: Goods and services bought from other countries.

- Trade balance: The difference between the value of goods and services a country sells abroad and those it buys from abroad, also known as net exports.

- Trade surplus: When a country sells more than it buys, resulting in a positive trade balance.

- Trade deficit: When a country buys more than it sells, leading to a negative trade balance.

- Balanced trade: When the value of exports equals imports.

- Net capital outflow: The difference between the purchase of foreign assets by domestic residents and the purchase of domestic assets by foreigners. This equals net exports, indicating that a country’s savings can fund investments domestically or abroad. We will elaborate on that later on in greater detail.

31.2 The payments must be balanced!

Every international financial transaction is essentially an exchange. When a country sells goods or services, the buying country compensates by transferring assets. Consequently, the total value of goods and services a country sells (its net exports) must be equal to the value of assets it acquires (its net capital outflow).

The Balance of Payments account consists of two primary components:

The Current account (Leistungsbilanz) measures a country’s trade balance (goods and services exports minus imports) plus the effects of net income and direct payments. It is positive, if a country is a net lender to the rest of the world and negative, if it is a net borrower from the rest of the world. In other words, an account surplus increases a country’s net foreign assets.

The Capital account (Kapitalbilanz) reflects the net change in ownership of national assets. Capital can flow in the form of following:

- Foreign Direct Investment (FDI): It involves investing in foreign companies with the intention of controlling or significantly influencing their operations.

- Foreign Portfolio Investment (FPI): This type of investment is in foreign financial assets, such as stocks and bonds, where the investor does not seek control over the companies.

- Other investments: This includes capital flows into bank accounts or funds provided as loans. It also encompasses the reserve account, which is managed by the central bank responsible for buying and selling foreign currencies.

Ignoring statistical effects, these two subaccounts must sum to zero. Table 31.1 shows you a hypothetical balance of payment account.

| Receipt (credit) | Payments (debits) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Current Account | |||

| 1. Export of goods and services | 800 | 3. Import of goods and services | 600 |

| 2. Unilateral receipts | 300 | 4. Unilateral payments | 390 |

| Total | 1100 | Total | 990 |

| Capital Account | |||

| 5. Borrowings | 700 | 7. Lendings | 750 |

| 6. Sale of gold/assets | 100 | 8. Purchase of gold/assets | 150 |

| Total | 800 | Total | 900 |

| Errors and omissions | 10 | ||

| Total | 1900 | Total | 1900 |

While it’s true that the overall totals of payments and receipts must inherently balance, certain transaction types can create imbalances, leading to either deficits or surpluses. These imbalances may manifest in various sectors such as trade in goods (commodities), services trade, foreign investment income, unilateral transfers (including foreign aid), private investment, and the flow of gold and currency between central banks and treasuries, among other international dealings. It’s crucial to note, though, that the accounting framework ensures these surpluses and deficits ultimately zero out, adhering to the principles of double-entry bookkeeping.

31.3 A normative discussion of imbalances in the capital and current account

Normatively discussing imbalances in the capital and current accounts of countries involves evaluating these phenomena from a perspective of what ought to be, considering ethical, practical, and policy implications. These imbalances are not merely numerical figures; they reflect underlying economic activities and policy decisions with significant implications for national and global economic health.

31.3.1 Current account imbalances

The current account includes trade in goods and services. A surplus in the current account indicates that a country is exporting more goods than it imports.

Surpluses: Normatively, persistent current account surpluses might be viewed as a sign of a country’s competitive strength in the global market. However, they can also indicate underconsumption or insufficient domestic investment, suggesting that a country is not fully utilizing its economic resources to improve the living standards of its population. Furthermore, large surpluses can lead to tensions with trading partners and might prompt accusations of unfair trade practices or currency manipulation.

Deficits: On the other hand, persistent deficits could signal domestic economic vitality and an attractive environment for investment, reflecting high consumer demand and robust growth. Yet, they can also indicate structural problems, such as a lack of competitiveness, reliance on foreign borrowing to sustain consumption, or inadequate savings rates. Over time, large deficits may lead to unsustainable debt levels, making the country vulnerable to financial crises.

31.3.2 Capital account imbalances

The capital account records the net change in ownership of national assets. It includes the flow of capital into and out of a country, such as investments in real estate, stocks, bonds, and government debt.

Inflows: Capital account inflows can signify strong investor confidence in a country’s economic prospects, potentially leading to increased investment and growth. However, excessive short-term speculative inflows can destabilize the economy, leading to asset bubbles and subsequent financial crises when the capital is suddenly withdrawn.

Outflows: Capital outflows might indicate a lack of confidence in the domestic economy or better opportunities abroad. While some level of outflow is normal for diversified investment portfolios, large and rapid outflows can precipitate a financial crisis by depleting foreign reserves and putting downward pressure on the currency.

31.4 A formal representation

In the following, I present a streamlined perspective on the global trading system. This overview does not engage with the benefits or drawbacks of maintaining trade surpluses or deficits, a subject that warrants its own discussion. However, it aims to identify the factors influencing current account deficits and surpluses.

31.4.1 Closed economy

Within a closed economy, we identify three principal actors: households, firms, and the government. Let’s define \(C\) as the consumption of goods and services by households, encompassing necessities and luxuries like food, housing, and entertainment. Let \(G\) represent government expenditures, which cover infrastructure, social services, military outlays, education, and more. Lastly, \(I\) symbolizes the investment by firms in assets such as machinery, buildings, and research and development. Given these components, the total economic output, \(Y\), can be expressed by the fundamental equation of economics as:

\[ Y = C + I + G. \]

This equation encapsulates the aggregate spending within a closed economy, highlighting the interplay between consumption, investment, and government expenditure in determining overall economic activity.

If we define national savings, \(S\), as the share of output not spent on household consumption or government purchases, then the investments, \(I\), must be equal to the savings in a closed economy: \[\begin{align*} Y &= C + I + G\\ \Leftrightarrow \underbrace{Y - C - G}_S &= I \\ \Leftrightarrow S &= I, \end{align*}\]

This implies that within a closed economy, any portion of the output that is not consumed—either privately by households (\(C\)) or by the government (\(G\))—necessarily must be allocated towards investment (\(I\)). Thus, the equation underscores a foundational economic principle: the total output of an economy (\(Y\)) is either consumed or invested, leaving no surplus output.

31.4.2 Open economy

In an open economy, the dynamics of household consumption, government expenditures, and firm investments extend beyond domestic production to include imports from and exports to foreign markets. Thus, an economy can import and export goods. Denoting imports by \(IM\) and exports by \(EX\), we can re-write the fundamental equation of economics by adding the concept of net exports (\(NEX\)), the difference between a country’s exports and imports. A positive net export value (\(EX > IM\)) indicates a trade surplus, reflecting that the economy exports more than it imports. Conversely, a negative net export value (\(EX < IM\)) signifies a trade deficit, where imports exceed exports:

\[\begin{align*} Y &= C + I + G + \underbrace{EX - IM}_{NEX}\\ \Leftrightarrow \underbrace{Y - C - G}_S &= I + NEX\\ \Leftrightarrow \underbrace{S-I}_{NCO} &= NEX \end{align*}\]

In scenarios where investment equals savings (\(I = S\)), the economy’s net exports are zero, reflecting a balance between domestic production not allocated towards household or government consumption and investments. However, when an economy experiences a trade surplus (\(NEX > 0\)), such as Germany in recent decades, it implies that domestic savings exceed investments. This surplus indicates that the country produces more than it spends on domestic goods and services, channeling excess savings into investments abroad. Thus, savings not utilized domestically (\(S - I\)) are equivalent to the net capital outflow (\(NCO\)), establishing a direct link between a country’s trade surplus and its role as a global lender or investor:

\[ NCO = NEX \]

Net exports must be equal to net capital outflow

The accounting identities above simply state that there is a balance of payments. The Balance of Payment accounts are based on double-entry bookkeeping and hence the annual account has to be balanced. If an economy has a current account trade deficit (surplus), it is offset one-to-one by a capital account surplus (deficit) to assure a balance of payments. In other words, if an economy wants to import more goods than it produces, it must attract foreign capital to be invested at home.

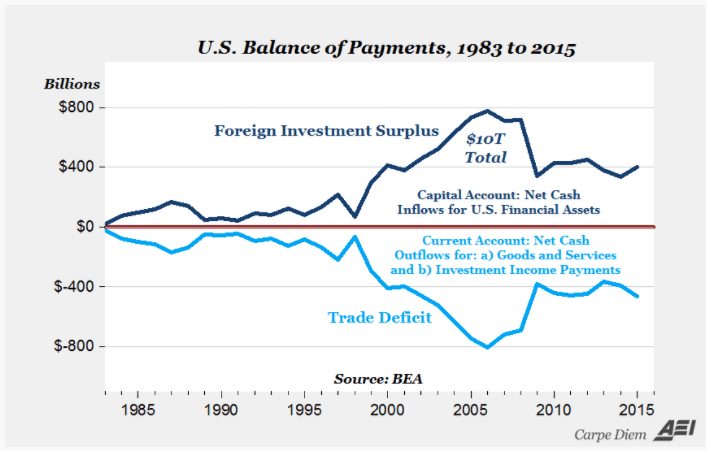

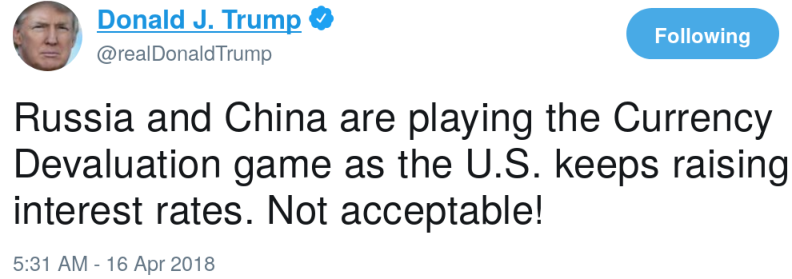

31.5 Case study: U.S. trade deficit

Consider a scenario where the United States is unable to attract sufficient capital flows from abroad to finance its trade deficit. In such a case, American consumers continue purchasing foreign goods with US Dollars, leading to an outflow of US Dollars that surpasses inflow. This imbalance results in an increased supply of US Dollars relative to its demand, causing the value of the US Dollar to depreciate. A depreciated US Dollar would, in theory, make US exports more competitive (cheaper for foreign buyers) and imports more costly, thereby potentially reducing the current account deficit. However, the trade deficit of the United States has remained relatively stable, and the US Dollar has not experienced significant depreciation. This stability is partly why former President Trump criticized other countries for allegedly manipulating their currencies, see Figure 31.2.

As Trump thinks a trade deficit is bad for the United States, he would like to have a weak dollar and low interest rates. He advocated for a weaker dollar (I guess he would never express it like that) and lower interest rates to address this issue. A weaker dollar would render American products more affordable internationally, stimulating exports and discouraging imports. Concurrently, lower interest rates in the United States would diminish the country’s appeal for foreign capital investments (\(I\) would decrease), leading to reduced net capital inflows. This adjustment would, in turn, decrease the Capital Account surplus and, by extension, shrink the Current Account deficit. Specifically, Trump accused the Chinese government and the European Central Bank of implementing policies that undervalue their currencies (the Renminbi and the Euro), thereby gaining an unfair advantage in trade.

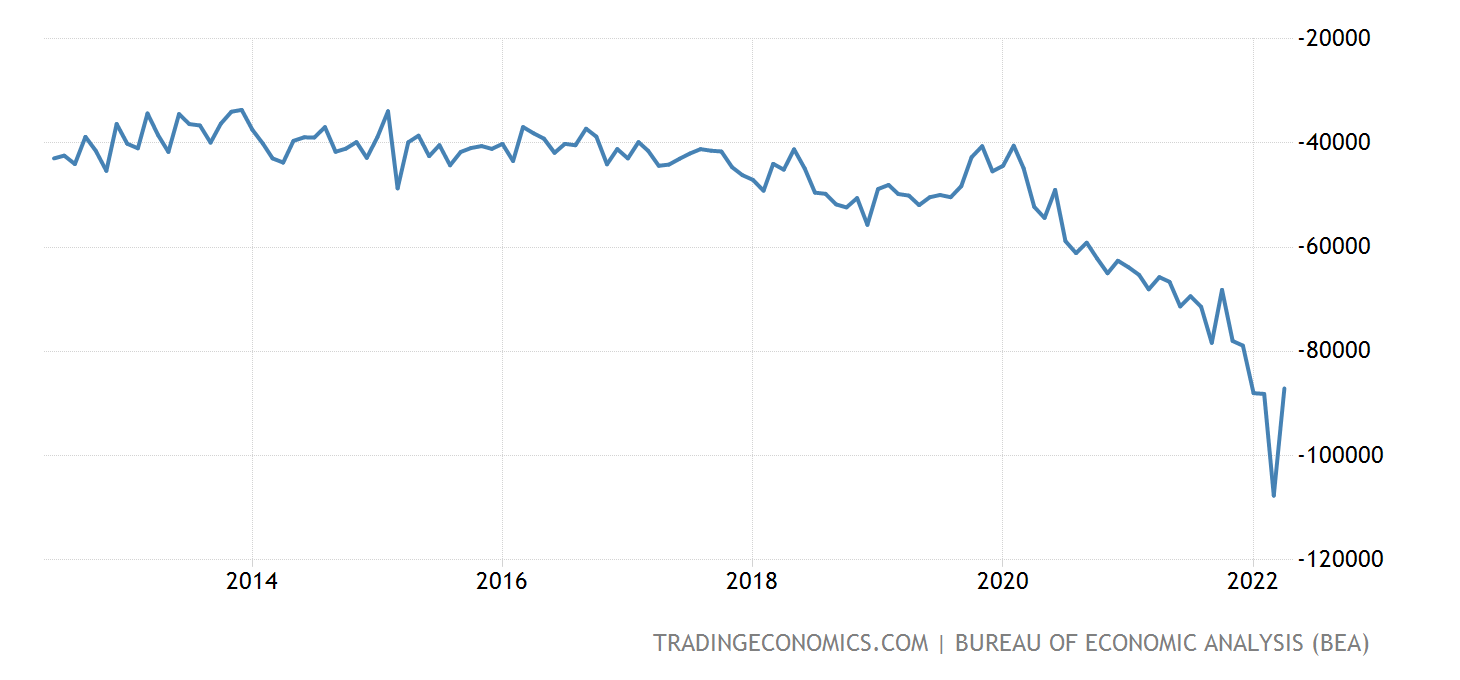

Despite significant efforts by President Trump to reduce the U.S. trade deficit, the endeavor did not achieve its intended outcome, as illustrated in Figure 31.3. One likely reason for this shortfall was the reduction of taxes for large corporations, which enhanced the rate of return on investments. This policy made investing in the U.S. more appealing to foreign investors, potentially counteracting efforts to diminish the trade deficit.