23 Unemployment and business cycles

Required readings:

D. Shapiro et al. (2022, ch. 14)

Learning objectives:

Students will be able to:

- that the gap between actual GDP and potential GDP is a key measure of the economy’s performance in the short run.

- the causes of unemployment.

- what the reverse multiplier effect is.

- the role of wage-setting for the aggregate economy.

23.1 Unemployment

Unemployment poses a significant challenge both personally and socially, leading to the loss of income for individuals and a reduction in national production. The individual costs of unemployment are multifaceted and include the loss of earnings, increased risk of falling into poverty, and deterioration of health. Furthermore, unemployment can result in negative social behaviors, such as drug and alcohol abuse, crime, and the de-skilling of workers who become disconnected from evolving work practices and technology. Persistently high unemployment can severely undermine an individual’s future job prospects by depleting their human capital.

For an economy unemployment simply means that there are production factors, that is, labor, unutilized. That comes along with lower tax revenues and increased welfare payments. Additionally, unemployment contributes to a range of social costs, including deteriorating health, rising crime rates, social unrest, and political repercussions.

In any economy, adults fall into one of three categories: they can be employed, unemployed, or not participating in the labor force. Unemployment is usually defined as the condition of being jobless while being willing and able to work. It’s important to note that this definition can vary from country to country and among different federal statistical agencies.

To combat unemployment, various government programs can be implemented to help unemployed workers find new jobs more efficiently. These programs include active labor market policies often run by employment agencies such as training and educational initiatives. Other passive labor market policies such as wage subsidies, public employment schemes, and unemployment benefits can also help to improve the labor market. Each of these measures aims to reduce the duration and impact of unemployment, fostering a more robust and productive workforce.

23.1.1 Explanations for unemployment

In a perfect labor market, wages would adjust so that the quantity of labor supplied equals the quantity of labor demanded. At equilibrium, there is no unemployment, and wage rate adjustments ensure that all workers are fully employed. However, the reality is that labor markets do not clear instantaneously.

Job losses within specific industries may result from technological change, which forces workers whose knowledge, skills, and experience have become redundant to seek new employment. Additionally, structural changes in the economy can affect its makeup over time. Such changes may stem from competition from abroad, technological advancements, or shifts in societal norms and trends. Consequently, workers who lose their jobs in one industry often encounter available positions that require skills they do not possess, a situation commonly referred to as occupational immobility. They may also find that potential job opportunities are located outside their immediate region, known as geographic immobility.

Furthermore, wages may be set too high for labor demand to absorb all available labor supply. This scenario can occur due to several factors that create above-equilibrium wages, including minimum wage laws, the influence of unions, and efficiency wages.

When wages exceed the equilibrium level, the quantity of labor supplied surpasses the quantity of labor demanded, resulting in unemployment as workers wait for job openings to become available. There are three rational explanations for wages above the market-clearing level.

Minimum wage

When the minimum wage is set above the level that balances supply and demand, it creates unemployment. Minimum wages often have the most significant impact on the least skilled and least experienced members of the labor force, such as teenagers.

Unions

Source: Labor Union Report

A union is a worker association that bargains with employers over wages and working conditions, see Figure 23.1. In the early 1980s, over half of the UK labor force was unionized; however, this figure rapidly fell to a union coverage of 25.4% in 2013. The process where unions and firms agree on the terms of employment is called collective bargaining. Economists have found that union workers typically earn significantly more than similar workers who do not belong to unions. A strike may be organized if the union and the firm cannot reach an agreement; this refers to the union organizing a withdrawal of labor from the firm.

Are unions good or bad for the economy?

Critics argue that unions cause an inefficient and inequitable allocation of labor. Wages above the competitive level reduce the quantity of labor demanded, resulting in unemployment where some workers benefit at the expense of others. On the other hand, advocates contend that unions are a necessary antidote to the market power of firms hiring workers, especially in the presence of local monopsonies. Furthermore, they argue that unions play a critical role in helping firms respond efficiently to workers’ concerns.

Efficiency wages

Efficiency wages are above-equilibrium wages paid by firms with the aim of increasing worker productivity. The theory of efficiency wages posits that firms operate more efficiently if wages are set above the equilibrium level. Nobel Prize-winning economist Joseph E. Stiglitz, recognized for his work on asymmetric information and efficiency wages, has contributed significantly to this theory (C. Shapiro & Stiglitz, 1984). A firm may prefer to offer higher than equilibrium wages for several reasons. First, higher wages can lead to improved worker health, as better-paid employees tend to maintain a healthier diet, which can enhance productivity. Second, higher wages reduce worker turnover because employees earning more are less likely to seek alternative job opportunities. Third, better pay motivates workers to exert more effort, leading to increased productivity. Lastly, higher wages attract a more qualified pool of applicants, fostering a stronger workforce.

23.1.2 Types of unemployment

Frictional unemployment

Frictional unemployment arises from normal labor turnover. These workers are searching for jobs. The unemployment related to this search process is a permanent phenomenon in a dynamic, growing economy. Frictional unemployment increases when more people enter the labor market or when unemployment compensation payments increase.

- It takes time for workers to search for jobs that best suit their tastes and skills.

- Search unemployment is inevitable because the economy is always changing.

- Workers in declining industries will find themselves looking for new jobs, and firms in growing industries will be seeking new workers.

- If job search takes time, this means there must always be some unemployment.

Structural unemployment

Structural unemployment arises when changes in technology or international competition change the skills needed to perform jobs or change the locations of jobs. Sometimes there is a mismatch between skills demanded by firms and skills provided by workers, especially when there are great technological changes in an industry. Structural unemployment generally lasts longer than frictional unemployment. Minimum wages and efficiency wages create structural unemployment.

Voluntary and involuntary unemployment

Voluntary unemployment occurs if people choose to remain unemployed rather than taking jobs that are available. Involuntary unemployment occurs if people want to work at prevailing market wages but cannot find employment.

Cyclical unemployment

Cyclical unemployment is the fluctuating unemployment over the business cycle. It increases during a recession and decreases during an expansion.

Natural unemployment

Natural unemployment arises from frictions and structural change when there is no cyclical unemployment—when all the unemployment is frictional and structural. As a percentage of the labor force, it is called the natural unemployment rate.

Full employment

Full employment is defined as a situation in which the unemployment rate equals the natural unemployment rate.

23.2 Business cycles

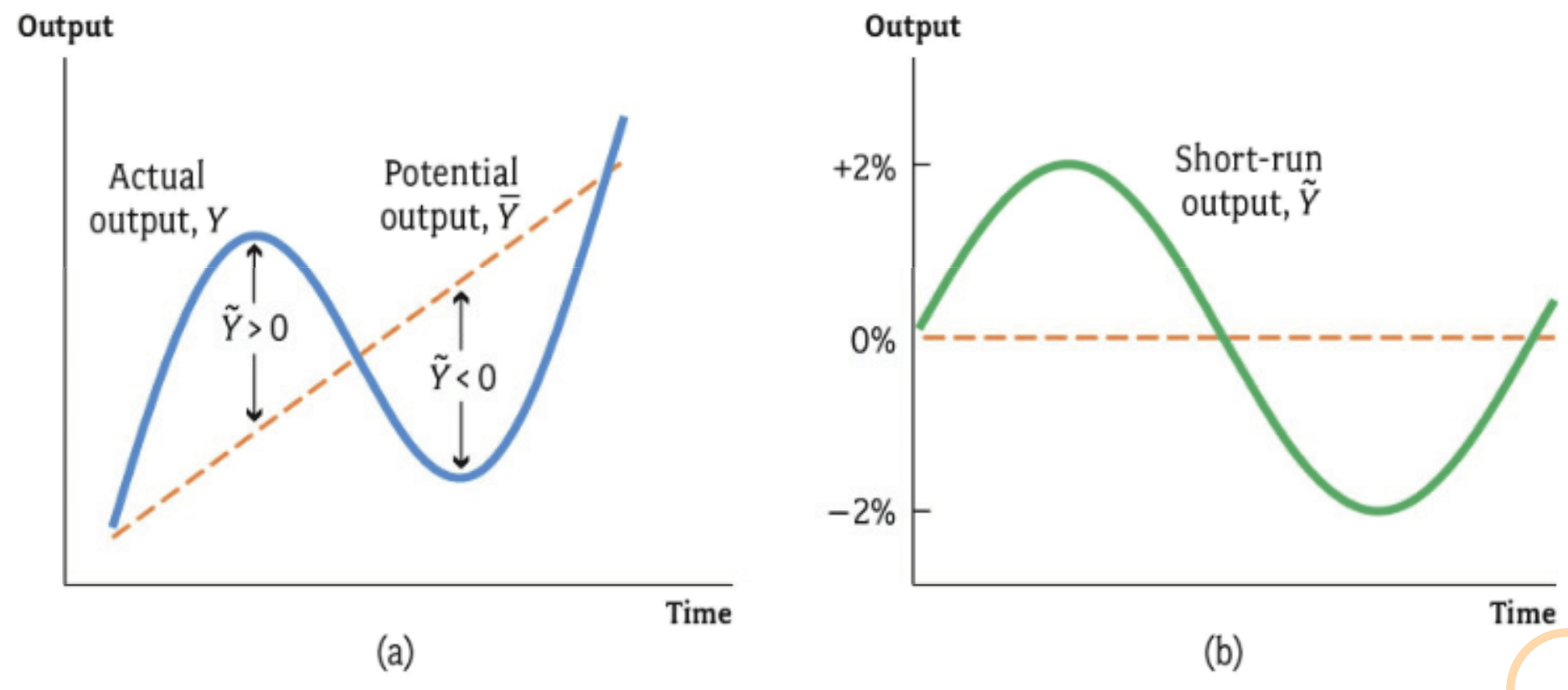

Source: Jones (2008, p. 220)

Actual output in an economy is the sum of the long-run trend and short-run fluctuations (see Figure 23.4):

\[ \underbrace{\textnormal{actual output}}_{Y_t}=\underbrace{\textnormal{long-run trend }}_{\bar{Y}_t} + \underbrace{\textnormal{short-run fluctuation }}_{\tilde{Y}_t} \]

Here, \(\bar{Y}_t\) represents the potential output that follows the general trend of GDP, while \(\tilde{Y}_t\) captures short-run fluctuations. The difference between real GDP and potential GDP is known as the output gap.

23.2.1 Okun’s Law

Okun’s law is an empirically observed relationship between unemployment and short-run fluctuations in countries’ production. It is named after Arthur Melvin Okun (1928-1980), who first proposed the relationship in 1962 (see Figure 23.5).

Source: Wikimedia Commons

23.2.2 The reverse multiplier effect

When people experience unemployment, they: - Cut back on their spending on luxuries. - Goods with a relatively high income elasticity of demand are likely to be affected more significantly. - These businesses may reduce orders and lay off workers. - As a result, an increase in unemployment can impact economic activity as a whole, creating further unemployment, with negative effects often varying locally. - Switch their spending to substitute goods, which may be considered inferior goods. This change might lead some firms to experience an increase in demand, such as budget supermarkets.