1 Scope

Recommended reading: Shapiro et al. (2022, ch. 1-3) or Mankiw (2024, pt. I)

Learning objectives:

Students will be able to:

- Define economics and distinguish between microeconomics and macroeconomics.

- Explain the scope and the big questions of economics.

- Differentiate between efficiency and effectiveness, analyzing how both concepts apply to economics and successful management.

- Identify contemporary economic topics, understanding the significant changes that shape the global economy and their relevance to the study of economics.

- Recognize the principles of scarcity and choice, exploring how these concepts underlie economic decision-making.

- Examine the key aspects that define perfect markets, recognizing the limitations of perfect competition in real-world contexts.

- Apply the rational economic way of thinking to recognize that all choices involve trade-offs, benefits, and costs.

- Investigate the role of the price system and Adam Smith’s invisible hand in market operations and resource allocation.

1.1 What is economics?

It is important to note that economics encompasses a wide range of interpretations. There is no single definition that covers all facets. Nevertheless, there are certain aspects on which there is a certain consensus. This is the subject of the next chapter.

1.1.1 Production and productivity

Economics is the study of how to maximize welfare, production, consumption of goods and services, and whatever may be considered beneficial for an economy and the people that live therein.

Wikipedia (2022): “An economy is an area of the production, distribution, and trade, as well as consumption of goods and services. In general, it is defined as a social domain that emphasizes the practices, discourses, and material expressions associated with the production, use, and management of scarce resources. Simplified, one can say that an economy is a system for providing livelihoods to people.”

1.1.2 Efficiency and effectiveness

Economics and successful management revolves around two key concepts: Efficiency and Effectiveness.

Efficiency refers to the ability to achieve an intended result while minimizing waste in terms of time, effort, and resources. It emphasizes performing tasks in the most optimal manner, such as achieving results quickly or at the lowest cost. However, it’s important to note that efficiency can sometimes be applied to the wrong activities, meaning that while the task may be done optimally, the outcome may not be the desired one.

Please keep in mind that efficiency is not an indicator of doing the right things. For example, if you are a business that provides a product that nobody wants to buy anymore, you can produce this product with the highest efficiency possible, but you will ultimately fail.

Effectiveness, on the other hand, is the capacity to produce better results that deliver greater value or achieve more favorable outcomes. It focuses on ensuring that the right tasks are carried out, completing activities successfully, and ultimately reaching one’s goals.

Managers and individuals with goals should choose actions that are effective—meaning those actions allow them to achieve their intended objectives—and they should strive to execute these actions efficiently.

1.1.3 Economic topics

You are studying economics at a time of enormous change. Some of these changes are for the better, while others are for the worse. Studying economics will help you to understand the powerful forces that are shaping and changing our world.

Recent topics in economics:

- COVID

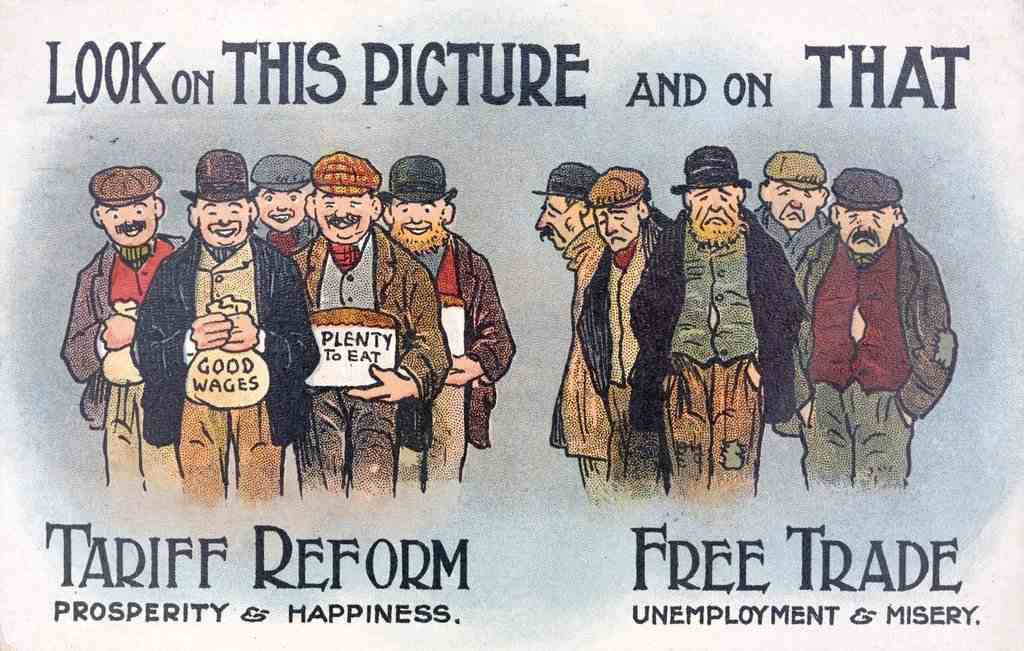

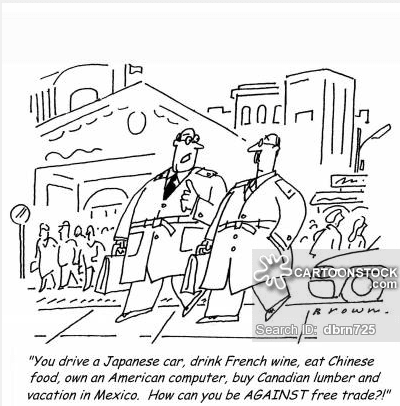

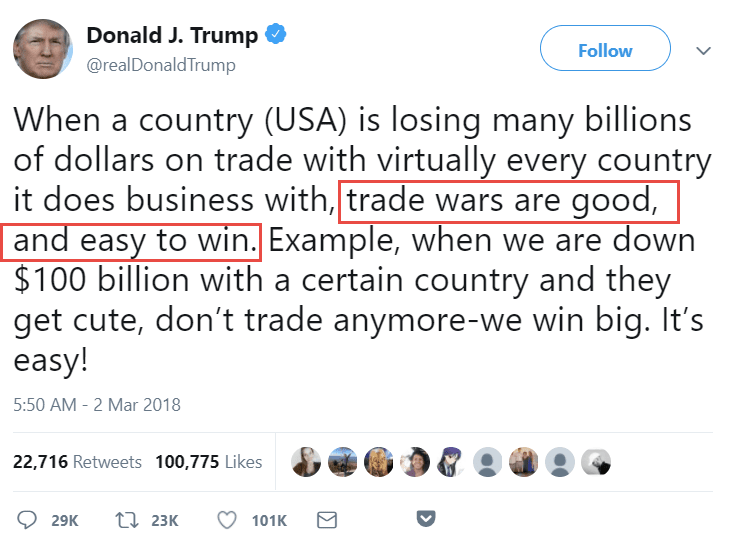

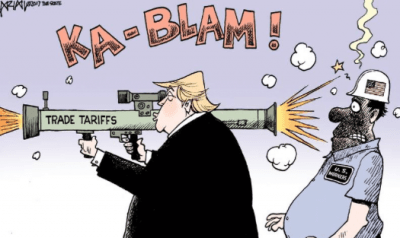

- Protectionism/trade war

- Brexit

- Euro crisis

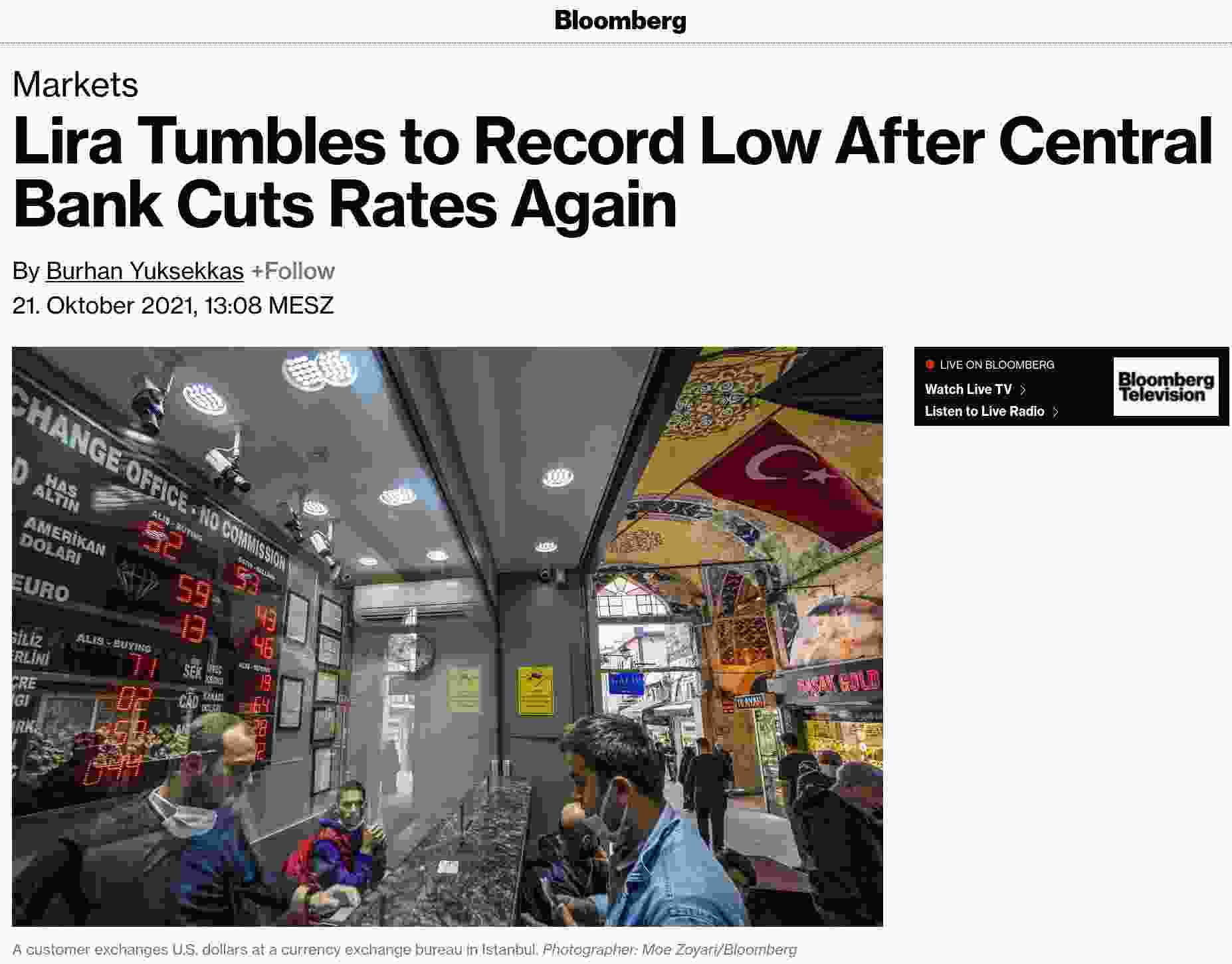

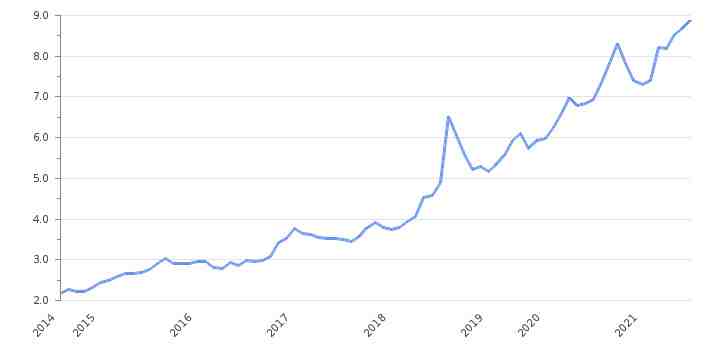

- Monetary policy

- Refugees

- Germany’s trade surplus

- Greece’s debt crisis

- Real estate crisis

- Global financial crisis in 2009

- Economics of the Corona Crisis

- Oil price fluctuations

- U.S. Dollar strength

- Economics of climate change

1.1.4 Definitions

- All economic questions arise because we want more than we can get.

- Our inability to satisfy all our wants is called scarcity.

- Because we face scarcity, we must make choices.

- The choices we make depend on the incentives we face. An incentive is a reward that encourages or a penalty that discourages an action.

Economics is a social science, and like all social sciences, many of the terms used in it are poorly defined. For example, the term economy can be understood differently, as the following quotes from Figure 1.1 to Figure 1.4 demonstrate:

Keynes (1921): The theory of economics does not furnish a body of settled conclusions immediately applicable to policy. It is a method rather than a doctrine, an apparatus of the mind, a technique of thinking, which helps its possessors to draw correct conclusions.

Marshall (2009): “Economics is a study of mankind in the ordinary business of life; it examines that part of individual and social action which is most closely connected with the attainment and with the use of the material requisites of well-being.”

Duesenberry (1960): “Economics is all about how people make choices. Sociology is about why there isn’t any choice to be made.”

Colander (2006): “Economics is the study of how human beings coordinate their wants and desires, given the decision-making mechanisms, social customs, and political realities of society.”

Parkin (2012): “Economics is the social science that studies the choices that individuals, businesses, governments, and entire societies make as they cope with scarcity and the incentives that influence and reconcile those choices.”

Gwartney et al. (2006): “[E]conomics is the study of human behavior, with a particular focus on human decision making.”

Backhouse & Medema (2009): “[E]conomics is apparently the study of the economy, the study of the coordination process, the study of the effects of scarcity, the science of choice, and the study of human behavior.”

Greenlaw & Shapiro (2022): “Economics seeks to solve the problem of scarcity, which is when human wants for goods and services exceed the available supply. A modern economy displays a division of labor, in which people earn income by specializing in what they produce and then use that income to purchase the products they need or want. The division of labor allows individuals and firms to specialize and to produce more for several reasons: a) It allows the agents to focus on areas of advantage due to natural factors and skill levels; b) It encourages the agents to learn and invent; c) It allows agents to take advantage of economies of scale. Division and specialization of labor only work when individuals can purchase what they do not produce in markets. Learning about economics helps you understand the major problems facing the world today, prepares you to be a good citizen, and helps you become a well-rounded thinker.

Backhouse & Medema (2009): “Perhaps the definition of economics is best viewed as a tool for the first day of principles classes but otherwise of little concern to practicing economists.”

Jacob Viner: “Economics is what economists do.” (see Backhouse & Medema, 2009)

Although many textbook definitions are quite similar in many ways, the lack of agreement on a clear-cut definition of economics is not necessarily problematic, as Backhouse & Medema (2009) states:

“[E]conomists are generally guided by pragmatic considerations of what works or by methodological views emanating from various sources, not by formal definitions.”

1.2 Microeconomics vs. Macroeconomics

Parkin (2012): “Microeconomics is the study of the choices that individuals and businesses make, the way these choices interact in markets, and the influence of governments. […] Macroeconomics is the study of the performance of the national economy and the global economy.’’

Microeconomics and macroeconomics are two different perspectives on the economy. The microeconomic perspective focuses on parts of the economy:

- Individuals

- Firms

- Industries

Some examples of microeconomic questions are:

- Why are people downloading more movies?

- How would a tax on e-commerce affect eBay?

The term macro comes from the Greek word makros, meaning large. Thus, it studies groups or the entire economy using aggregate measures related to welfare and standards of living such as:

- National income

- Money

- Total (un)employment

- Aggregate demand and supply

- Total savings

- Inflation

- General price level

- International trade

- Balance of trade,

- …

Macroeconomics employs two key policy approaches to pursue these objectives:

- Fiscal policy pertains to the regulation of government revenue, expenditures, and debt to generate positive impacts while averting negative effects on income, output, and employment.

- Monetary policy involves controlling money supply and credit to stimulate business activities, foster economic growth, stabilize price levels, attain full employment, and achieve balance of payments equilibrium.

Some examples of macroeconomic questions are:

- Why is the U.S. unemployment rate so high?

- Can the Federal Reserve make our economy expand by cutting interest rates?

Why separate micro and macroeconomics? Certainly, events occurring at the micro-level can provide insights into phenomena observed at the macro-level, and vice versa. Thus, there is an interdependence of these disciplines. Nevertheless, there remains value in distinguishing them because:

- What is good at the micro level doesn’t have to be good for the economy as a whole.

- Macroeconomic problems can only be comprehended and solved through macro-level policy actions and programs.

1.3 The scope of economics in five questions

- How do choices end up determining what, where, how, and for whom goods and services get produced?

- When do choices made in the pursuit of self-interest also promote the social interest?

1.3.1 What?

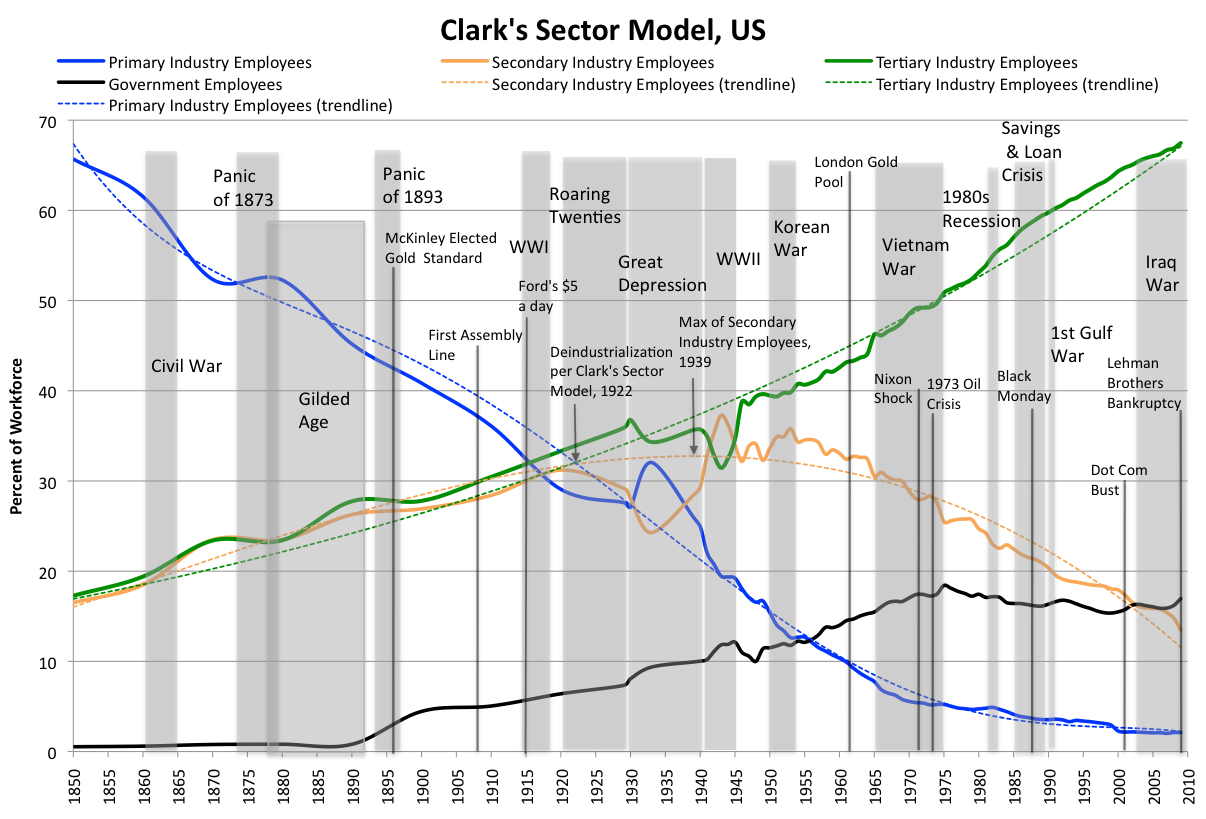

As demonstrated in Figure 1.5, what we produce changes over time.

Source: www.63alfred.com

1.3.2 How?

Goods and services are produced by using productive resources that economists call factors of production:

- Land (aka natural resources): These are the gifts of nature that we use to produce goods and services.

- Labor: This is the work time and effort that people devote to production. The quality of labor depends on human capital, which encompasses the knowledge and skill that people obtain from education, on-the-job training, and work experience.

- Capital: Refers to the tools, instruments, machines, buildings, and other constructions employed in the production process.

- Entrepreneurship: This is the human resource that organizes labor, land, and capital. Entrepreneurs come up with new ideas about what and how to produce, make business decisions, and bear the risks that arise from these decisions.

What determines the quantities of factors of production used to produce goods and services is a typical economic question.

1.3.3 For whom?

Who gets the goods and services depends on the incomes that people earn. People earn their incomes by selling the services of the factors of production they own:

- Land earns rent.

- Labor earns wages.

- Capital earns interest.

- Entrepreneurship earns profit.

Why is the distribution of income so unequal? Why do women and minorities earn less than white males?

1.3.4 Where?

We all know the World is not flat: The placement of land, labor, capital, and entrepreneurs in space is important. In particular, Regional Science considers that importance.

“No other discipline can claim such a wide scope of interest and relevance to today’s rapidly changing World. Thus, contrary to the claims of the ‘end of geography’, the process of globalization is making geography more important than ever.” Sokol (2011)

Unfortunately, the main microeconomic and macroeconomic textbooks usually refrain from discussing the question “Where?”. One reason for this could be that the introduction of space into the theory is not trivial. Ignoring the existence of regional differences and transport is accompanied by a lack of reality and may lead to wrong conclusions.

1.5 The economic way of thinking

The questions that economics attempts to answer tell us something about the scope of economics, but they do not tell us (1) how economists think and (2) how economists conduct research to find answers.

1.5.1 A choice is a tradeoff

Before discussing how economists do research, let’s look at six key concepts that define the economic way of thinking:

- A choice is a tradeoff.

- People make rational decisions by comparing benefits and costs.

- Benefit is what you get out of something.

- Cost is what you have to give up to get something.

- Most choices are how-much choices made at the margin.

- Choices respond to incentives.

Due to scarcity, we are forced to make a choice. Whenever we make a decision, we choose from the available alternatives. It can be helpful to think of each choice as a trade-off - an exchange in which we give up one thing to get another.

The questions of what, how and for whom become clearer when we consider trade-offs:

- What? Trade-offs occur when individuals decide how to divide their income, when governments decide how to spend tax revenues, and when companies decide what products to make.

- How? Trade-offs occur when companies evaluate different production technologies to maximise efficiency.

- For whom? Trade-offs affect the distribution of purchasing power among citizens. Government redistribution of income from the wealthy to the less fortunate is an example of the great trade-off - the balance between equality and efficiency.

The production of goods and services—what is produced, how it is produced, and for whom it is produced—changes over time, leading to improvements in the quality of our economic lives, provided we make wise decisions. The quality of those decisions hinges on the tradeoffs we face.

1.5.2 Rational choices

Economists view the choices that people make as rational. A rational choice is one that compares costs and benefits and achieves the greatest benefit over cost for the person making the choice.

1.5.3 Benefit: What you gain

The utility of an item refers to the gain or pleasure it provides and is determined by preferences, that is, what a person likes or dislikes and the intensity of those feelings. Economists measure utility as the maximum amount a person is willing to give up to obtain something.

1.5.4 Cost: What you must give up

When considering a choice as a tradeoff, it is essential to emphasize cost as an opportunity foregone. The opportunity cost of something is the highest-valued alternative that must be sacrificed to get it.

1.5.5 Choosing at the margin

Choosing between studying or watching Netflix is rarely an all-or-nothing decision. Instead, you consider how many minutes to allocate to each activity. In making this decision, you compare the benefit of a bit more study time against its cost, effectively making your choice at the margin.

People often make choices at the margin, which means they evaluate the consequences of making incremental changes in the use of their resources.

The benefit derived from pursuing a small increase in activity is known as its marginal benefit, while the opportunity cost of that incremental increase is referred to as its marginal cost.

Our choices respond to incentives. For any activity, if the marginal benefit exceeds the marginal cost, people have an incentive to increase that activity. Conversely, if the marginal cost exceeds the marginal benefit, people have an incentive to reduce that activity.

1.6 International economics

International economics is covered in more detail in Chapter 29 to Chapter 37. However, let us briefly discuss the scope of this important area of economics.

1.6.1 What is international trade?

International trade is the exchange of capital, goods, and services across international borders or territories. Questions of international trade include:

- Why do nations trade?

- What do they trade?

- What is the effect of trade policies on trade and welfare?

- Can trade in goods substitute for factor mobility?

- Is free trade better than autarky?

- What are the effects of trade on income distribution?

- If there are winners and losers from trade liberalization, can the former compensate the latter?

- If nations gain from trade, how are the gains distributed?

- What are the welfare effects of various trade policies?

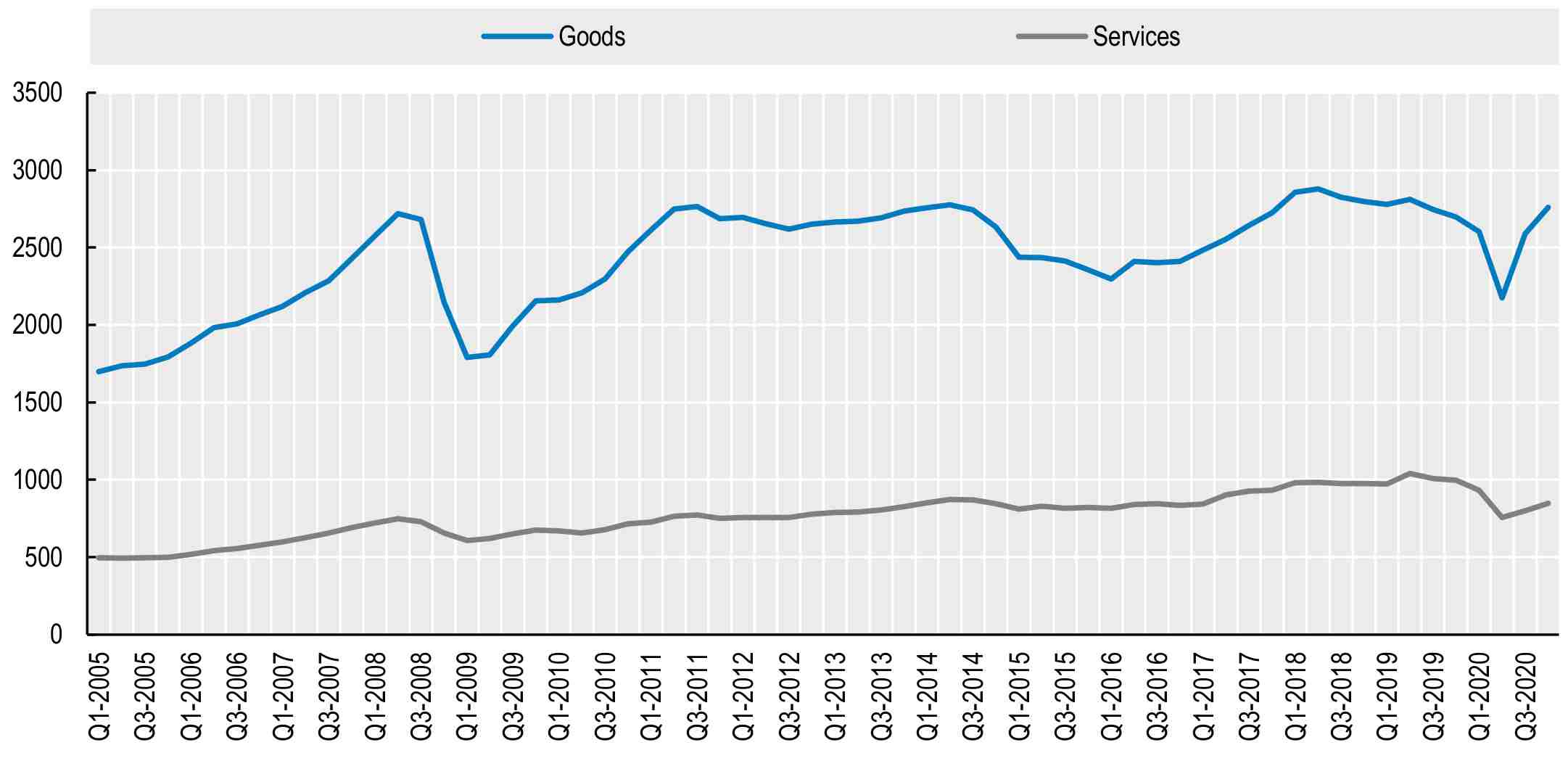

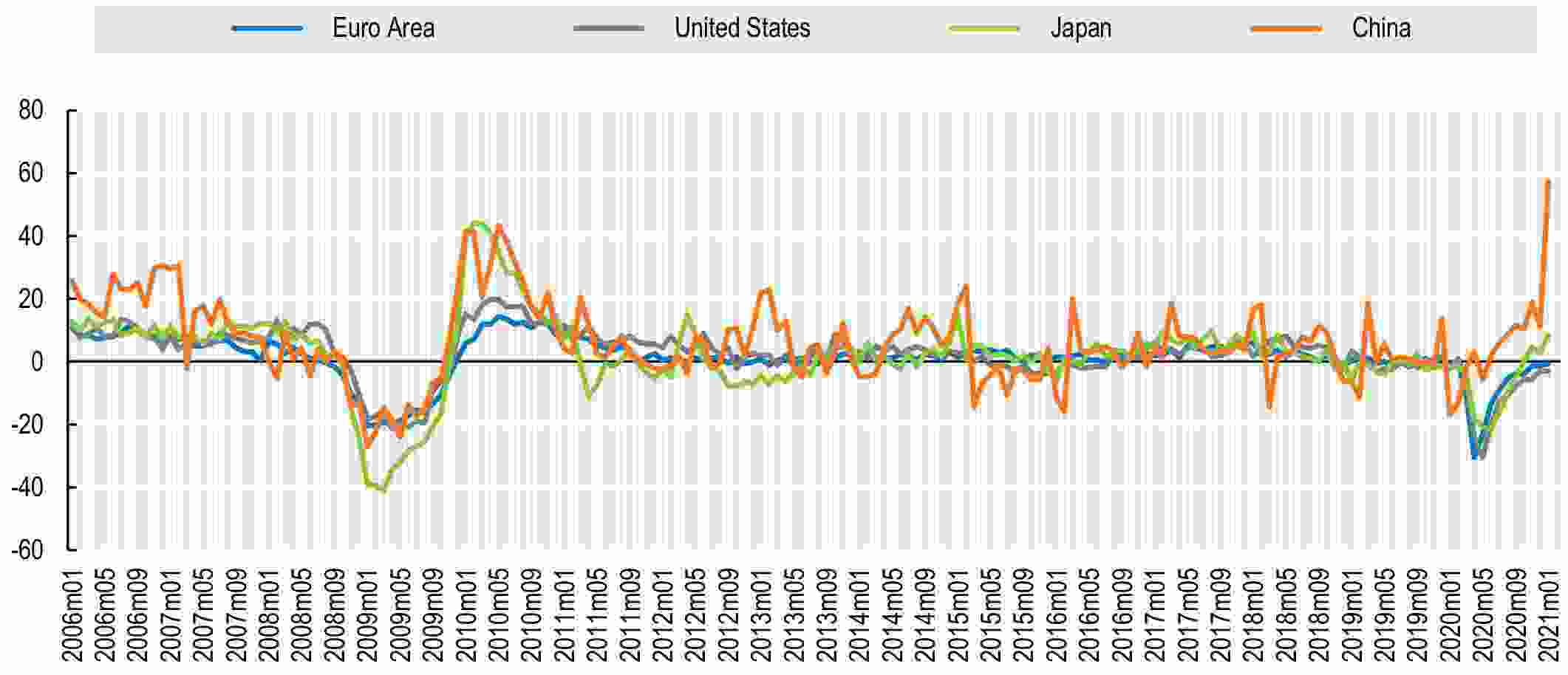

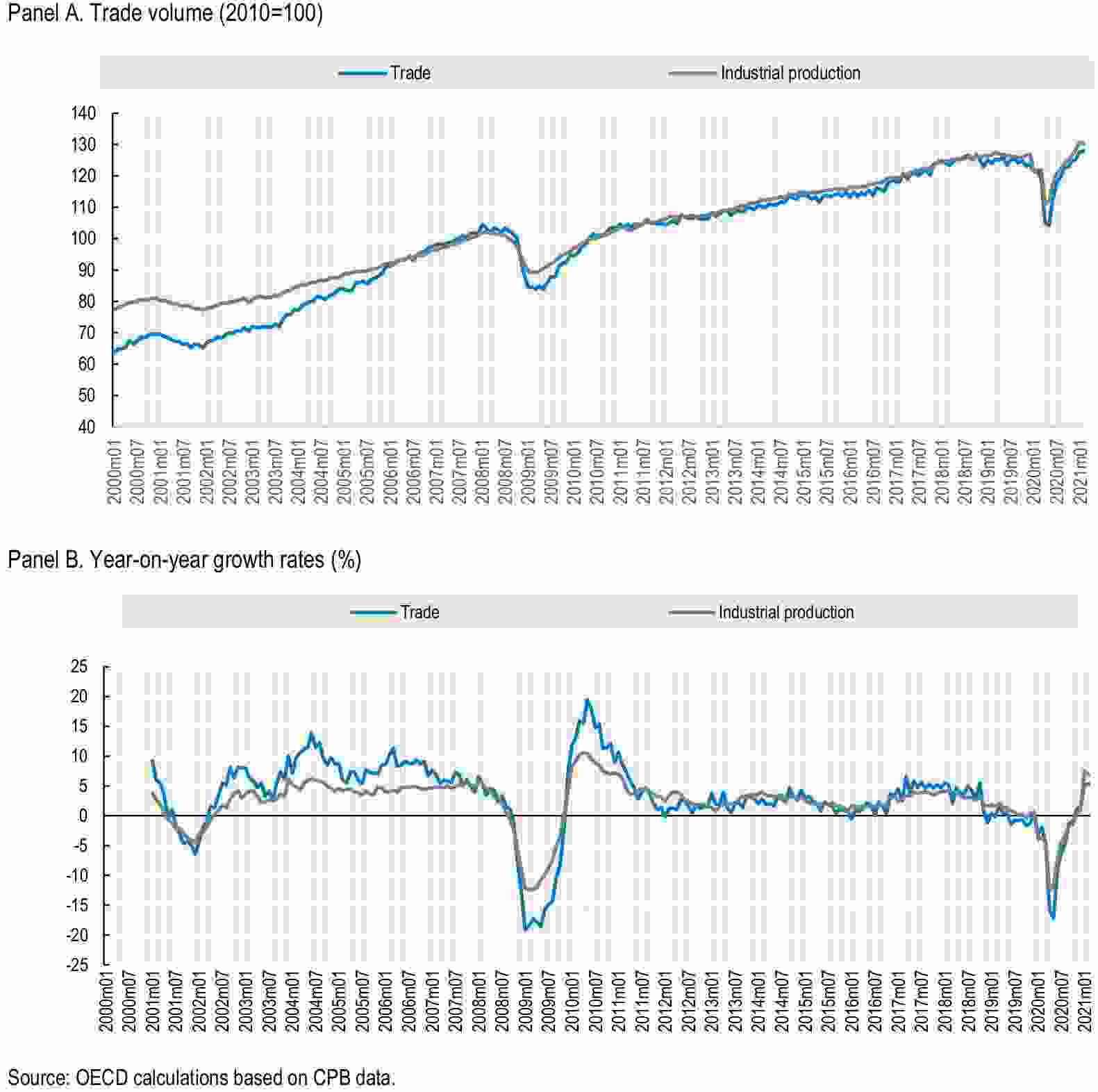

1.6.2 COVID and international economics: Stylized facts

See Figure 1.8 to Figure 1.10 and read Arriola et al. (2021) for further information.

Source: Arriola et al. (2021)

Source: Arriola et al. (2021)

Source: Arriola et al. (2021)

1.6.3 What is international monetary economics?

International monetary economics focuses on the financial aspects of international trade. It studies the flows of money across countries and their effects on economies as a whole.

1.7 What is international trade policy?

International trade policy encompasses the interplay of national interests affecting trade across borders. It is based on the assumption that a country’s international trade policy serves its citizens’ and companies’ interests.