32 Basics

Recommended readings: Suranovic (2012, Chapters 2, 3, 5)

Learning objectives:

Students will be able to:

- Understand the basic concepts underpinning international trade, including the principle of mutual benefits.

- Evaluate reasons for trade, including technology differences, resource endowments, and government policies.

- Explain the difference of absolute comparative advantage and their role in driving trade patterns.

- Understand how differences in labor and capital endowments influence trade patterns.

- Discuss the impact of international trade on factor prices.

Trade is usually a voluntary decision by buyers and sellers, which means that transactions would not take place if one party were to lose from the exchange. While this reasoning is persuasive, it alone does not fully justify unrestricted international trade. In the following chapters, we will look at the concept that trade should be mutually beneficial to the parties directly involved. We will also discuss the ways in which trade can be beneficial to all parties, even though it is not necessarily beneficial to all. The remainder is structured as follows:

- Section 32.1 explains Mankiw’s principle that trade can make everyone better off.

- Section 32.2 paraphrases the sources of international trade.

- Section 32.3 provides a theoretical framework of trade and shows that under certain circumstances international trade can yield a miserable growth path for a country.

- Section 32.4 explains that more trade does not have to be good for a country’s wealth.

- Chapter 33 introduces the concept of comparative advantage. It claims that trade is due to autarky price differences that stem from country-specific differences such as technology, factor endowments, or taste.

- Chapter 34 shows that opening up to free trade generates winners and losers and that countries’ endowments with labor and capital determine patterns of trade.

32.1 Trade can make everyone better off

Source: Harvard.edu and Mankiw (2024).

N. Gregory Mankiw (*1958) is one of the most influential economists. In his best-selling textbook Principles of Economics (Mankiw, 2024, pp. 8–9) he claims ten principles of economics of which one is entitled Trade can make everyone better off which he explains as follows:

You have probably heard on the news that the Japanese are our competitors in the world economy. In some ways, this is true, for American and Japanese firms do produce many of the same goods. Ford and Toyota compete for the same customers in the market for automobiles. Compaq and Toshiba compete for the same customers in the market for personal computers.

Yet it is easy to be misled when thinking about competition among countries. Trade between the United States and Japan is not like a sports contest, where one side wins and the other side loses. In fact, the opposite is true: Trade between two countries can make each country better off.

To see why, consider how trade affects your family. When a member of your family looks for a job, he or she competes against members of other families who are looking for jobs. Families also compete against one another when they go shopping, because each family wants to buy the best goods at the lowest prices. So, in a sense, each family in the economy is competing with all other families.

Despite this competition, your family would not be better off isolating itself from all other families. If it did, your family would need to grow its own food, make its own clothes, and build its own home. Clearly, your family gains much from its ability to trade with others. Trade allows each person to specialize in the activities he or she does best, whether it is farming, sewing, or home building. By trading with others, people can buy a greater variety of goods and services at lower cost.

Countries as well as families benefit from the ability to trade with one another. Trade allows countries to specialize in what they do best and to enjoy a greater variety of goods and services. The Japanese, as well as the French and the Egyptians and the Brazilians, are as much our partners in the world economy as they are our competitors.

32.2 Reasons for Trade

Trade involves willingly giving up something to receive something else in return, which should benefit both parties involved, although not necessarily everyone affected by the trade. We will discuss the negative effects of international trade on bystanders later. In this section, we briefly outline basic reasons for individuals and hence countries to engage in trade. Of course, the list is incomplete.

Differences in Technology: Advantageous trade can occur between countries if they have different technological abilities to produce goods and services. Technology refers to the techniques used to convert resources (labor, capital, land) into outputs. Differences in technology form the basis for trade in the Ricardian Model of comparative advantage. We will revisit this in more detail in Chapter 33.

Differences in Endowments: Trade also occurs because countries differ in their resource endowments, which include the skills and abilities of the workforce, available natural resources, and the sophistication of capital stock such as machinery, infrastructure, and communication systems. Differences in resource endowments are the basis for trade in the pure exchange models (see Section 32.3) and the Heckscher-Ohlin Model (see Chapter 34).

Differences in Demand: Trade between countries occurs because demands or preferences differ. Individuals in different countries may prefer different products even if prices are the same. For example, Asian populations might demand more rice, Czech and German people more beer, the Dutch more wooden shoes, and the Japanese more fish compared to Americans.

Economies of Scale in Production: Economies of scale, where production costs fall as production volume increases, can make trade between two countries advantageous. This concept, known as increasing returns to scale, plays a significant role in Paul Krugman’s New Trade Theory, which we will discuss later.

Existence of Government Policies: Government tax and subsidy programs can create production advantages for certain products, leading to advantageous trade arising solely from differences in government policies across countries. We will explore the impact of tariffs and regulations in Chapter 37.

32.3 Exchange economy

32.3.1 A simple barter model

The simplest example to show that trade can be beneficial to people is the barter model. In trade, barter is a system of exchange in which participants in a transaction directly exchange goods or services for other goods or services without using a medium of exchange, such as money.

Source: Wikipedia

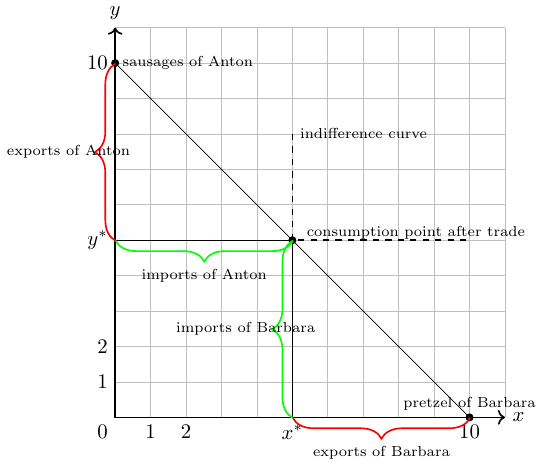

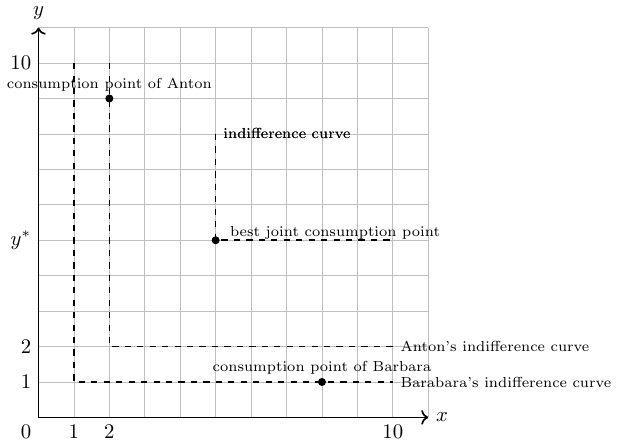

Suppose there are two people, Anton (A) and Barbara (B). Anton has 10 Weißwürste (white sausages) and Barbara has 10 pretzels. Together, they are isolated from the rest of the world for a few days due to a natural disaster. Fortunately, they both have additional access to an endless supply of sweet mustard and beer and they now wonder how to share pretzels and sausages the upcoming days. Let’s assume that both of them accept only a white sausage eaten together with a pretzel. That is, eating two pretzels with a sausage is no better than eating a pretzel and a sausage. After some discussion, Barbara gives 5 pretzels and Anton gives Barbara 5 sausages in return. They strongly believe that there is no better way to share food.

This example shows that trade can be beneficial for two individuals. Here we basically assume two things. Firstly, two individuals can trade and secondly, they are endowed with different goods.

32.3.2 Terms of trade

The terms of trade is defined as the quantity of one good that exchanges for a quantity of another. It is typical to express the terms of trade as a ratio.

In the example of Barbara and Anton, the exchange of goods occurs at a 1:1 ratio. In economics, this is referred to as the terms of trade being 1. The terms of trade are defined as the relative price of exports in relation to imports, or in other words, how much of one good can be exchanged for another. For instance, determining how many sausages can be exchanged for how many pretzels. The terms of trade, determined by the two trading partners, depend on a variety of distinct factors, including:

Preferences: For trade to occur, each trader must desire something the other has and be willing to give up something of their own to obtain it. Formally, the expected utility of consuming some of Anton’s bread must exceed the disutility of foregoing a few of his sausages, and vice versa for Barbara. Typically, the goods are substitutable rather than perfectly complementary, as is assumed in our specific example.

Uncertainty: Both individuals have clear preferences. If Barbara has never tried Anton’s sausages, and Anton typically prefers bread over pretzels, offering free samples before an exchange could reduce uncertainty. Without a sample, their trade would be based on expectations about the taste of the other’s product.

Scarcity: The availability of the two goods influences the terms of trade. If, for instance, Barbara has 1000 pretzels, the terms of trade with the sausages would likely change.

Size: The physical size of the goods can impact the terms of trade.

Quality: The quality of goods affects the terms of trade. If the pretzels are stale and hard, both might prefer fewer pretzels per sausage.

Persuasion: If Barbara is a more persuasive salesperson than Anton, she might be able to negotiate more favorable terms of trade.

Government Policy: Taxes imposed by an official based on the traded quantities could affect the terms of trade. Additionally, if laws prevent Barbara and Anton from meeting, no trade would occur.

32.3.3 Endowments in an Exchange Economy

In this section, we examine a basic scenario where productive units within an economy are unable to adjust their output to recent changes in world market prices, which stem from global demand and supply fluctuations. Economists refer to the resulting availability of goods as endowments. Essentially, a country is endowed with a certain quantity of goods and seeks to trade these goods on global markets to maximize its welfare. In Chapter 34 we will assume that countries are endowed with a certain amount of factors of production that they can use to produce various goods.

32.3.3.1 Fixed production

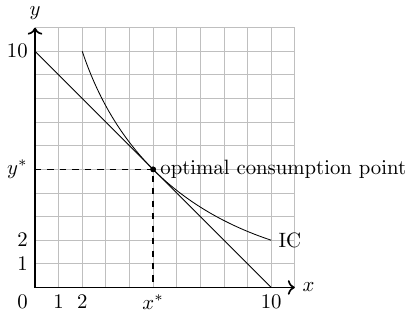

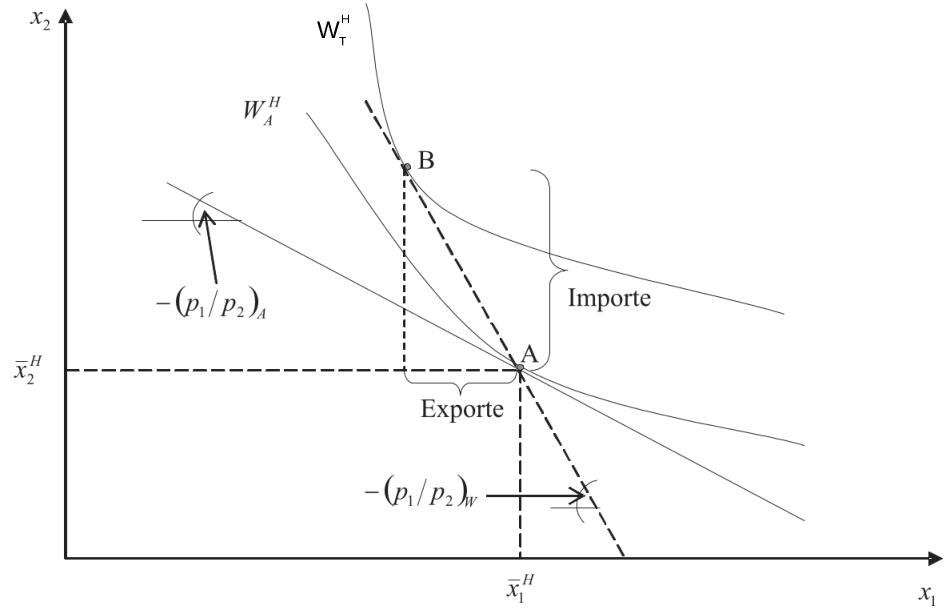

Imagine that country H produces \(\bar{x}^H_1\) units of good 1 and \(\bar{x}^H_2\) units of good 2. In autarky (a state of where there is no trade), it consumes all the goods it produces. This scenario is shown in Figure 32.7, where point A represents the optimal welfare outcome with utility \(W^H_A\) for country H in autarky.

Now, let’s assume country H can trade with the rest of the world at global market prices, where the price ratio of good 1 to good 2 in the world market, \(( \frac{p_1}{p_2} )_W\), is greater than in autarky, \(( \frac{p_1}{p_2} )_A\): \[\begin{align} \left( \frac{p_1}{p_2} \right)_W > \left( \frac{p_1}{p_2}\right)_A, \end{align}\]

With trade, country H can achieve a higher utility, \(W_T^H>W_A^H\), by exporting good \(x_1\) and importing good \(x_2\), thus moving to a more advantageous consumption point.

32.3.3.2 Flexible production

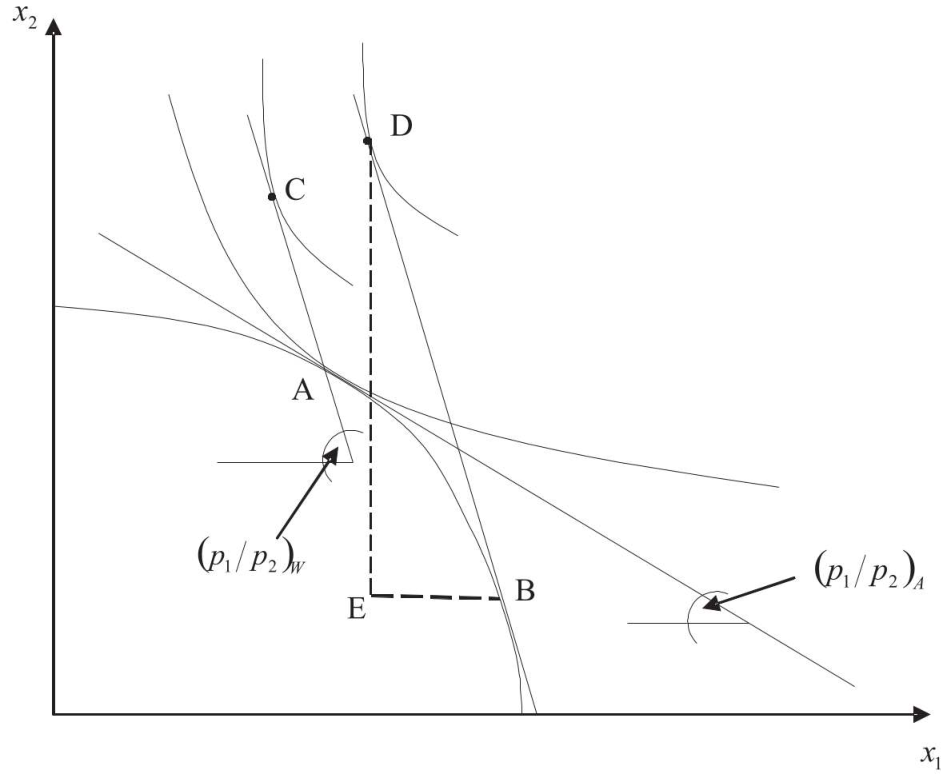

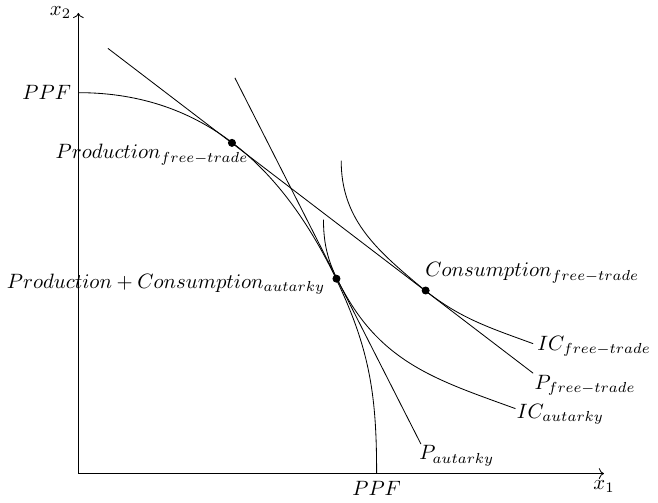

- Trade is even more beneficial to a country if it can adjust its production to export more goods that are relatively high priced in the world market. This statement is shown in Figure 32.8.

- In autarky, optimal consumption would be at point A and optimal consumption would be at point C under free trade. Now suppose that producers in country H know that they can sell their goods at price \(p_1^W\) and \(p_2^W\) before deciding what to produce. Then they would choose production point B on the production frontier curve to export good \(x_1\) and import good \(x_2\) at price \((\frac{p_1}{p_2})_A\) to be consumed at point D. Welfare at point D is higher than at point C or A because we end up at the highest indifference curve.

32.4 More trade is not necessarily good (immiserizing growth)

So far, I have implicitly assumed that the world market price is fixed and not changed by the entry of country H into the free trade market. When the latter is the case, economists speak of a small open economy (SOE). In general, a SOE is an economy that is so small that its policies do not change world prices.

Suppose that country H is not an SOE. What would happen to world prices if country H offered a lot of good \(x_1\) to receive good \(x_2\)? Obviously, \((\frac{p_1}{p_2})_W\) would fall. In the worst case, country H is so large that \[\left(\frac{p_1}{p_2}\right)_W=\left(\frac{p_1}{p_2}\right)_A.\] This means that country H has no benefits from free trade.

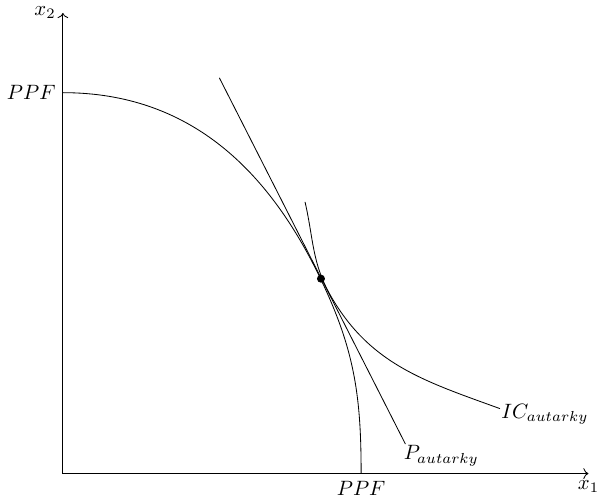

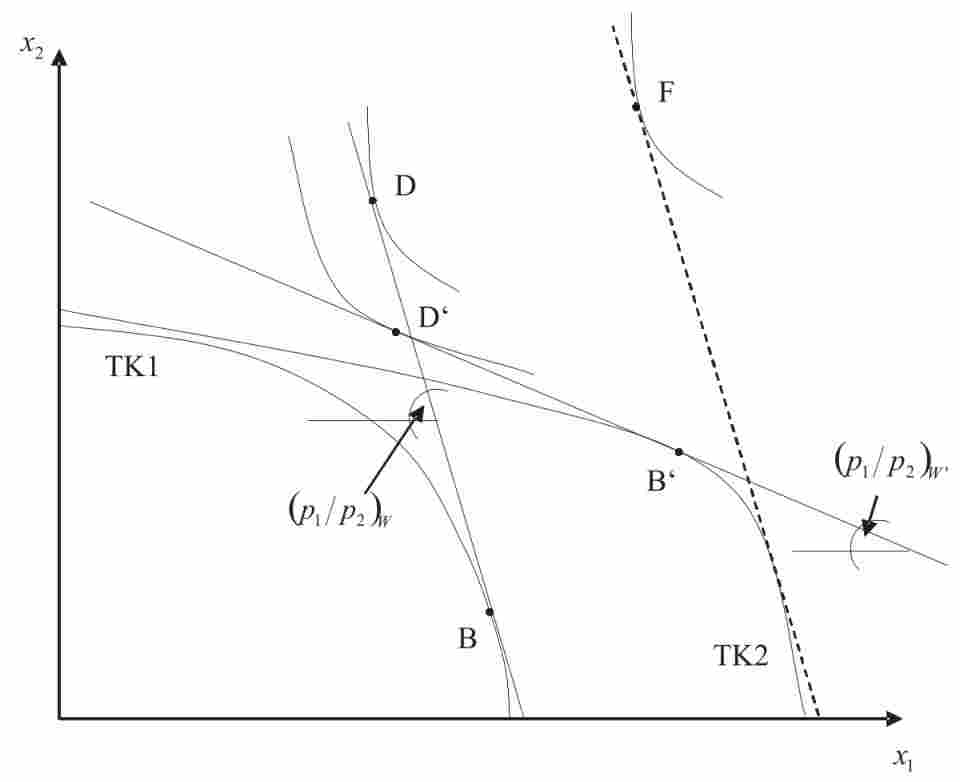

Assuming that a (large) country cannot opt out from free trade and that the exporting sector grows, there is a theoretical scenario called immiserizing growth that shows that free trade countries are worse off in the long run. This scenario is illustrated in Figure 32.11. The figure summarizes two periods. In the first period, country H produces at point B and consumes at point D, trading goods at world prices \((\frac{p_1}{p_2})_W\). Then country H grows in sector 1. This is shown in the new production possibility curve TK2. If country H were able to trade at the old world price, it would be able to consume at point F. Unfortunately, country H is not a SOE, and therefore world prices (from country H’s perspective) deteriorate to \((\frac{p_1}{p_2})_W^{'}\). This has bad implications for country H, since its optimal consumption is now at point D’, which has lower welfare relative to point D. However, this is not an argument against trade, since the welfare at point D’ is still above the production possibility curve in autarky, TK1.