34 Endowments

34.1 Nobel prize winning theory

The theory which we discuss in this section explains trade because of different endowments. It is also known as the Heckscher-Ohlin model. It is named after two Swedish economist, Eli Heckscher (1879-1952) and Bertil Ohlin (1899-1979). Bertil Ohlin received the Nobel Prize in 1977 (together with James Meade). The HO-Model, as it is often abbreviated, was the main reason for the price. Here is an excerpt of the Award ceremony speech:

The Ricardo model explains international trade as advantageous because of comparative advantages that are the result of technological differences. This means that comparative advantage in the Ricardian model is solely the result of productivity differences. The size of a country or the size of the countries’ endowments does not matter for comparative advantage in the Ricardian model because there is only one factor of production in Ricardian models, namely labor. However, the assumption that there is only one factor of production is unrealistic, and we should ask what happens if there is more than one factor of production but no productivity differences? What happens if the two factors are available differently in different countries? What is the significance of endowment differences for international trade? And which owner of a factor of production will be a winner when a country opens up to world trade, and who will lose? The HO model can provide answers to these questions.

In Table 34.1, I show that countries do indeed differ substantially in their total factor productivity, capital stock, and labor endowments, which are likely correlated with total population.

| RegionCode | Capital stock at current PPPs (in mil. 2011USD) | Population (in millions) | Capital stock per capita |

|---|---|---|---|

| ITA | 10421041 | 60 | 174885 |

| ESP | 7806612 | 47 | 167518 |

| FRA | 10405968 | 65 | 160395 |

| GBR | 9973122 | 63 | 159019 |

| DEU | 12687682 | 80 | 157738 |

| USA | 48876336 | 310 | 157729 |

| AUS | 3332890 | 22 | 150382 |

| CAN | 5065392 | 34 | 148431 |

| JPN | 17161376 | 127 | 134790 |

| SAU | 3716382 | 28 | 132300 |

| KOR | 6052155 | 49 | 123287 |

| TWN | 2835890 | 23 | 122549 |

| ROU | 1271652 | 20 | 62647 |

| VEN | 1765996 | 29 | 60905 |

| BRA | 9869311 | 199 | 49691 |

| RUS | 6746460 | 143 | 47126 |

| POL | 1769004 | 39 | 45859 |

| THA | 2977965 | 67 | 44652 |

| IRN | 3234132 | 74 | 43555 |

| ARG | 1773984 | 41 | 43034 |

| MEX | 5054693 | 119 | 42613 |

| TUR | 2938288 | 72 | 40634 |

| UKR | 1616826 | 46 | 35420 |

| IDN | 8146254 | 242 | 33716 |

| COL | 1446480 | 46 | 31501 |

| CHN | 42218080 | 1341 | 31483 |

| PER | 681036 | 29 | 23185 |

| PHL | 1560017 | 93 | 16767 |

| IRQ | 443733 | 31 | 14375 |

| IND | 15356803 | 1231 | 12475 |

Source: Penn World Tables 9.0

34.2 The Heckscher-Ohlin (factor proportions) model

Assumptions:

Two countries: Home country and foreign country. Variables referring to foreign countries are marked with an asterisk, \(*\).

Two goods: \(x\) and \(y\).

Two factors of production: \(K\) and \(L\). This is new in relation to the Ricarkian model! Let’s name the factors \(K\) and \(L\), which stands for capital and labor.

Goods differ in terms of their need for factors of production: \[\frac{K_y}{L_y} \neq \frac{K_x}{L_x}.\] This means that one good must be produced in a capital-intensive way and the other in a labor-intensive way. If we assume that good \(y\) is capital intensive and good \(x\) is labor intensive in production, we can write: \[\begin{align*} \frac{K_y}{L_y} > \frac{K_x}{L_x}. \end{align*}\] In this inequality, the quantity of capital required to produce good \(y\), \(K_y\), is on the left-hand side relative to the quantity of labor required to produce good \(y\), \(L_y\), that is, the capital intensity of good \(y\).The capital intensity of good \(x\) is on the right-hand side of the inequality. Rewriting this inequality, we can express it in terms of labor intensities: \(\frac{L_y}{K_y} < \frac{L_x}{K_x}.\) It should be clear that both inequalities say the same thing.

No technology differences between countries: Since we already know from Ricardian theory that productivity or technology differences are a source of international trade, we do not want to explain the same thing again with the HO model. So we assume that all input coefficients are the same in all countries.

Different relative factor endowments: \[\frac{K}{L} \neq \frac{K^*}{L^*}.\] Since countries are assumed to have different factor endowments, the model links a country’s trade pattern to its endowment of factors of production. The capital-labor ratio in the home country, \(\frac{K}{L}\), must differ from the ratio abroad. Suppose the home country is capital-rich and the foreign country is labor-rich. Then we have the following ratios between capital and labor in the two countries: \[\begin{align*} \frac{K}{L} > \frac{K^*}{L^*}. \end{align*}\] This means that the capital-labor ratio (a country’s capital intensity) is higher in the home country than abroad. In terms of the ratio between labor and capital, that is, the labor intensity of a country, this can be expressed as follows: \(\frac{L}{K} < \frac{L^*}{K^*}.\) It should be clear that both inequalities say the same thing.

Free factor movement between sectors Both factors can be used in the production of both goods. Note that cross-country movement of factors (migration, foreign direct investment) is not allowed.

No trade costs Final products can be traded without any costs.

Equal tastes in countries and homothetic preferences Consumers in both countries have the same utility function. Homothetic preferences simply mean that for given relative prices, income does not affect the ratio of consumption.

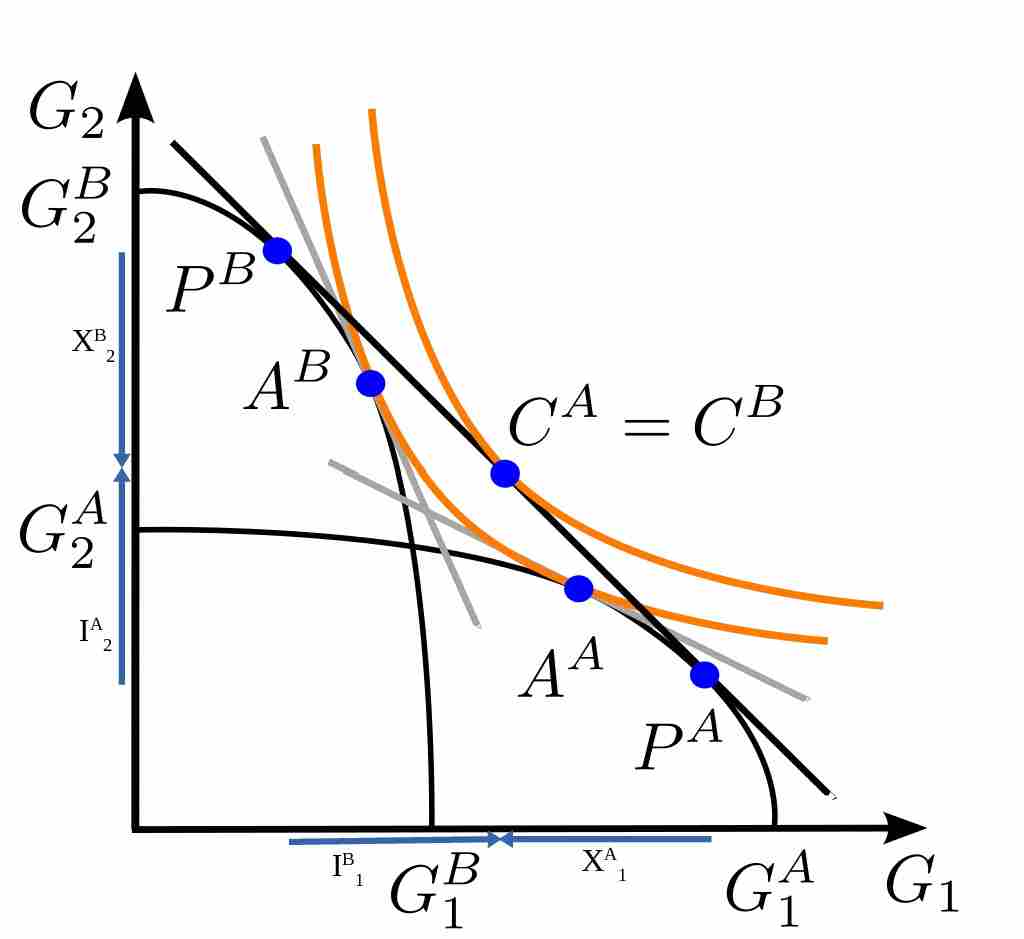

34.3 Heckscher-Ohlin theorem

- Consider that the home country has relatively more capital and the foreign country relatively more labor and that the good \(y\) is capital intensive in production whereas the good \(x\) is labor intensive.

- Then it is relatively cheap for the home country to produce the capital-intensive good because it is endowed with a lot of capital, while it is relatively costly to produce the good with which the country is hardly endowed.

- Thus, the home country has a comparative advantage in producing the capital-intensive good.

- The opposite is true for the foreign country.

34.4 Factor-price equalization theorem

- As a result of the Heckscher-Ohlin theorem, output of the good in which the country has a comparative advantage would increase. The capital intensive country will produce more capital intensive goods and the labor intensive country will produce more labor intensive goods.

- As the production of the good that makes intensive use of the abundant resource increases, the demand for that resource will also increase. Demand for the scarce resource will also increase, but to a lesser extent.

- If production of the good that intensively uses the scarce resource decreases, both abundant and scarce resources will be released, but relatively more of the scarce resource than of the abundant resource.

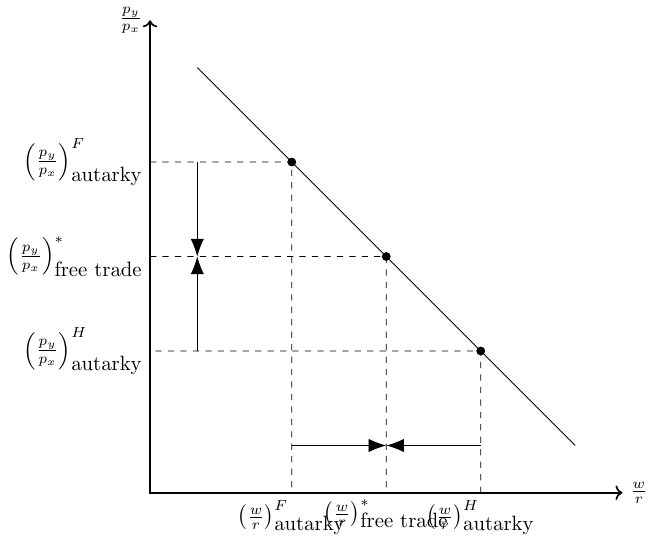

- In autarky, the relatively scarce factor in the home country was labor and factor prices were as follows: \[ \frac{w}{r}>\frac{w^*}{r^*} \]

- After opening to trade, production shifts to the home country so that the wage falls (\(w\downarrow\)) and the rent rises (\(r\uparrow\)).

- After opening to trade, production shifts abroad so that the wage rises, \(w^*\uparrow\), and the rent falls, \(r^*\downarrow\).

- This reallocation process, and hence the change in factor prices, continues until factor prices are equal in all countries: \[

\frac{w}{r}=\frac{w^*}{r^*}

\]

- Figure 34.1 visualizes the reasoning behind the factor-price equalization theorem.

- I recommend a clip of Mike Moore explaining how trade based on factor endowments affects wages and returns to capital, see this video:

Why does the Factor-Price Equalization Theorem not (fully) hold?

In the real world, factor prices do not equalize due to frictions such as transportation costs, trade barriers, and the presence of goods that are rarely or never traded.

Trade as an alternative to factor movements:

The factor price equalization theorem contains an interesting insight: if a country allows free trade in its products, it will automatically export the abundant factor indirectly in the form of goods that intensively use the abundant factor.