28 Negative interest rates policy

28.1 Do negative interest rates work?

Learning objectives:

Students will be able to:

- Explain and evaluate the goals and the effectiveness of a monetary policy with negative interest rates policy (NIRP).

- What is the objective of ECB’s NIRP?

- How can ECB’s NIRP affect economies?

- What is special about a NIRP from a macroeconomic perspective?

- Can negative central bank policy rates translate into negative deposit rates or negative lending interest rates (the cost of debt for the borrower)?

- Determine whether lowering interest rates below zero can be an effective tool for stimulating aggregate demand.

- Identify the downsides of a NIRP.

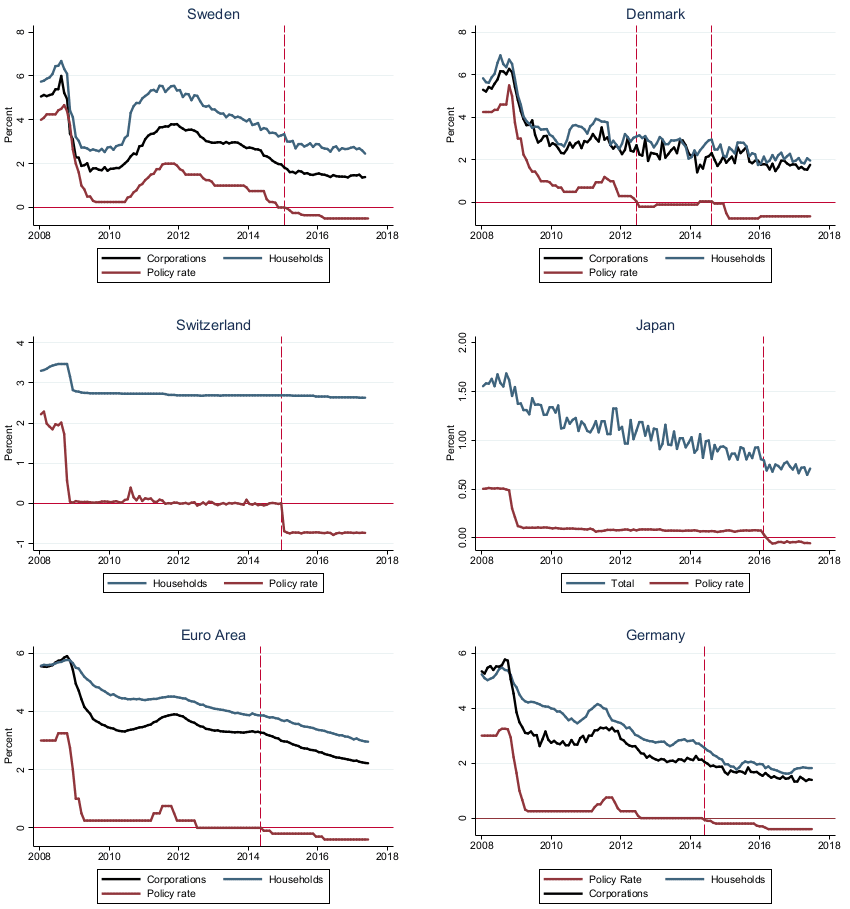

Abstract: In recent years, the European Central Bank (ECB) and some other central banks engaged in a radical new policy experiment by setting negative policy rates. This course discusses whether negative interest rates policy (NIRP) is an effective tool for stimulating aggregate demand and keeping prices at a stable inflation rate of 2%. In particular, I present aggregate and bank-level data demonstrating that once the policy rate turns negative, the pass-through to deposit and lending rates seems to be limited, see Figure 28.1.

Source: Source: app.hedgeye.com

28.2 My stamps taught me a lot

I was about 10 years old and passionate about collecting stamps when I discovered an interesting stamp in an album I had received as a gift. Curious, I asked my father if I was now a double millionaire, see Figure 28.2. Unfortunately, he had to disappoint me.

Lesson 1: Currencies can disappear and their value over time is not fixed.

Starting in 2002, Deutsche Post refused to accept all my mint stamps denominated in pfennigs. The ECB stamp is denominated in pennies and cannot now be used.

Lesson 2: Currency reforms can occur without war or hyperinflation, and assets can be lost with them.

Even if the ECB stamp were still accepted, its current value in pennies would not be enough to mail a letter. Today, it costs 156 pfennigs, or 80 cents, to send a letter. That means sending a letter has become 40% more expensive.

Lesson 3: Inflation still exists.

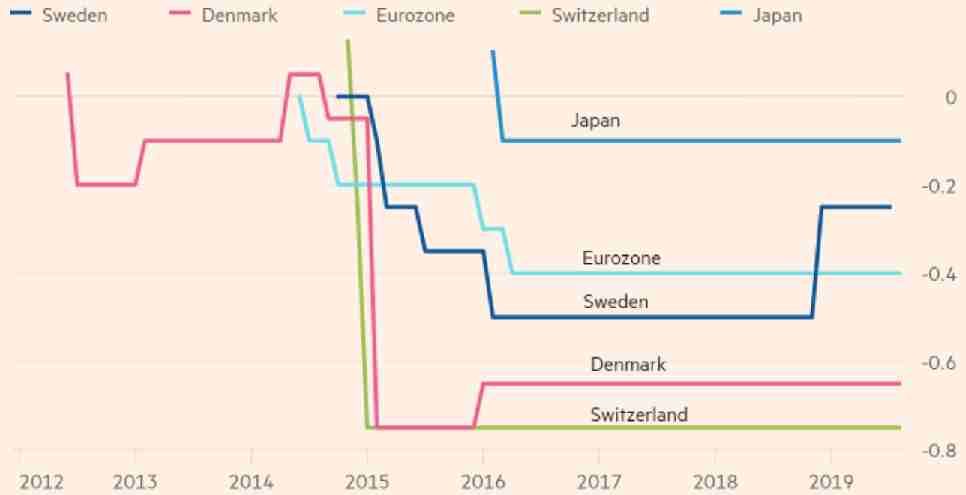

28.3 Put money in a bank account and get rich

My parents always told me: “Stop buying that many stamps. Better take your money to a bank and get rich from the deposit interest.” I doubt, however, if this strategy is valid in times when the ECB and some other central banks set negative key interest rates, see Figure 28.3. Negative interest rate policies were long considered unthinkable because economists believed in the so-called Zero Lower Bound (ZLB). This refers to the notion that a NIRP is ineffective because private banks cannot charge negative deposit rates; otherwise, people would withdraw their cash and keep it privately. As some have recently learned, there are indeed some banks that have charged negative interest rates on customer deposits without any bank runs.

Source: Refinitiv, FT

It must be noted, however, that commercial banks charge negative interest rates only on a small scale. Most banks charge negative interest rates only on part of the deposited assets, only for companies, or only for (short-term) assets above a certain amount. According to a survey of Verivox, as of June 7, 2022:

- 451 banks have published negative interest rates for retail customers on their websites or in their online price lists.

- 23 banks charge fees for the usually free overnight deposit accounts, creating a de facto negative interest rate.

- According to media reports, some banks and savings banks charge negative interest rates but do not publish them online.

28.4 European Central Bank

28.4.1 Objective

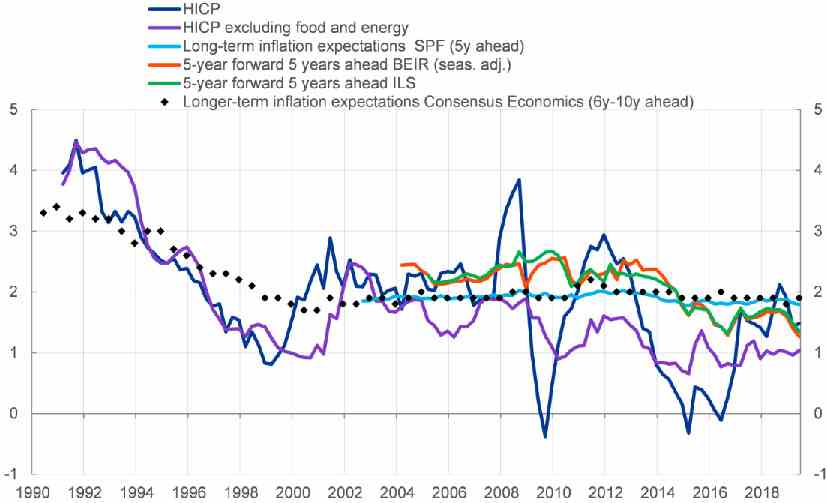

The primary objective of the European Central Bank (ECB) is to maintain price stability within the Eurozone, specifically an inflation rate of under 2%. In particular, the goal is to achieve “a year-on-year increase in the Harmonised Index of Consumer Prices (HICP) for the euro area of below 2%” (see: ECB). Moreover, the ECB “shall support the general economic policies in the Union” (see Article 127(1) TFEU).

In Figure 28.4, I present inflation rates and inflation expectations from 1990 onwards. The figure shows that the inflation rate has circulated more or less around 2%, despite the Eurozone experiencing serious economic turbulence over the last decades. Thus, we can say that the ECB has been successful in achieving its main objective.

28.4.2 Monetary policy instruments

In recent years, the ECB has deployed an innovative, multi-pronged approach in designing its policy stance. In summary, the current policy mix includes four elements: (i) pushing the policy rate into negative territory, (ii) forward guidance on the future policy path, (iii) the asset purchase programs, and (iv) the targeted longer-term refinancing operations (TLTROs). Importantly, these measures work as a package, with significant complementarities across the different instruments. However, we do not aim to discuss these instruments here. Instead, we focus on the most recognized instrument, that is, the central bank interest/policy rate (CBPR).

28.4.3 Central bank interest/policy rate (CBPR)

When people talk about the central bank interest/policy rate (CBPR), they usually refer to the deposit facility rate, which is one of the three interest rates the ECB sets every six weeks. This rate defines the interest banks receive for depositing money with the central bank overnight.

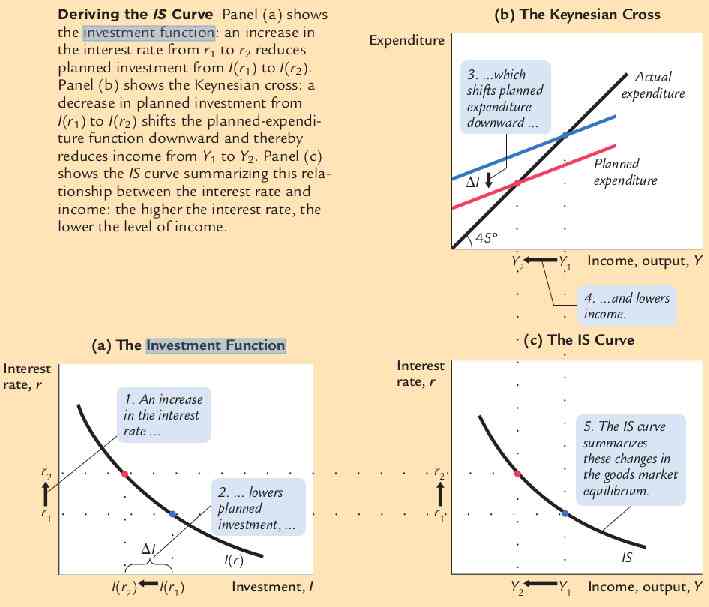

28.4.3.1 The textbook economics of the CBPR

All major introductory macroeconomic textbooks assume that investments increase when interest rates decrease, and vice versa. This investment function is illustrated in Figure 28.5. An increase in investments transmits into higher aggregate demand and output through the IS curve, as illustrated in macroeconomic textbooks. It doesn’t require a formal model to understand that higher aggregate demand and output yield higher prices.

Source: Mankiw (2010, p. 299)

However, most textbooks refrain from discussing how the investment function behaves when interest rates approach zero or even become negative. The reason is that NIRP was long considered unthinkable, as highlighted by a quote from Warren Buffet:

“What’s happened with interest rates is really extraordinary. I mean, you can go back and read everything, Keynes, Adam Smith, Ricardo, Galbraith, Paul Samuelson, or you name. You won’t see a word in my view anything I’ve ever seen about sustained negative interest rates. I mean, we are doing something the world hasn’t seen.” Warren Buffet in a CNBC interview, 2016.

Instead, the so-called Zero Lower Bound (ZLB) was dominant. It posits that a short-term nominal interest rate of zero causes a liquidity trap and limits the capacity of central banks to stimulate economic growth. The main argument is that it is difficult to encourage investors to deposit money at zero or negative interest rates. Thus, economist thought that central banks will not reduce interest rates below this bound. As already mentioned, they were wrong.

We should re-investigate the investment function. As NIRP exists, we should discuss whether NIRP is an effective tool for stimulating investments and increase prices.

Basically, four ways exist in which NIRP can increase investments:

- Banks can lend more to households and companies, rather than holding on to cash, which has now become costly.

- Businesses can invest more, as funding investments is now cheaper.

- Households could save less or borrow to spend more.

- Demand for the currency could fall, leading to a depreciation of the currency, an increase in the price of imported goods, and growing demand for the country’s exports, which are now cheaper for foreign buyers.

If we abstract from the fourth way, the effectiveness of NIRP hinges on whether the policy rates pass through to deposit and lending rates. In the next section, I will present the work of Eggertsson et al. (2017) to answer that question. This was one of the few studies available at the time of writing these notes, see Figure 28.6.

Source: investmentnews.com

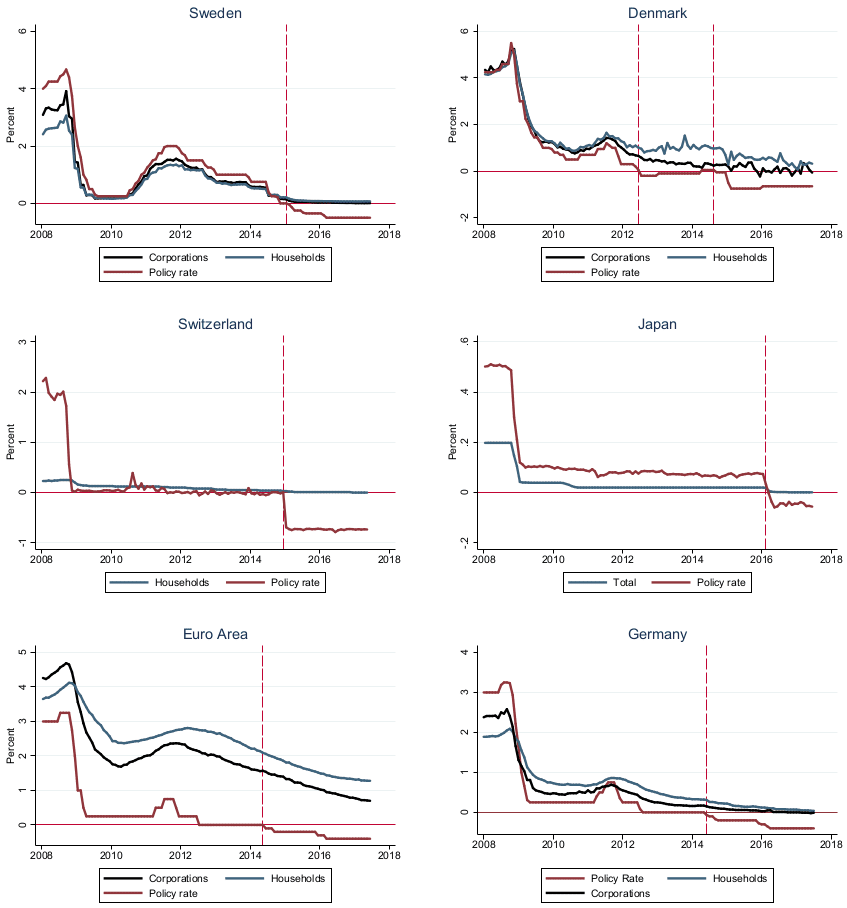

28.5 Limited pass-through to deposit rates

In Figure 28.7, I plot aggregate deposit rates for six economic areas where the policy rate is negative. The red vertical lines mark the month in which policy rates became negative. The Swedish central bank lowered its key policy rate below zero in February 2015. Deposit rates, which in Sweden are usually below the policy rate, did not follow the central bank rate into negative territory. Instead, deposit rates for both households and firms remain stuck at, or just above, zero. A similar picture emerges for Denmark, which crossed the ZLB twice. In both Sweden and Denmark, the negative policy rate has not been transmitted to deposit rates.

Source: Eggertsson et al. (2017)

The deposit rates in Switzerland and Japan were already very low for some time when the ZLB was crossed. However, even then the other rates did not follow the policy rate into negative territory.

The ECB hit the ZLB in June 2014. Aggregate deposit rates in the Euro Area are high and thus have more room to fall before reaching the zero lower bound. Moreover, the deposit rate does not normally follow the policy rate as closely as in other cases. One reason for this is the heterogeneity of the Euro Area. Focusing on Germany, a similar pattern emerges; that is, despite negative policy rates, the deposit rate appears bounded by zero.

Limited pass-through to deposit rates: Overall, the presented aggregate evidence indicates that the impact of policy rates on deposit rates was limited and strongly suggests a lower bound on deposit rates.

28.6 Limited pass-through to lending rates

In the relevant figure, I plot lending rates for the six economic areas with negative policy rates. While lending rates usually closely follow the policy rate, a disconnect appears once the policy rate breaks the ZLB. Lending rates in Sweden, Denmark, and Switzerland seem less sensitive to the respective policy rates once they become negative.

Source: Eggertsson et al. (2017)

The Euro Area is somewhat of an outlier, as lending rates have appeared to decrease. This is not surprising in light of the higher-than-zero deposit rates documented above. Again, in the case of Germany, where the zero lower bound on the deposit rate is binding, lending rates appear less responsive.

To further investigate the behavior of banks regarding lending rates, I present daily bank-level data for thirteen Swedish credit institutions. The analysis shows that while there is some initial reduction in lending rates, most rates increase again shortly thereafter when the policy rate is negative. This indicates that the total impact on lending rates seems limited. Moreover, there is substantial dispersion, with several banks maintaining their lending rates unchanged despite repeated interest rate reductions below zero.

Limited pass-through to lending rates: The impact of policy rates on lending rates seems limited once the ZLB has passed. Moreover, the dispersion of lending rates within territories increased when the policy rate turned negative, and some banks even increased (!) their lending rates when the policy rate was negative.

28.7 Does NIRP work?

Overall, there is a lack of research evaluating the empirical impact of NIRP. Considering the fact that NIRP is a relatively new phenomenon, this is not surprising. Additionally, the NIRP is hard to evaluate as there is no counterfactual, and the policy rate instrument is just one of many monetary instruments used by the ECB in recent years. Thus, it is difficult to establish an empirical identification strategy that allows for a sort of ceteris paribus interpretation.

The ECB faced heavy criticism for the NIRP. While I cannot list all points of skepticism, I would like to mention some reasonable ones here:

- Private banks cannot transmit negative interest rates to their customers. This reduces the profitability of private banks, which may subsequently raise lending rates to preserve their interest margin. We saw this in Sweden, where banks increased rates for mortgages and loans to maintain profitability. This undermines policy effectiveness.

- If lending rates become very low, more risky investments get financed, introducing economic uncertainties to the market.

- Finally, a NIRP may harm the reputation of the Euro as people may flee into other (financial) assets or alternative currencies like Bitcoin.