15 Externalities

An externality is an uncompensated impact of one economically active unit’s (person or firm) actions on the well-being of a bystander. It arises when a person engages in an activity that affects the well-being of a bystander and yet neither pays nor receives any compensation for that effect.

When the impact on the bystander is adverse, the externality is called a negative externality. When the impact on the bystander is beneficial, the externality is called a positive externality. Externalities cause markets to be inefficient and thus fail to maximize total surplus. Buyers/consumers and sellers/producers neglect the external effects of their actions. (Otherwise, the effects wouldn’t be considered to be external.)

15.1 Positive and negative externalities

Watch the video shown in Figure 15.1.

Source: Youtube

Example: Aluminum industry

Background: Aluminum factories emit pollution (a negative externality). For each unit of aluminum produced, a certain amount of smoke enters the atmosphere. The smoke poses a health risk for innocent bystanders who breathe the air.

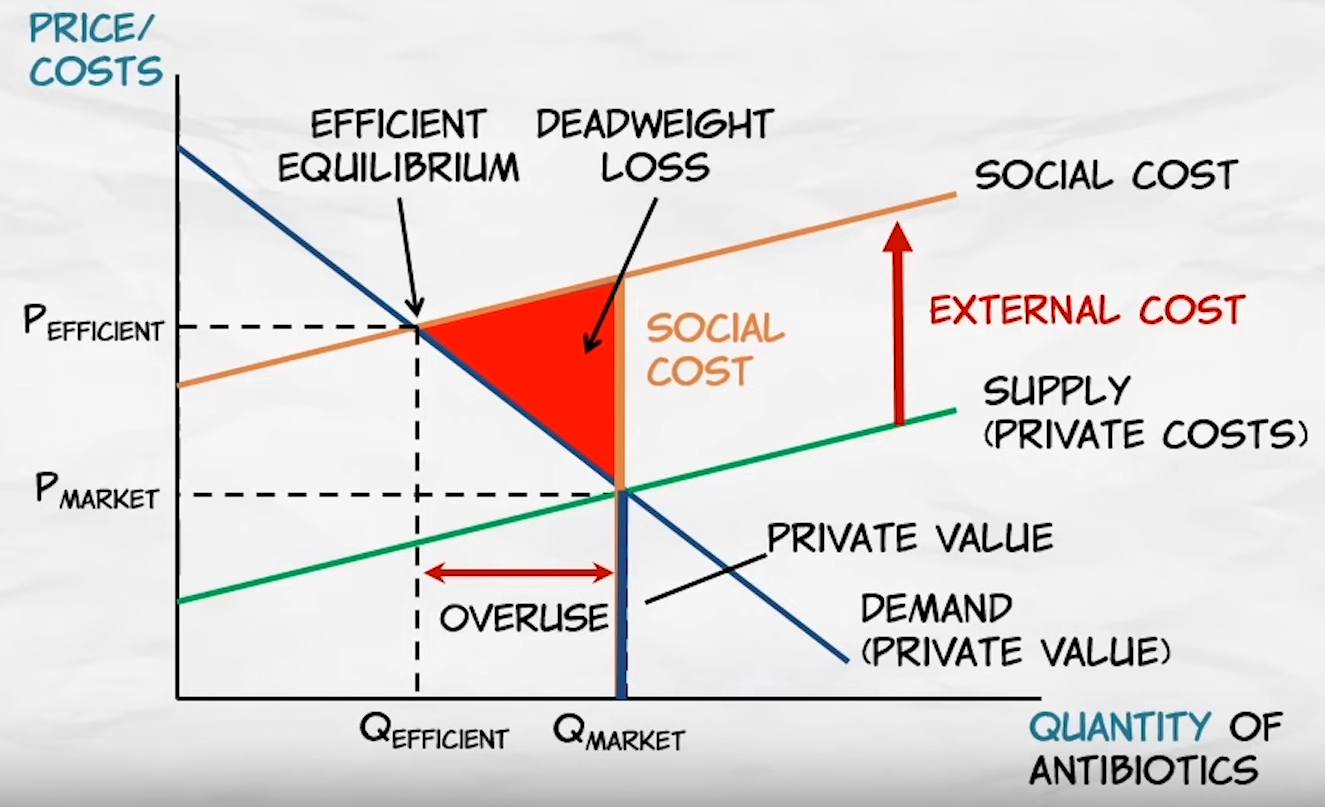

How does a negative externality affect the efficiency of the market outcome?

- The cost to society of producing aluminum is larger than the cost to the aluminum producers.

- The social cost includes the private costs of the aluminum producers plus the costs of the bystanders impacted by the pollution.

- The social-cost curve is above the supply curve (because it adds the external costs of aluminum production).

- The socially optimal equilibrium (intersection of social-cost curve and demand curve) is different from the actual equilibrium (where externalities are not considered).

One solution: Policymakers can tax aluminum producers for each ton of aluminum sold. The tax shifts the supply curve upward by the size of the tax. The tax should reflect the external cost of pollutants released into the atmosphere (in order to match the social-cost curve). The new market equilibrium would result in the socially optimal quantity of aluminum.

Another solution: Internalizing the externality: Altering incentives so that people and firms account for the external effects of their actions.

Alternatives: If property rights were clearly defined, we would have a (theoretical) chance of a market solution. However, the transaction costs are probably simply too high, as all people are harmed, necessitating that all people bargain with the polluting firms.

15.2 Production externalities

Production externalities refer to a side effect from an industrial operation, such as a paper mill producing waste that is dumped into a river. They are usually unintended, and their impacts are typically unrelated to and unsolicited by anyone. They can have economic, social, or environmental side effects. Production externalities can be measured in terms of the difference between the actual cost of production of the good and the real cost of this production to society at large. The impact of production externalities can be positive or negative or a combination of both.

Examples of production externalities:

- (+) The construction and operation of an airport will benefit local businesses because of increased accessibility.

- (+) An industrial company providing first aid classes for employees to increase workplace safety. This may also save lives outside the factory.

- (+) A foreign firm that demonstrates up-to-date technologies to local firms and improves their productivity.

- (+) Many sectors participate in technological innovation that happens in one sector (technological spillovers).

- (-) Noise pollution produced by a productive unit.

- (-) Increased usage of antibiotics propagates increased antibiotic-resistant infections.

- (-) The development of ill health, notably early-onset Type II diabetes and metabolic syndrome, as a result of companies over-processing foods including the addition of (too much) sugar.

15.3 Consumption externalities

Examples of consumption externalities:

- (+) Going to university. Your education benefits the rest of society (you can teach others).

- (+) Taking medicine or a vaccine which prevents the spread of infectious disease.

- (-) Consuming fireworks causes damage to the environment and to the health of other people.

- (-) Driving a car pollutes the environment and injures people.

- (-) Smoking and eating unhealthily may cause costs for other people.

15.4 Government interventions

Governments can manage externalities in two ways:

Command-and-control policies which regulate behavior directly. Regulations that require or forbid certain behaviors or subsidize good behavior. Example: Making it a crime to dump hazardous chemicals into the water supply.

Market-based policies which provide incentives so that firms can determine the best way to solve a problem.

Corrective tax: A tax designed to induce private decision-makers to take into account the social costs that arise from a negative externality.

Tradable permits (aka “Cap and Trade”): For example, voluntary transfer of the right to pollute from one firm to another. The government, in effect, creates a scarce resource (“pollution permits”). The result is the creation of a market governed by supply and demand. Permits end up in the hands of firms that value them most highly. Tradable green certificates of the EU are financial assets issued to producers of certified green electricity and can be regarded as a market-based environmental subsidy.

15.5 Private solutions to externalities

In some cases, government intervention is not necessarily needed to address externalities and to coordinate the behavior of market participants. For instance, if your neighbor plays loud music, you can talk to him and bargain for a good solution that leaves both parties better off.

Some types of private solutions include: - Moral codes and social sanctions. - Charitable and private organizations that aim to help and bring people together.

15.6 The Coase theorem

The Coase Theorem is named after Ronald Coase, a Nobel laureate of 1991 (see Figure 15.3). It states that if property rights exist and transaction costs are low, private transactions are efficient. In other words, with property rights and low transaction costs, there are no externalities. All costs and benefits are taken into account by the transacting parties. Thus, it doesn’t matter how the property rights are assigned as long as they are assigned. The theorem posits that if private parties can bargain without cost over the allocation of resources, they can solve the problem of externalities on their own. However, the theorem only works when the relevant parties can come to an agreement and are able to enforce that agreement. This is often not the case.

Transaction costs, in this respect, refer to the costs that parties incur during the process of agreeing to and following through on a bargain. Efficient bargaining becomes increasingly difficult when the number of interested parties is large. Coordinating more people is costly, and the more individuals involved, the less likely it is that private transactions yield a successful, efficient market outcome.

15.7 Imperfect information

In previous sections, we assumed that households and firms have perfect information on products and inputs. For example, to make good choices among goods and services available in the market, consumers must have full information on product quality, availability, and price. To make sound judgments about what inputs to use, producers must have full information on input availability, quality, and price. If this information is not available, consumers and producers are likely to make mistakes.

15.8 Moral hazard

An information problem that arises in insurance markets is moral hazard. Often, people enter into contracts in which the outcome of the contract depends on one of the parties’ future behavior. A moral hazard problem arises when one party to a contract passes the cost of his or her behavior onto the other party to the contract. In other words, moral hazard is a situation in which one party engages in risky behavior or fails to act in good faith because it knows the other party bears the economic consequences of their behavior.

15.9 Information asymmetry

When participants in an economic transaction have different information about the transaction, information is spread asymmetrically. This often causes inefficient markets. For example, in the healthcare market, there is a significant amount of information asymmetry, as doctors and suppliers of medical products and services possess much more knowledge on the topic and may use that informational advantage to offer overpriced and possibly unnecessary products and treatments.

15.10 Adverse selection

This sort of imperfect information occurs when a buyer or seller enters into an exchange with another party who has more information. For example, suppose there are two types of workers: lazy workers and hard workers. Each worker knows which they are, but employers cannot tell. If there is only one wage rate, lazy workers will be overpaid and hard workers will be underpaid relative to their productivity.

Another example is the secondhand car market. Suppose buyers cannot distinguish between a high-quality car (a cherry) and a low-quality car (a lemon), but sellers know the quality of their cars. Buyers would be willing to pay €6000 for a good car and €2000 for a bad car. If half of the cars for sale are good and half are bad, the market price of a car would be €4000.

Moreover, the asymmetric information yields a so-called adverse selection problem. That is, used car sellers know they are getting far more than their cars are worth by selling at €4000, while owners of good cars know they are getting far less than their cars are really worth. Thus, more lemon owners are attracted into selling their cars than are cherry owners. This sort of market is known as a market for lemons, named after the article The Market for Lemons: Quality Uncertainty and the Market Mechanism by George Akerlof (1970) (see Figure 15.4), the Nobel laureate of 2001.

15.11 Public goods (preliminary)

There are many goods that have no market price. These goods include things like nature (e.g., rivers, mountains, beaches, lakes) or government amenities and events (playgrounds, parks, parades). These goods face a different set of economic problems since the normal market forces that provide efficient allocation are absent.

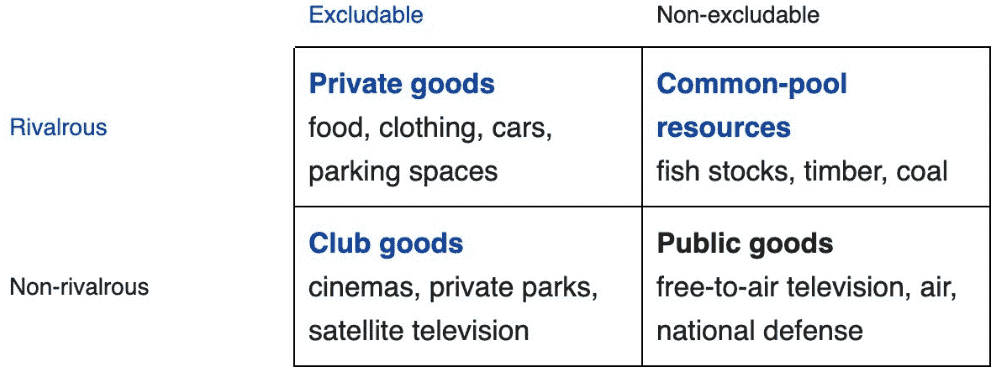

Economic goods can be grouped according to the following characteristics:

- Excludability: The property of a good whereby a person can be prevented from using it.

- Rivalry in consumption: The property of a good whereby one person’s use diminishes other people’s use.

Using the above characteristics, it is possible to categorize goods into four categories:

- Private goods: Goods that are both excludable and rival in consumption.

- Example: An ice cream cone. It is excludable because you can prevent someone from eating one. It is rival in consumption because if someone eats an ice cream cone, another person cannot eat the same cone.

- Public goods: Goods that are neither excludable nor rival in consumption.

- Example: A tornado siren in a small town. It is not excludable because it is impossible to prevent any single person from hearing it when the siren sounds. It is not rival in consumption because when one person benefits from the warning, it does not reduce the benefit to others. Other important public goods are national defense, basic research, and fighting poverty.

- Common resources: Goods that are rival in consumption but not excludable.

- Example: Fish in the ocean. It is rival in consumption because when one person catches a fish, there are fewer fish for the next person to catch. It is not excludable because it is difficult to stop fishermen from catching fish from a large ocean.

- Club goods: Goods that are excludable but not rival in consumption.

- Example: Fire protection in a small town. It is excludable because the fire department can decide not to save a building from a fire. It is not rival in consumption because once paid for, the additional cost of protecting one more house is small.

Whether governments should provide public goods or not must be the result of a cost-benefit analysis that compares the costs and benefits to society of providing a public good.

Common resources

- Common resources are not excludable (like public goods). Unlike public goods, common resources are rival in consumption: one person’s use degrades the resource for others.

- Tragedy of the Commons: A parable that illustrates why common resources are used more than is desirable from the standpoint of society as a whole.

- Social and private incentives differ.

- Government can solve the problem through regulation or taxes to reduce consumption.

- Government can also solve the problem by turning the common resource into a private good.

- Some important common resources:

- Clean air and water.

- Congested roads.

- Fish, whales, and other wildlife.

Switching between public and private goods

- Some goods switch between public and private goods depending on circumstances.

- Example: A fireworks display performed in a town can be a public good. A fireworks display at a private amusement park (e.g., Disneyland) is a private good.

- Example: A lighthouse operated by the government is a public good. A privately owned lighthouse that charges adjacent ports for operation is a private good.

The boundaries between goods are not always clear

- The characteristics of being excludable and rival in consumption can be a matter of degree.

- Example: Fish in an ocean may not be excludable because of practical challenges in managing ocean stocks. However, government restrictions and a large coast guard can make fish partially excludable.

- Public goods and common resources are closely related to externalities; both these goods and externalities result from something valuable having no associated price.

- Example: If an individual builds and operates a tornado siren in a town, the neighbors will benefit from the siren without paying for it (positive externality).

- Example: If an individual uses a common resource such as fish in the ocean, others are worse off because there are fewer fish to catch (negative externality).

- Private decisions about consumption and production can lead to an inefficient allocation of resources, and government intervention can potentially raise economic well-being.

15.12 The free-rider problem

- Example: A fireworks display. This good is not excludable (you cannot prevent someone from seeing fireworks) and it is not rival in consumption (because one person’s enjoyment does not reduce another’s enjoyment).

- Free rider: A person who receives the benefit of a good but avoids paying for it.

- The free-rider problem prevents the private market from supplying public goods.

- Government is one solution to this problem. If the total benefit exceeds the costs, a government can finance a public good with tax revenue.

15.13 The importance of property rights

- There are some goods that the market does not adequately address or provide for (clean air, for example).

- Governments are relied on to provide necessary common goods.

- Markets cannot allocate resources efficiently without property rights.

- Goods that do not have well-established owners lack similar incentives for firms and individual actors.

- Well-planned and necessary policies can make the allocation of resources more efficient and raise economic well-being.