4 Methods

Recommended reading: Mankiw (2024, ch. 2: Thinking Like an Economist), Huber (2025)

Learning outcomes:

Students will be able to:

- Understand the distinction between economic models and theories, recognizing their roles in analyzing economic problems,

- Apply scientific thinking in the construction of economic models, identifying and justifying the assumptions made in their development.

- Analyze positive statements, which can be tested through empirical observation, and normative statements, which reflect subjective opinions and values.

- Comprehend the reasons behind disagreements among economists, including differences in values and interpretations of positive theories.

- Appreciate the context in which economists operate, understanding that differing perspectives may arise from various interpretations of economic theory.

4.1 Theory and models

Economists utilize models and theories to analyze various problems. Distinguishing between these two concepts can be challenging, and practitioners often use the terms interchangeably.

A theory is a set of assumptions that aims to explain a particular phenomenon in nature. It must be possible to prove a theory true or false. In contrast, a model is a purposeful representation of reality. Models typically simplify the complexities of the real world by focusing only on the features that are relevant to the specific purpose at hand. Their goal is to reduce complexity, thereby facilitating a better understanding of the world. Furthermore, models assist in identifying key variables that can be empirically examined.

The art of scientific thinking and the construction of a theory or model lies in deciding which assumptions to make. Once we grasp the foundational model or theory, we can begin to relax or modify some of those assumptions.

For example, to understand how consumers make purchasing decisions, it may be helpful to start with the assumption that there are only two distinct goods and that the sole determinant of consumers’ decisions is price. When we test our model against real data, we will likely find that while price accounts for a significant portion of consumer behavior, it does not explain everything. We can then refine our theory to enhance the explanatory power of our model.

A model typically includes endogenous variables, whose values are determined within the model, and exogenous variables, whose values are set externally by the researcher.

In the words of Nobel laureate Robert Solow:

“All theory depends on assumptions which are not quite true. That is what makes it theory. The art of successful theorizing is to make the inevitable simplifying assumptions in such a way that the final results are not very sensitive.”

— Robert M. Solow (1956, p. 65)

4.2 A didactical note on models

In these note, I introduce some mathematical economic models. I strongly believe that these models are useful for thinking about economics in a structured way. Familiarity with them will enable you to engage with contemporary textbooks and literature. The models including their formulas and their graphical visualizations, can assist in understanding, analyzing, and memorizing the more complex facets of economics.

Economic models are built on transparent assumptions. Often these assumptions are formulated in a set of equations. A good model should provide valuable insights into how rational agents behave and how the economy functions. Unfortunately, students often feel overwhelmed by these models, as the application of mathematics and hence rigorous logical thinking is sort of new to them. I frequently hear that there are simpler ways to convey the argument. While there may be some truth to this, I firmly believe that formally introducing international economics is the most effective approach in the medium and long term. Allow me to justify my conviction:

The narrative method, such as telling stories and listing bullet points, efficiently informs about different topics but also has its drawbacks. Students can easily get lost in intuitive anecdotes without learning to think critically or identify underlying driving forces. They often cram the presented information only for exams and forget it shortly afterward.

Compared to anecdotes, formal models are not necessarily true, yet they provide deeper insights into topics than anecdotal storytelling.

A formal model is usually more flexible than stories or anecdotes. Once students grasp the underlying logic of a model and can interpret and evaluate its meaning, they can apply their findings to various circumstances or problems. In contrast, an anecdote is merely a story that offers a limited perspective. Drawing general conclusions and analogies from anecdotal evidence is problematic.

A mathematical economic model represents a proof of an argument, precisely stating the assumptions under which the argument holds true. In a narrative, the underlying assumptions and premises of an argument are often obscured.

Formal reasoning is the standard in economic research. By understanding the basic concepts, students can read and comprehend current literature, allowing them to conduct research and solve problems in their professional lives.

Once students understand an economic model, they grasp the underlying relationships, making it less likely for them to forget. In other words, a formal model ensures that students are not merely repeating the teacher’s words but are capable of thinking and reasoning independently.

4.3 Feynman on scientific method

Richard P. Feynman was an American theoretical physicist. At the age of 25, he became a group leader of the Manhattan Project in Los Alamos, received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1965, authored one of the most famous science books of our time (Surely You’re Joking, Mr. Feynman!) (Feynman, 1985), and remains a hero for many enthusiasts, educators, and nerds (see Figure 4.1). In 1964, more than half a century ago, he gave a good description of scientific method which is still worth considering.

Watch the video Feynman on scientific method:

Source: Youtube

Here is a transcript of his lecture:

“Now, I’m going to discuss how we would look for a new law. In general, we look for a new law by the following process. First, we guess it.

Then we—well, don’t laugh. That’s really true. Then we compute the consequences of the guess to see if this law that we guessed is right. We check what it would imply and compare those computed results to nature. Or we compare it to experiments or experiences, comparing it directly with observations to see if it works.

If it disagrees with experiment, it’s wrong. And that simple statement is the key to science. It doesn’t matter how beautiful your guess is. It doesn’t matter how smart you are, who made the guess, or what his name is; if it disagrees with experiment, it’s wrong. That’s all there is to it.

It’s therefore not unscientific to take a guess, although many people outside of science think it is. For instance, I had a conversation about flying saucers a few years ago with laymen.

Because I’m a scientist, I said, ‘I don’t think there are flying saucers.’ Then my antagonist said, ‘Is it impossible that there are flying saucers? Can you prove that it’s impossible?’ I said, ‘No, I can’t prove it’s impossible. It’s just very unlikely.’

They replied, ‘You are very unscientific. If you can’t prove something is impossible, then how can you say it’s unlikely?’ Well, that’s how science works. It’s scientific to say what’s more likely or less likely, rather than attempting to prove every possibility and impossibility.

To clarify, I concluded by saying, ’From my understanding of the world around me, I believe it’s much more likely that the reports of flying saucers are the result of the known irrational characteristics of terrestrial intelligence rather than the unknown rational efforts of extraterrestrial intelligence. It’s just more likely, that’s all. And it’s a good guess. We always try to guess the most likely explanation, keeping in the back of our minds that if it doesn’t work, we must consider other possibilities.

[…]

Now, you see, of course, that with this method, we can disprove any specific theory. We can have a definite theory or a real guess from which we can compute consequences that could be compared to experiments, and in principle, we can discard any theory. You can always prove any definite theory wrong. Notice, however, we never prove it right.

Suppose you invent a good guess, calculate the consequences, and find that every consequence matches the experiments. Does that mean your theory is right? No, it simply has not been proved wrong. Because in the future, there could be a wider range of experiments, and you may compute a broader range of consequences that could reveal that your theory is actually incorrect.

That’s why laws, like Newton’s laws of motion for planets, have lasted for such a long time. He guessed the law of gravitation, calculated various consequences for the solar system, and it took several hundred years before the slight error in the motion of Mercury was discovered.

[…]

I must also point out that you cannot prove a vague theory wrong. If the guess you make is poorly expressed and rather vague, and if the method you use to compute the consequences is also vague—you aren’t sure. You might say, ‘I think everything is due to [INAUDIBLE], and [INAUDIBLE] does this and that,’ more or less. Thus, you can explain how this works. However, that theory is considered ‘good’ because it cannot be proved wrong.

If the process for computing the consequences is indefinite, then with a little skill, any experimental result can be made to fit—at least in theory. You’re probably familiar with that in other fields. For example, A hates his mother. The reason is, of course, that she didn’t show him enough love or care when he was a child. However, upon investigation, you may find that she actually loved him very much and everything was fine. Then the explanation changes to say she was overindulgent when he was [INAUDIBLE]. With a vague theory, it’s possible to arrive at either conclusion.

[APPLAUSE]

Now, wait. The cure for this is the following: it would be possible to specify ahead of time how much love is insufficient and how much constitutes overindulgence precisely, enabling a legitimate theory against which you can conduct tests. It’s often said that when this is pointed out regarding how much love is involved, you’re dealing with psychological matters, and such things can’t be defined so precisely. Yes, but then you can’t claim to know anything about it. [APPLAUSE]

Now, I want to concentrate for now on—because I’m a theoretical physicist and more fascinated with this end of the problem—how you make guesses. It is irrelevant where the guess originates. What matters is that it agrees with experiments and is as precise as possible.

But, you might say, that’s very simple. We just set up a machine—a great computing machine—with a random wheel that makes a succession of guesses. Each time it guesses hypotheses about how nature should work, it computes the consequences and compares them to a list of experimental results at the other end. In other words, guessing is a task for simpletons.

Actually, it’s quite the opposite, and I will try to explain why. […]

4.4 The economic way of doing research

Economics is a social science. When economists are trying to …

- …change the world, they act as policy advisors.

- …explain the world, they are scientists.

Economists distinguish between two types of statements:

A positive statement attempts to describe the world as it is and can be tested by checking it against facts. In other words, a positive statement deals with assumptions about the state of the world and some conclusions. The validity of the statement is verifiable or testable in principle, no matter how difficult it might be.

A normative statement claims how the world should be and cannot be tested. Normative statements often contain words such as have to, ought to, must, should, or non-quantifiable adjectives like important, which cannot be objectively measured. Consequently, normative statements cannot be verified or falsified by scientific methods.

The task of economic science is to discover positive statements that align with our observations of the world and enable us to understand how the economic world operates. This task is substantial and can be broken into three steps:

- Observation and measurement: Economists observe and measure economic activity, tracking data such as quantities of resources, wages and work hours, prices and quantities of goods and services produced, taxes and government spending, and the volume and price of traded goods.

- Model building

- Testing models

Research methodologies in economics often blend the inductive and deductive approaches. Inductive reasoning builds theories, while deductive reasoning tests existing ones. It’s a methodical interplay between creation and scrutiny in the realm of economic research.

When scientists want to act as political advisors, they are often asked to make normative statements. From an ethical point of view, however, it is difficult to make normative statements without including subjective judgments, which can make such statements unscientific. Therefore, scientists should rely on moral criteria to justify their judgments and normative statements.

Among these criteria, the Pareto criterion is one of the best known and most widely used. It states that only changes that benefit at least one individual without harming others can be considered improvements. This concept is often used in economics to discuss the distribution of resources, welfare economics and policy making.

4.5 Cause and effect

Economists seek to unscramble cause and effect. They are particularly interested in positive statements concerning causal relationships. For example, are computers becoming cheaper because people are purchasing them in greater quantities, or are consumers buying more computers because prices are falling? Alternatively, could a third factor be influencing both the price of computers and the quantity sold? To address these questions, economists develop and test economic and econometric models.

Unfortunately, conducting experiments can be challenging for economists, and most economic behaviors are influenced by multiple simultaneous factors. To isolate the effect of interest, they employ various logical and econometric tools, including the ceteris paribus assumption, which means other things being equal. This approach enables economists to delineate cause-and-effect relationships by varying only one variable at a time while keeping all other relevant factors constant.

4.6 Common causal and predictive fallacies

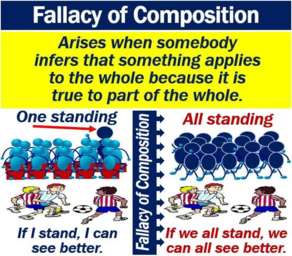

- The fallacy of composition asserts that what is true for the parts is true for the whole, or vice versa.

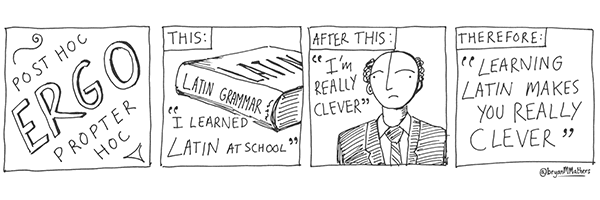

- The post hoc fallacy is the error of reasoning that a first event causes a second event merely because the first occurs before the second.

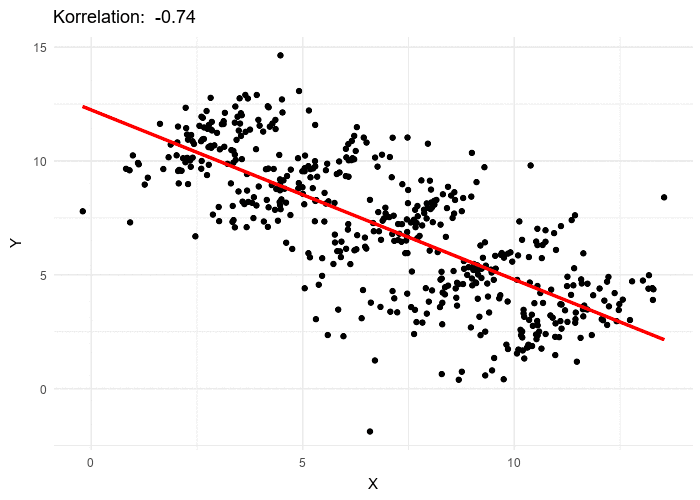

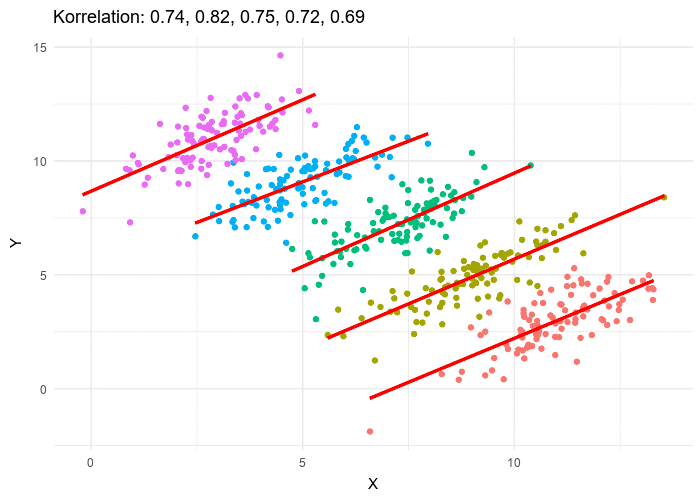

- Simpson’s Paradox is a phenomenon in probability and statistics where a trend appears in several groups of data but disappears or reverses when the groups are combined.

- Correlation does not imply causation.

Correlation refers to a statistical relationship between two variables, where one variable tends to increase or decrease as the other variable also increases or decreases. However, just because two variables are correlated does not necessarily mean that one variable causes the other. This is known as the correlation does not imply causation principle.

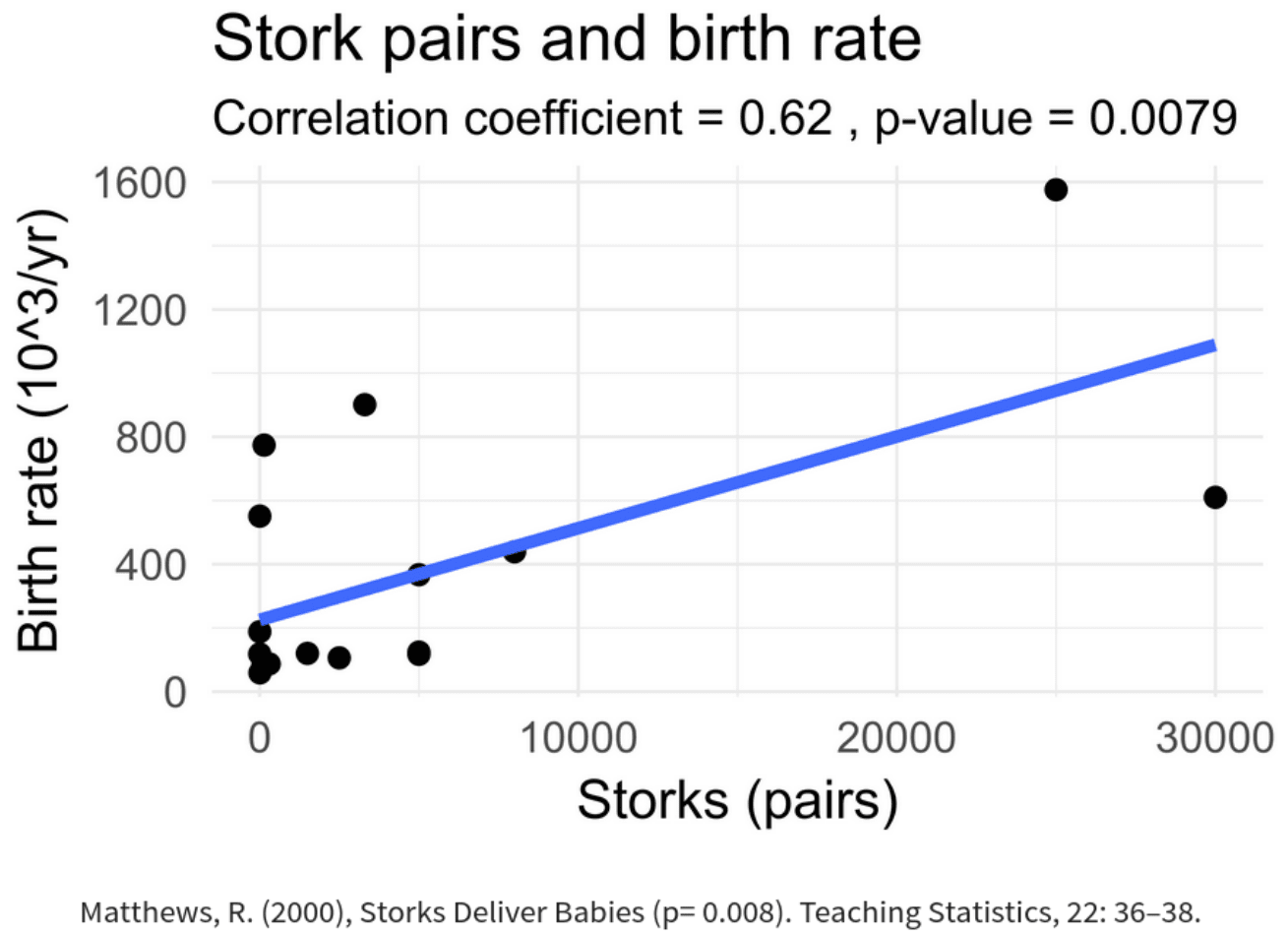

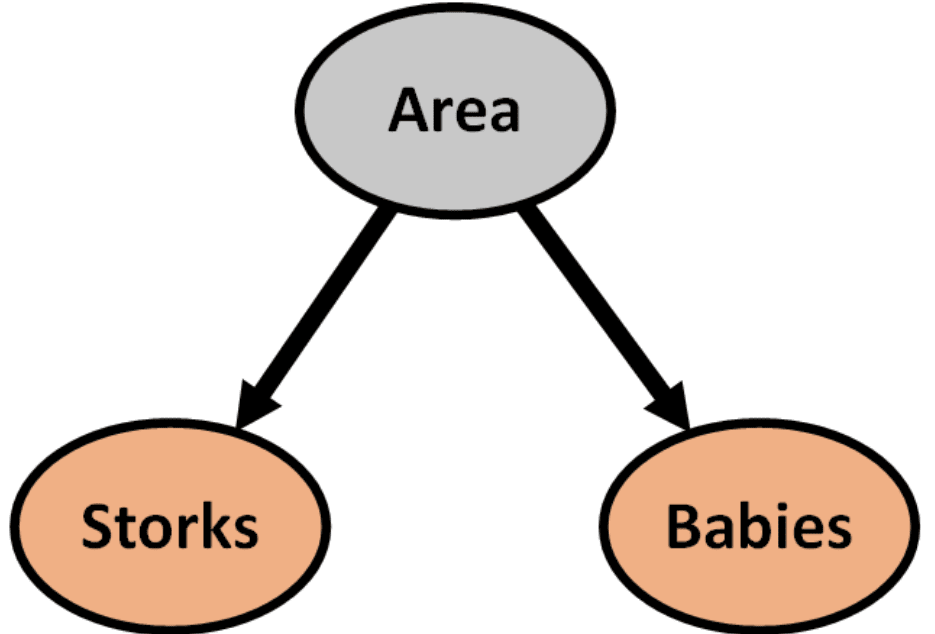

For example, across many areas the number of storks is correlated with the birth rate of babies (see Matthews (2000) and Figure 4.6). However, this does not mean that the presence of storks causes an increase in the birth rate. It is possible that both the number of storks and the number of babies born are influenced by other factors, such as the overall population density or economic conditions in the area.

Therefore, it is important to carefully consider all possible explanations (confounders) for a correlation and to use data to disentangle the true cause-and-effect relationship between variables.

4.7 Why economists disagree

Economists are often accused of contradicting each other. Contrary to popular belief, they find much common ground on a wide range of issues. Nevertheless, economists may:

- Disagree about the validity of alternative positive theories regarding how the world works.

- Have different values and, therefore, differing normative views about which policies should be implemented.

“As a new graduate student, you are at the beginning of a new stage of your life. In a few months, you will be overloaded with definitions, concepts, and models. Your teachers will guide you into the wonders of economics and will rarely have time to pause and raise fundamental questions about what these models are supposed to mean. It is not unlikely that you will be brainwashed by the professional-sounding language and hidden assumptions. I am afraid I am about to initiate you into this inevitable process. Still, I want to take this opportunity to pause for a moment and alert you to the fact that many economists have strong and conflicting views about what economic theory is. Some see it as a set of theories that can (or should) be tested. Others view it as a set of tools for economic agents, while yet others perceive it as a framework through which professional and academic economists interpret the world.” (Rubinstein, 2006, p. ix)